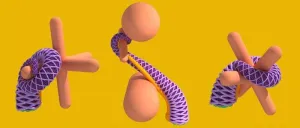

(Press-News.org) Mechanical engineering PhD candidate Arman Tekinalp, fellow graduate student Seung Hyun Kim, Professor Prashant Mehta, and Associate Professor Mattia Gazzola, all from the Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Their interdisciplinary collaboration also included Assistant Professor Noel Naughton (formerly a Beckman fellow) from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Virginia Tech alongside researchers from the Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology at Illinois and others from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and the University of South Florida. Their paper, “Topology, dynamics, and control of a muscle-architected soft arm,” which made the cover, describes an unprecedented computational model that captures the intricate muscular architecture of an octopus arm.

The model is in turn used to explain how structural mechanics dramatically simplify the control of the arm by automatically orchestrating complex three-dimensional recurrent motions out of simple muscle contraction patterns. The researchers have been collaborating on this work since 2019 with the overarching goal of developing “cyberoctopus” capability—in other words, creating robotic control systems that can replicate the complex movements of octopus arms.

In many animals including humans, a centralized brain serves as the decision-making hub, or controller, for the rest of the body. In contrast, octopus “brains” are distributed along the eight arms such that each arm can operate independently. Furthermore, the octopus’s physiology allows each arm to achieve a range of motion described by nearly infinite degrees of freedom, making computation extremely complex.

“The general motivation is to figure out how to control a complex system with many degrees of freedom and find an alternative to running expensive computations,” Gazzola said. “The octopus is an interesting animal model that has been studied since the 1980s. [Researchers] want to know the ‘secret’ to its abilities.”

“I find it very interesting to learn from live animals and translate some of the insights into ideas for soft robotic design,” Tekinalp said of his motivation for the study.

In previous efforts, the researchers worked with an interdisciplinary team to develop a theoretical approach to controlling a simplified octopus arm model. In this work, the team employed MRI and histological and biomechanical data to simulate a realistic arm comprised of nearly 200 intertwined muscle groups.

They also used image tracking to record the movements of a live octopus as it performed tasks in a tank. The octopus was placed on one side of a Plexiglas sheet with a hole through which only one arm could reach. In the experiments, a tempting object was placed on the opposite side of the sheet. The researchers could then video-capture the octopus reaching for and manipulating the object.

“It was almost like working with a little kid,” Gazzola recalled of observing the octopus. “You have to know how to approach [the octopus] and keep it engaged.”

From the imaging, the team extracted motion data and showed in simulation that their control approach could replicate the complex motions exhibited by the octopus arm. “We used topology and differential geometry to apply a set of fundamental theoretical results to the arm to describe its shape and control it via muscle actuation,” Gazzola said.

To describe the arm’s motion, the team developed simple muscle activation templates that could achieve complex 3D motion. “Instead of working with thousands of degrees of freedom, we related two topological quantities—writhe and twist—to muscle dynamics,” Gazzola said. “These two quantities are each controlled by different muscle groups whose coactivation gives rise to a third topological quantity, that describe the arm’s 3D morphological changes—that is, its motion.”

Their high-fidelity computational model is a milestone both in biology, where it can help explain the octopus’s impressive capability, and engineering. “The computational model is a useful testbed for roboticists to test their algorithms,” Mehta said.

The long-term study represents interdisciplinary efforts from multiple research groups and several students on campus over the years. Indeed, the team continues to change—Tekinalp, who will graduate in December 2024, will be going on to a postdoctoral position at the University of Maryland, College Park.

“For both Mattia and I, it was heartening to see the close cooperation between the students from our two research groups,” Mehta said.

Among the many next steps for this work, the researchers anticipate expanding their simulation techniques to investigate methods of controlling all eight arms in a collaborative fashion (e.g., mimicking how an octopus might work with multiple objects at once). They also hope to translate their findings into robotic prototypes for experimental testing.

“Our theoretical understanding is still an intuitive approach,” Gazzola said of additional next steps. “We want to develop an automated framework so that our octopus model can learn to perform tasks on its own.”

END

A new milestone in the study of octopus arms

2024-11-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fighting microplastics for a cleaner future

2024-11-11

Microplastics, plastics smaller than 5 millimeters, are littered across the world, contributing to global warming, disrupting food chains, and harming ecosystems with toxic chemicals. This is why Dr. Manish Shetty is working to break down plastics before they can get into the environment.

Creating sustainable chemicals and developing better waste management will contribute to better sustainability. This research is part of figuring out how to make green hydrogen available for waste management using catalysts.

Shetty’s research uses solvents in low amounts that also act as hydrogen sources to break down a specific class of plastics called ...

