(Press-News.org) UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 00:01 GMT MONDAY 28 OCTOBER / 20:01 ET SUNDAY 27 OCTOBER 2024

More social species live longer, Oxford study finds

New research published today (28 Oct) from the University of Oxford has revealed that species that are more social live longer and produce offspring for a greater timespan. This is the first study on this topic which spans the animal kingdom, from jellyfish to humans.

What are the benefits and costs of sociality? Social organisms may enjoy benefits such as sharing resources, being better protected from predators, and having support to raise offspring. However, by living in more tightly packed groups, social organisms may also suffer disadvantages such as the spread of disease, increased competition, aggression, and conflict.

A new study led by the University of Oxford has carried out a comprehensive assessment on the link between sociality and different life history traits such as generation time, life expectancy, and the length of their reproductive window. Up to now, research evaluating the overall impacts of sociality on performance has focused on single species or groups, such as birds or some mammals. The new study assessed 152 animal species from a wide variety of taxonomic groups, including birds, mammals, insects, and corals.

The results of the study showed that more social species live longer, postpone maturity, and are more likely to reproduce successfully than more solitary species. While social species may not be the best to adapt and benefit from a rapidly changing environment, they are often more resilient as a group. This novel finding supports the hypotheses that, even though sociality comes with some obvious costs, the overall benefits are greater.

The study also revealed that sociality does influence the reduction in an animal’s ability to reproduce or survive as they age, known as senescence. For example, social allies may help protect against predation, increasing lifespan, but the stress of social hierarchies and conflicts can have the opposite effect.

Lead author Associate Professor Rob Salguero-Gómez (Department of Biology, University of Oxford) said: “Sociality is a fundamental aspect of many animals. However, we still lack cross-taxonomic evidence of the fitness costs and benefits of being social. Here, by using an unprecedented number of animal species this work has demonstrated that species that are more social (most monkeys, humans, elephants, flamingos, and parrots) display longer life spans and reproductive windows than more solitary species (some fish, reptiles, and some insects)."

Whereas previous studies have tended to class sociality as a binary category (i.e. a species is either not social, or social), this new study recognised that sociality exists as a spectrum across animal species.* The continuum used included more ‘intermediate’ ways of sociality, such as being gregarious (e.g., wildebeests, zebras, flock-forming birds), communal (e.g., purple martin birds), or colonial (e.g., nesting birds, some wasps, coral polyps). The data were accessed via the open access COMADRE Animal Matrix Database (www.compadre-db.org), which is curated by his Associate Professor Salguero-Gómez’s research group at the University of Oxford.

Associate Professor Salguero-Gómez added: “In a post-COVID era, where the impacts of isolation have been quite tangible to humans (a highly social species), the research demonstrates that, across a comparative lens, being more social is associated with some tangible benefits."

Further research is ongoing in Associate Professor Salguero-Gómez’s research group to expand the database and combine the data with lab work and further modelling to estimate how more social populations buffer (or fail to) against climate change.

Notes to editors

Interviews with Associate Professor Rob Salguero-Gómez are available on request: rob.salguero-gomez@biology.ox.ac.uk

The paper ‘More social species live longer, have longer generation times and longer reproductive windows’ will be published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B at 00:01 GMT, Monday 28 October/ 00:01 ET Sunday 27 October 2024. It will be available online when the embargo lifts at: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/toc/rstb/2024/379/1916 To view a copy of the paper under embargo, contact Associate Professor Rob Salguero-Gómez: rob.salguero-gomez@biology.ox.ac.uk

Additional details

*Sociality was classified following the proposed continuum which shows that sociality is not binary:

solitary: individuals spend their time alone, except to breed e.g. tigers

gregarious: individuals spend time in groups but social interactions are loose e.g. wildebeests

communal: individuals live in close proximity and often share a common nesting or dwelling area, but do not engage in cooperative breeding e.g. purple martin

colonial: individuals live in close proximity and always share a common nesting or living area e.g. nesting birds

social: individuals live in close proximity and form stable, organised groups, engaging in social behaviours such as cooperative breeding and hierarchical structures e.g. elephants

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the ninth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

The Department of Biology is a University of Oxford department within the Maths, Physical, and Life Sciences Division. It utilises academic strength in a broad range of bioscience disciplines to tackle global challenges such as food security, biodiversity loss, climate change and global pandemics. It also helps to train and equip the biologists of the future through holistic undergraduate and graduate courses. For more information visit www.biology.ox.ac.uk.

END

More social species live longer, Oxford study finds

2024-10-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Magicians don’t mind sharing the secrets behind tricks – if they are their own

2024-10-27

Magic is one of the oldest forms of entertainment, and much of its enchantment is said to rely on the audience not knowing how the tricks are done.

However, while magicians swear to keep their secrets forever when they embark on their profession they are happy to share the tricks of their trade in certain circumstances, a new study shows.

Illusionists who took part in major new research thought it was OK to expose their own techniques, but not those invented by others, and also believe it is acceptable to reveal the secrets behind tricks invented by someone who has since died.

They didn’t think it was right to share the workings of a magic trick just to gain public ...

