These cells — mainly blood and gut cells — are all replaced with new ones, but the way our bodies rid themselves of material could have profound implications for cancer therapies in a new approach developed by Stanford Medicine researchers.

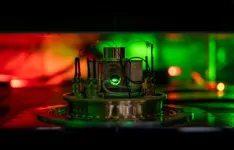

They aim to use this natural method of cell death to trick cancer cells into disposing of themselves. Their method accomplishes this by artificially bringing together two proteins in such a way that the new compound switches on a set of cell death genes, ultimately driving tumor cells to turn on themselves. The researchers describe their latest such compound in a paper published Oct. 4 in Science.

The idea came to Gerald Crabtree, MD, a professor of development biology, during a pandemic stroll through the forests of Kings Mountain, west of Palo Alto, California. As he walked, Crabtree, a longtime cancer biologist, was thinking about major milestones in biology.

One of the milestones he pondered was the 1970s-era discovery that cells trigger their own deaths for the greater good of the organism. Apoptosis turns out to be critical for many biological processes, including proper development of all organs and the fine-tuning of our immune systems. That system retains pathogen-recognizing cells but kills off self-recognizing ones, thus preventing autoimmune disease.

“It occurred to me, Well gee, this is the way we want to treat cancer,” said Crabtree, a co-senior author on the study who is the David Korn, MD, Professor in Pathology. “We essentially want to have the same kind of specificity that can eliminate 60 billion cells with no bystanders, so no cell is killed that is not the proper object of the killing mechanism.”

Traditional treatments for cancer — namely chemotherapy and radiation — often kill large numbers of healthy cells alongside the cancerous ones. To harness cells’ natural and highly specific self-destruction abilities, the team developed a kind of molecular glue that sticks together two proteins that normally would have nothing to do with one another.

Flipping the cancer script

One of these proteins, BCL6, when mutated, drives the blood cancer known as diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma. This kind of cancer-driving protein is also referred to as an oncogene. In lymphoma, the mutated BCL6 sits on DNA near apoptosis-promoting genes and keeps them switched off, helping the cancer cells retain their signature immortality.

The researchers developed a molecule that tethers BCL6 to a protein known as CDK9, which acts as an enzyme that catalyzes gene activation, in this case, switching on the set of apoptosis genes that BCL6 normally keeps off.

“The idea is, Can you turn a cancer dependency into a cancer-killing signal?” asked Nathanael Gray, PhD, co-senior author with Crabtree, the Krishnan-Shah Family Professor and a chemical and systems biology professor. “You take something that the cancer is addicted to for its survival and you flip the script and make that be the very thing that kills it.”

This approach — switching something on that is off in cancer cells — stands in contrast to many other kinds of targeted cancer therapies that inhibit specific drivers of cancer, switching off something that is normally on.

“Since oncogenes were discovered, people have been trying to shut them down in cancer,” said Roman Sarott, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford Medicine and co-first author on the study. “Instead, we’re trying to use them to turn signaling on that, we hope, will prove beneficial for treatment.”

When the team tested the molecule in diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma cells in the lab, they found that it indeed killed the cancer cells with high potency. They also tested the molecule in healthy mice and found no obvious toxic side effects, even though the molecule killed off a specific category of of the animals’ healthy B cells, a kind of immune cell, which also depend on BCL6. They’re now testing the compound in mice with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma to gauge its ability to kill cancer in a living animal.

Because the technique relies on the cells’ natural supply of BCL6 and CDK9 proteins, it seems to be very specific for the lymphoma cells — the BCL6 protein is found only in this kind of lymphoma cell and in one specific kind of B cell. The researchers tested the molecule in 859 different kinds of cancer cells in the lab; the chimeric compound killed only diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma cells.

And because BCL6 normally acts on 13 different apoptosis-promoting genes, the researchers hope their strategy will avoid the treatment resistance that seems so common in cancer. Cancer is often able to rapidly adapt to therapies that target only one of the disease’s weak spots, and some of these therapies may stop cancer from growing without killing the cells entirely. The research team hopes that by blasting the cells with multiple different cell death signals at once, the cancer will not be able to survive long enough to evolve resistance, although this idea remains to be tested.

“It’s sort of cell death by committee,” said Sai Gourisankar, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar and co-first author on the study. “And once a cancer cell is dead, that’s a terminal state.”

Crabtree and Gray, both members of the Stanford Cancer Institute, are co-founders of a biotech startup, Shenandoah Therapeutics, that aims to further test this molecule and a similar, previously developed molecule in hopes of gathering enough pre-clinical data to support launching clinical trials of the compounds. They also plan to build similar molecules that could target other cancer-driving proteins, including the oncogene Ras, which is a driver of several different kinds of cancer.

The study was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health (grants CA276167, CA163915, MH126720-01 and 5F31HD103339-03), the Mary Kay Foundation, the Schweitzer Family Fund, the SPARK Translational Research Program at Stanford University and Bio-X at Stanford University.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END