Tumor suppressor forms gel-like assemblies to sacrifice cancer cells

2024-11-11

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – November 11, 2024) There are processes in the human body that can suppress the growth and proliferation of cancer cells. These mechanisms, including those involving the tumor suppressor protein p53, are widely studied due to their critical role in disease. Through studies of proteins that regulate p53, scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital have uncoupled a previously unrecognized tumor suppression mechanism. Usually found at low levels in cells, the p14 Alternative Reading Frame protein (p14ARF) is expressed at higher levels under oncogenic stress and activates ...

New research uncovers how Barred Owls interact with urban areas and why it matters

2024-11-11

Baton Rouge, November 4, 2024 – Novel research just published in the American Ornithological Society journal, Ornithological Applications, has revealed noteworthy insights into how Barred Owls (Strix varia) interact with urban environments, with implications for both wildlife conservation and urban planning. This study, conducted by a team of biologists from Louisiana State University and other institutions, highlights the connection between owl habitat selection and an urban landscape, underscoring the ...

50 years of survey data confirm African elephant decline

2024-11-11

Habitat loss and poaching have driven dramatic declines in African elephants, but it is challenging to measure their numbers and monitor changes across the entire continent. A new study has analyzed 53 years of population survey data and found large-scale declines in most populations of both species of African elephants.

From 1964-2016, forest elephant populations decreased on average by 90%, and savanna elephant populations fell on average by 70%. In combination, populations declined by 77% on average. The study compiled survey data from 475 sites in 37 countries, making it the most comprehensive assessment of African elephants to date.

Declines ...

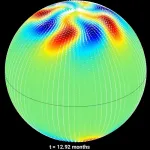

Swirling polar vortices likely exist on the Sun, new research finds

2024-11-11

EMBARGOED: Until 3 p.m. ET on Monday, Nov. 11, 2024

Contacts:

Laura Snider, NSF NCAR and UCAR Manager of Science Communications

lsnider@ucar.edu

303-827-1502

David Hosansky, NSF NCAR and UCAR Manager of Media Relations

hosansky@ucar.edu

720-470-2073

Like the Earth, the Sun likely has swirling polar vortices, according to new research led by the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR). But unlike on Earth, the formation and evolution of these vortices ...

Protein degradation strategy offers new hope in cancer therapy

2024-11-11

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- In drug discovery, targeted protein degradation is a method that selectively eliminates disease-causing proteins. A University of California, Riverside team of scientists has used a novel approach to identify protein degraders that target Pin1, a protein involved in pancreatic cancer development.

The team reports today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that it has designed agents that not only bind tightly to Pin1 but are designed to cause its destabilization and cellular ...

Mental fatigue leads to loss of self-control by putting brain areas to sleep

2024-11-11

Prolonged mental fatigue can wear down brain areas crucial for the individual ability to self-control, and cause people to behave more aggressively.

In a new multidisciplinary study published in the PNAS, a group of researchers from neuroscience and economics at the IMT School of Advanced Studies Lucca links the debated concept of "ego depletion", that is to say the diminution of willpower caused by previous exploitation of it, to physical changes in the areas that govern executive functions in the brain. In particular, the ...

Was ‘Snowball Earth’ a global event? New study delivers best proof yet

2024-11-11

Geologists have uncovered strong evidence from Colorado that massive glaciers covered Earth down to the equator hundreds of millions of years ago, transforming the planet into an icicle floating in space.

The study, led by the University of Colorado Boulder, is a coup for proponents of a long-standing theory known as Snowball Earth. It posits that from about 720 to 635 million years ago, and for reasons that are still unclear, a runaway chain of events radically altered the planet’s climate. Temperatures plummeted, and ice sheets that may have been several miles thick crept over every inch of Earth’s surface.

“This study presents the first physical evidence ...

Scientists issue call to action underlining importance of microbial solutions to tackle climate crisis

2024-11-11

Ahead of COP29, Applied Microbiology International (AMI) has partnered with leading global scientific organisations to issue a unified call to action, spotlighting microbial solutions as pivotal in combating climate change.

In a strategic publication, released in multiple high-impact scientific journals at once, the joint paper advocates for the establishment of a global science-driven climate task force. This initiative aims to expedite the deployment of microbiome technologies, providing stakeholders worldwide with access to effective and immediate solutions.

Signatories of the paper, ‘Microbial solutions must be deployed against the climate catastrophe’ ...

Ochsner Transplant Institute among site collaborators in New England Journal of Medicine HIV-to-HIV kidney transplant study

2024-11-11

NEW ORLEANS – The Ochsner Transplant Institute served as one of 26 U.S. transplant centers collaborating in an HIV-to-HIV kidney transplant study published by The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The article, Safety of Kidney Transplantation from Donors with HIV, details findings supporting HIV-to-HIV kidney transplants as safe and just as effective as those using organs from donors without HIV.

Human immunodeficiency virus, commonly known as HIV, attacks cells in the body that fight infection and there is currently no known cure. In the U.S.,1.2 million people are living with HIV. According to the National ...