(Press-News.org) NEW ORLEANS (November 14, 2024) — A new study from Uganda provides the first evidence to date that resistance to a lifesaving malaria drug may be emerging in the group of patients that accounts for most of the world’s malaria deaths: young African children suffering from serious infections. The study, presented today at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), documented partial resistance to the malaria drug artemisinin in 11 of 100 children, ages 6 months to 12 years, who were being treated for “complicated” malaria, that is, malaria with signs of severe disease caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

Also, 10 patients who were thought to have been cured suffered a repeat malaria attack within 28 days from the same strain of malaria that caused the original infection, suggesting that the initial treatment did not fully kill the infecting parasites.

“This is the first study from Africa showing that children with malaria and clear signs of severe disease are experiencing at least partial resistance to artemisinin,” said Chandy John, MD, MS, director of the Indiana University School of Medicine Ryan White Center for Infectious Diseases and Global Health, who is a co-author of the study along with colleagues Ruth Namazzi and Robert Opoka from Makerere University in Kampala in Uganda, Ryan Henrici from University of Pennsylvania, and Colin Sutherland from London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

John, who is a former ASTMH president said, “It’s also the first study showing a high rate of African children with severe malaria experiencing a subsequent malaria episode with the same strain within 28 days of standard treatment with artesunate, a derivative of artemisinin, and an artemisinin combination therapy (ACT).”

The arrival of artemisinin therapies some 20 years ago was a major advance in the global fight against malaria due to their power to rapidly cure infections — and because malaria parasites had developed resistance to other drugs. In 2008, there were reports from Cambodia noting partial resistance to artemisinin. By 2013 there was evidence that in some patients, the drug was completely failing. In the last few years, there has been increasing evidence that artemisinin resistance has now spread from that region into East Africa. The prospect of artemisinin losing its efficacy is particularly alarming for Africa and especially for African children. The region accounts for 95% of the 608,000 people who die from malaria each year and a large majority of malaria deaths in Africa are children under 5.

While all of the children in the study eventually recovered, 10 of them were infected with malaria parasites that harbor genetic mutations that have been linked to artemisinin-resistance in Southeast Asia. The study noted that while these mutations have been documented in Africa in less severe cases, this was the first time they have been seen in parasites that were causing complicated malaria in hospitalized African children. The term “complicated” malaria is used to define cases where the disease is at risk of causing potentially life-threatening complications, like severe anemia or brain-related problems known as cerebral malaria.

John said that researchers classified patients as suffering from partial resistance based on the World Health Organization’s defined half-life cutoff for parasite clearance of more than five hours, meaning requiring more than five hours to reduce a patient’s parasite burden by 50%. Two children required longer than the standard maximum of three days of artesunate therapy because they failed to clear their parasites with three days of therapy. He said longer treatment times increase the risk of poor outcomes. Also, he said that in Southeast Asia, the path to broadly resistant malaria parasites started with evidence of partial artemisinin resistance, and the concern is that pattern will be repeated in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Ugandan children in the study received what is considered to be the gold standard for treating complicated malaria infections: an intravenous infusion of artesunate followed by oral treatment with an ACT that combines another derivative of artemisinin, a drug called artemether, with the malaria drug lumefantrine.

John said the relatively high number of recurrent cases raises concerns that the efficacy of lumefantrine also may be declining. The drug is paired with artemether to make it harder for parasites to develop artemisinin resistance and also because lumefantrine stays in the body longer than artemether. Therefore, it can kill any remaining parasites not cleared by the shorter-acting artemisinin.

John said the study emerged from ongoing work in Uganda that is investigating outcomes of children who experience episodes of severe malaria. He said researchers pivoted to a focus on drug resistance because they noticed some children appeared to be slower to respond to the infusion of artesunate followed by an oral ACT.

“The fact that we started seeing evidence of drug resistance before we even started specifically looking for it is a troubling sign,” John said. “We were further surprised that, after we turned our focus to resistance, we also ended up finding patients who had recurrence after we thought they had been cured.”

###

About the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, founded in 1903, is the largest international scientific organization of experts dedicated to reducing the worldwide burden of tropical infectious diseases and improving global health. It accomplishes this through generating and sharing scientific evidence, informing health policies and practices, fostering career development, recognizing excellence, and advocating for investment in tropical medicine/global health research. For more information, visit astmh.org.

END

If you want to seem sincere and receive more responses to your texts, spell out words instead of abbreviating them, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association.

Researchers conducted eight experiments with a total of more than 5,300 participants using various methods. Across the experiments, individuals who used texting abbreviations were perceived as more insincere and were less likely to receive replies because they were seen as exerting less effort in text conversations. The research was published online in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

“In daily interactions, ...