No incentive for older birds to make new friends

2024-10-27

Like people, birds have fewer friends as they age, but the reasons why are unclear. New research suggests they may just have no drive to.

In humans, it’s often been assumed that older people have fewer friends because they’re pickier about who they spend their time with. There’s also the issue that there are fewer people of their own age around.

But it’s hard to pick apart the various potential causes for humans, so researchers have turned to animals. The team behind the new research, led by Imperial College London, studied an isolated population of sparrows on the island of Lundy, in the Bristol Channel.

By mapping the ...

Development and validation of a new prognostic model for predicting survival outcomes in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure

2024-10-27

Background and Aims

Early determination of prognosis in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is crucial for optimizing treatment options and liver allocation. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with ACLF and to develop new prognostic models that accurately predict patient outcomes.

Methods

We retrospectively selected 1,952 hospitalized patients diagnosed with ACLF between January 2010 and June 2018. This cohort was used to develop new prognostic scores, which were subsequently validated in external groups.

Results

The study included 1,386 ACLF patients and identified six independent ...

Identification and validation of the Hsa_circ_0001726/miR-140-3p/KRAS axis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on microarray analyses and experiments

2024-10-27

Background and Aims

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most fatal malignancies. Epigenetic mechanisms have revealed that noncoding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs), are involved in HCC progression. This study aimed to construct a circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in HCC and validate one axis within the network.

Methods

HCC-related transcriptome data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus, and HCC-related genes were sourced from GeneCards to identify differentially expressed circRNAs and miRNAs. ...

New study warns that melting Arctic sea-ice could affect global ocean circulation

2024-10-27

“Our finding that enhanced melting of Arctic sea-ice likely resulted in significant cooling in northern Europe in the earth’s past is alarming,” says Mohamed Ezat from the iC3 Polar Research Hub, lead author of the new study. “This reminds us that the planet’s climate is a delicate balance, easily disrupted by changes in temperature and ice cover.”

Ice-free summer conditions are expected to occur in the Arctic Ocean from the year 2050 onwards.

Earlier this ...

Researchers test imlifidase enzyme versus plasma exchange in removing donor-specific antibodies in kidney transplant rejection trial

2024-10-27

San Diego, CA (October 26, 2024) — For kidney transplant recipients experiencing antibody-mediated rejection, the current standard of care involves removing donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) through plasmapheresis (PLEX)—a procedure that removes antibodies from the plasma portion of the blood. Results from a recent clinical trial reveal that an investigational drug called imlifidase, which cleaves and inactivates the type of antibodies that include DSAs, is more effective than PLEX. The research will be presented at ASN Kidney ...

Preclinical studies test novel gene therapy for treating IgA nephropathy

2024-10-26

San Diego, CA (October 26, 2024) — IgA nephropathy is an autoimmune kidney disease, and complement, a component of the innate immune system, plays a role in the condition’s pathogenesis. Investigators have developed and tested a novel gene therapy that enters kidney cells and enables them to block complement activation. The research will be presented at ASN Kidney Week 2024 October 23– 27.

The gene therapy, called PS-002, uses a modified virus to treat kidney cells called podocytes. Administration of PS-002 in a mouse model of IgA nephropathy reduced signs of kidney dysfunction, lowered complement ...

Trial assesses antibody therapy for chronic active antibody-mediated kidney transplant rejection

2024-10-26

San Diego, CA (October 26, 2024) — Chronic active antibody-mediated rejection (caAMR) is a common cause of allograft loss after transplantation, with no approved therapies. Clazakizumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6), stabilized kidney transplant recipients’ kidney function in a phase 2 trial. Investigators now have data from a phase 3 trial with clazakizumab. The findings from the Phase 3 IMAGINE trial, the largest placebo-controlled study in kidney transplant recipients with caAMR, will be ...

High-impact clinical trials generate promising results for improving kidney health: Part 2

2024-10-26

The results of numerous high-impact phase 3 clinical trials that could affect kidney-related medical care will be presented in-person at ASN Kidney Week 2024 October 23–27.

Hyponatremia, or a chronically low blood salt level, is the most common electrolyte disorder in hospitalized patients, and is associated with higher risks of death and re-hospitalization. In a recent trial, 2,173 hospitalized patients with hyponatremia from 9 centers across Europe were assigned to undergo either targeted correction of blood salt levels according to guidelines or to receive routine care for hyponatremia. The primary outcome was the combined ...

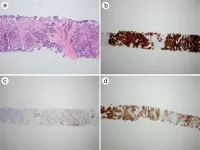

Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX as a novel diagnostic marker for differentiating pleural mesothelioma from non-small cell lung carcinoma

2024-10-26

Background and objectives

Mesothelioma is an aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis. Histological diagnosis of mesothelioma using limited tissue samples can be challenging. Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) is a transmembrane protein that is overexpressed in a variety of solid tumors. This study aimed to investigate the clinical utility of CAIX expression in the differential diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma from non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).

Methods

Unstained tissue microarray slides composed of 56 cases of pleural mesothelioma and 82 cases of NSCLC were subjected to immunohistochemical staining using a mouse anti-human antibody against CAIX.

Results

Of the 38 epithelioid mesothelioma ...