(Press-News.org) When light conditions rapidly change, our eyes have to respond to this change in fractions of a second to maintain stable visual processing. This is necessary when, for example, we drive through a forest and thus move through alternating stretches of shadows and clear sunlight. "In situations like these, it is not enough for the photoreceptors to adapt, but an additional corrective mechanism is required," said Professor Marion Silies of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). "Earlier work undertaken by her research group had already demonstrated that such a corrective 'gain control' mechanism exists in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, where it acts directly downstream of the photoreceptors. Silies' team has now managed to identify the algorithms, mechanisms, and neuronal networks that enable the fly to sustain stable visual processing when light levels change rapidly. The corresponding article has been published recently in Nature Communications.

Rapid changes in luminance challenge stable visual processing

Our vision needs to function accurately in many different situations – when we move in our surroundings as well as when our eyes follow an object that moves from light into shade. This applies to us humans and to many thousand animal species that rely heavily on vision to navigate. Rapid changes in luminance are also a problem in the world of inanimate objects when it comes to information processing by, for example, camera-based navigation systems. Hence, many self-driving cars depend on additional radar- or lidar-based technology to properly compute the contrast of an object relative to its background. "Animals are capable of doing this without such technology. Therefore, we decided to see what we could learn from animals about how visual information is stably processed under constantly changing lighting conditions," explained Marion Silies the research question.

Combination of theoretical and experimental approaches

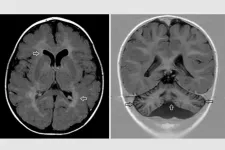

The compound eye of Drosophila melanogaster consists of 800 individual units or ommatidia. The contrast between an object and its background is determined postsynaptic of the photoreceptors. However, if luminance conditions suddenly change, as in the case of an object moving into the shadow of a tree, there will be differences in contrast responses. Without gain control, this would have consequences for all subsequent stages of visual processing, resulting in the object appearing different. The recent study with lead author Dr. Burak Gür used two-photon microscopy to describe where in visual circuitry stable contrast responses were first generated. This led to the identification of neuronal cell types that are positioned two synapses behind the photoreceptors.

These cell types respond only very locally to visual information. For the background luminance to be correctly included in computing contrast, this information needs narrow spatial pooling, as revealed by a computational model implemented by co-author Dr. Luisa Ramirez. "We started with a theoretical approach that predicted an optimal radius in images of natural environments to capture the background luminance across a particular region in visual space while, in parallel, we were searching for a cell type that had the functional properties to achieve this," said Marion Silies, head of the Neural Circuits lab at the JGU Institute of Developmental Biology and Neurobiology (IDN).

Information on luminance is spatially pooled

The Mainz-based team of neuroscientists has identified a cell type that meets all required criteria. These cells, designated Dm12, pool luminance signals over a specific radius, which in turn corrects the contrast response between the object and its background in rapidly changing light conditions. "We have discovered the algorithms, circuits, and molecular mechanisms that stabilize vision even when rapid luminance changes occur," summarized Silies, who has been investigating the visual system of the fruit fly over the past 15 years. She predicts that luminance gain control in mammals, including humans, is implemented in a similar manner, particularly as the necessary neuronal substrate is available.

The work for the research paper "Neural pathways and computations that achieve stable contrast processing tuned to natural scenes" was supported by an ERC Starting Grant awarded to Professor Marion Silies as well as funds of the Collaborative Research Center 1080 on Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neural Homeostasis and of the Research Unit 5289, RobustCircuit, both financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Related links:

https://ncl-idn.biologie.uni-mainz.de/ – Neural Circuits Lab at the JGU Institute of Developmental Biology and Neurobiology

https://idn.biologie.uni-mainz.de/ – Institute of Developmental Biology and Neurobiology (IDN) at the JGU Faculty of Biology

https://www.blogs.uni-mainz.de/fb10-biologie-eng/ – Faculty of Biology at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

https://robustcircuit.flygen.org/ – Research Unit 5289 "From Imprecision to Robustness in Neural Circuit Assembly" (RobustCircuit), funded by the German Research Foundation

https://www.crc1080.com/ – Collaborative Research Center 1080 "Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms in Neural Homeostasis", funded by the German Research Foundation

:

https://press.uni-mainz.de/neurons-in-the-visual-system-of-flies-exhibit-surprisingly-heterogeneous-wiring/ – press release "Neurons in the visual system of flies exhibit surprisingly heterogeneous wiring" (3 June 2024)

https://press.uni-mainz.de/franco-german-research-funding-in-the-field-of-biology/ – press release "Franco-German research funding in the field of biology" (8 Jan. 2024)

https://press.uni-mainz.de/local-motion-detectors-in-fruit-flies-sense-complex-patterns-generated-by-their-own-motion/ – press release "Local motion detectors in fruit flies sense complex patterns generated by their own motion" (5 Apr. 2022)

https://press.uni-mainz.de/marion-silies-receives-erc-consolidator-grant-for-research-on-adaptive-functions-of-visual-systems/ – press release "Marion Silies receives ERC Consolidator Grant for research on adaptive functions of visual systems" (4 Apr. 2022)

https://press.uni-mainz.de/fruit-flies-respond-to-rapid-changes-in-the-visual-environment-thanks-to-luminance-sensitive-lamina-neurons/ – press release "Fruit flies respond to rapid changes in the visual environment thanks to luminance-sensitive lamina neurons" (5 Feb. 2020)

https://www.magazine.uni-mainz.de/how-flies-and-humans-see-the-world/ – JGU Magazine: "How flies and humans see the world" (14 Jan. 2020) END

How fruit flies achieve accurate visual behavior despite changing light conditions

Researchers identify neuronal networks and mechanisms that show how contrasts can be rapidly and reliably perceived even when light levels vary

2024-10-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

First blueprint of the human spliceosome revealed

2024-10-31

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona have created the first blueprint of the human spliceosome, the most complex and intricate molecular machine inside every cell. The scientific feat, which took more than a decade to complete, is published today in the journal Science.