Highlights:

The Atacama Desert is one of the most extreme habitats on Earth.

Atacama surface soil samples include a mix of DNA from inside and outside living cells.

A new technique allows researchers to separate external and internal DNA to identify microbes colonizing this hostile environment.

This approach for analyzing microbial communities could potentially be applied to other hostile environments, like those on other planets.

Washington, D.C.—The Atacama Desert, which runs along the Pacific Coast in Chile, is the driest place on the planet and, largely because of that aridity, hostile to most living things. ...

About The Study: This study found artemisinin partial resistance in Ugandan children with complicated malaria associated with the Pfkelch13 A675V variation and also found suboptimal 28-day efficacy of parenteral artesunate followed by oral artemether/lumefantrine therapy.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Chandy C. John, MD, MS, email chjohn@iu.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.22343)

Editor’s Note: Please see the ...

Sometimes the holes, or pores, in the molecular structure of a chemical only appear in the presence of certain conditions or other ‘guest’ molecules. This affects the field of separation—one of the most important processes in industry—but researchers have only just begun to unravel this phenomenon

Researchers have explored how a particular chemical can selectively trap certain molecules in the cavities of its structure—even though in normal conditions it has no such cavities. This innovative material with now-you-see-them-now-you-don’t holes could lead to more efficient methods for separating ...

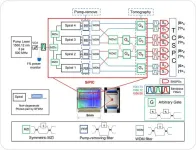

A group of South Korean researchers has successfully developed an integrated quantum circuit chip using photons (light particles). This achievement is expected to enhance the global competitiveness of the team in quantum computation research.

Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) announced that they have developed a system capable of controlling eight photons using a photonic integrated-circuit chip. With this system, they can explore various quantum phenomena, such as multipartite entanglement resulting from the interaction of the photons.

ETRI’s extensive research on silicon-photonic quantum ...

Collecting images of suspicious-looking skin growths and sending them off-site for specialists to analyze is as accurate in identifying skin cancers as having a dermatologist examine them in person, a new study shows.

According to the study authors, the findings add to evidence that such technology could help to reliably address diagnostic and treatment disparities for lower-income populations with limited access to dermatologists. It may also help dermatologists quickly catch cases of melanoma, a serious form of skin cancer that kills more than 8,000 Americans a year.

Their new system, which the researchers call SpotCheck, enables skin cancer specialists ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have identified new roles for a protein long known to protect against severe flu infection – among them, raising the minimum number of viral particles needed to cause sickness.

The protein also helps prevent unfamiliar viruses from mutating after they infect a new host, the study found – meaning its absence during an immune response could enable an animal virus spilled over to people to adapt rapidly to human hosts.

The combined findings by scientists at The Ohio State University add up to potential trouble for people deficient in the protein, called IFITM3 – especially if an avian or swine flu were to gain ...

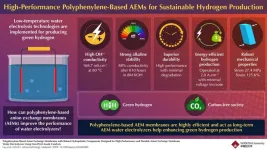

Hydrogen is a promising energy source due to its high energy density and zero carbon emissions, making it a key element in the shift toward carbon neutrality. Traditional hydrogen production methods, like coal gasification and steam methane reforming, release carbon dioxide, undermining environmental goals. Electrochemical water splitting, which yields only hydrogen and oxygen, presents a cleaner alternative. While proton exchange membrane (PEM) and alkaline water electrolyzers (AWEs) are available, they face limitations in either cost or efficiency. PEM electrolyzers, for instance, rely on costly platinum group metals (PGMs) as catalysts, whereas ...

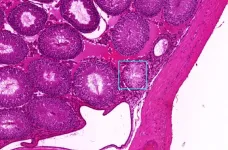

PULLMAN, Wash. – A “deep learning” artificial intelligence model developed at Washington State University can identify pathology, or signs of disease, in images of animal and human tissue much faster, and often more accurately, than people.

The development, detailed in Scientific Reports, could dramatically speed up the pace of disease-related research. It also holds potential for improved medical diagnosis, such as detecting cancer from a biopsy image in a matter of minutes, a process that typically takes ...

Concreting mistakes can be expensive. Concrete poured too quickly often leads to a lack of colour uniformity, irregularities in the structure and uneven surfaces. Particularly in the case of exposed concrete, expensive reworking using concrete cosmetics is then necessary, sometimes a wall may even have to be demolished. In addition, if the fresh concrete rises too quickly in the formwork, there is a certain risk potential for the workers, as this can cause the formwork to break. In their DigiCoPro project, Ralph Stöckl and ...