The spliceosome edits genetic messages transcribed from DNA, allowing cells to create different versions of a protein from a single gene. The vast majority of human genes – more than nine in ten – are edited by the spliceosome. Errors in the process are linked to a wide spectrum of diseases including most types of cancer, neurodegenerative conditions and genetic ...

The harmful frequency and reach of unhealthy foods on social media

2024-10-31

An analysis of social media posts that mention food and beverage products finds that fast food restaurants and sugar sweetened beverages are the most common, with millions of posts reaching billions of users over the course of a year. The study, published in the open access journal PLOS Digital Health, highlights the sheer volume of content normalising unhealthy eating, and argues that policies are needed to protect young people in the digital food environment.

Obesity is a health challenge around the world and food environments, including in the digital space, can influence ...

Autistic traits shape how we explore

2024-10-31

People with stronger autistic trails showed distinct exploration patterns and higher levels of persistence in a computer game, ultimately resulting in better performance than people with lower scores of autistic traits, according to a new study published this week in PLOS Computational Biology by Francesco Poli of Radboud Universiteit, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Scientists know that individuals display curiosity and explore their environments to learn. How a person selects what they want to explore plays a pivotal role in how they learn and research has shown that exploration levels are highly variable across ...

UCLA chemists just broke a 100-year-old rule and say it’s time to rewrite the textbooks

2024-10-31

Key takeaways

According to Bredt's rule, double bonds cannot exist at certain positions on organic molecules if the molecule's geometry deviates too far from what we learn in textbooks.

This rule has constrained chemists for a century.

A new paper in Science shows how to make molecules that violate Bredt’s rule, allowing chemists to find practical ways to make and use them in reactions.

UCLA chemists have found a big problem with a fundamental rule of organic chemistry that has been around for 100 years — it’s ...

Uncovered: the molecular basis of colorful parrot plumage

2024-10-31

A single enzyme fine-tunes red and yellow pigments in parrots’ polychromatic plumage, according to a new study. The findings reveal new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the evolution and display of color variation in one of nature’s most colorful birds. Colors play a central role in ecological adaptation and communication in the natural world. This is particularly true for birds, which are especially notable among animals for their wide range of vibrant plumage colors and patterns. Among birds, ...

Echolocating bats use acoustic mental maps to navigate long distances

2024-10-31

By blindfolding Kuhl's pipistrelle bats and tracking their movements with novel GPS technology, researchers show that the tiny creatures can navigate over several kilometers using only echolocation. The findings highlight the animal’s ability to create and use detailed mental acoustic maps of their surroundings. Echolocating bats are known for their ability to nimbly avoid obstacles and catch tiny prey using only sound. However, echolocation is short-ranged and highly directional, allowing for the detection of large objects within only a few dozen meters, limiting its effectiveness for navigation compared to other senses, like vision. ...

Sugar rationing in early life lowers risk for chronic disease in adulthood, post-World War II data shows

2024-10-31

Early-life sugar restriction – beginning in utero – can protect against diabetes and hypertension later in life, according to a new study leveraging data from post-World War II sugar rationing in the United Kingdom. The findings highlight critical long-term health benefits from reduced sugar intake during the first 1000 days of life. The first 1000 days from conception – from gestation until age 2 – is a critical period for long-term health. Poor diet during this window has been linked to negative health outcomes in adulthood. Despite dietary guidelines recommending zero added sugar in early life, high sugar exposure is ...

Indigenous population expansion and cultural burning reduced shrub cover that fuels megafires in Australia

2024-10-31

Indigenous burning practices in Australia once halved shrub cover, reducing available fuels and limiting wildfire intensity for thousands of years, but the removal of these practices following European colonization has led to an increase in the tinder that has fueled today’s catastrophic megafires, researchers report. The findings suggest that reintroducing cultural burning practices could provide a strategy to curb future fires. “Through detailed histories of Indigenous burning regimes across the world and Indigenous-led collaborations in contemporary wildfire management ...

Echolocating bats use an acoustic cognitive map for navigation

2024-10-31

Echolocating bats have been found to possess an acoustic cognitive map of their home range, enabling them to navigate over kilometer-scale distances using echolocation alone. This finding, recently published in Science, was demonstrated by researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, the Cluster of Excellence Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour at the University of Konstanz Germany, Tel Aviv University, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Would you be able to instantly recognize ...

Researchers solve medical mystery of neurological symptoms in kids

2024-10-31

Most people who visit a doctor when they feel unwell seek a diagnosis and a treatment plan. But for some 30 million Americans with rare diseases, their symptoms don’t match well-known disease patterns, sending families on diagnostic odysseys that can last years or even lifetimes.

But a cross-disciplinary team of researchers and physicians from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues from around the world has solved the mystery of a child with a rare genetic illness that did not fit any known disease. The team found a link between the child’s neurological symptoms and a genetic change that affects how proteins ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

[Press-News.org] How fruit flies achieve accurate visual behavior despite changing light conditionsResearchers identify neuronal networks and mechanisms that show how contrasts can be rapidly and reliably perceived even when light levels vary