(Press-News.org) Coral adaptation to ocean warming and marine heatwaves will likely be overwhelmed without rapid reductions of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to an international team of scientists.

Their study, led by Dr. Liam Lachs of Newcastle University, reveals that coral heat tolerance adaptation via natural selection could keep pace with ocean warming, but only if Paris Agreement commitments are realised, limiting global warming to two degrees Celsius.

“The reality is that marine heatwaves are triggering mass coral bleaching mortality events across the world’s shallow tropical reef ecosystems, and the increasing frequency and intensity of these events is set to ramp up under climate change”, said Dr. Lachs.

“While emerging experimental research indicates scope for adaptation in the ability of corals to tolerate and survive heat stress, a fundamental question for corals has remained: can adaptation through natural selection keep pace with global warming? Our study shows that scope for adaptation will likely be overwhelmed for moderate to high levels of warming”

The international team of scientists studied the corals of Palau in the western Pacific Ocean, developing an eco-evolutionary simulation model of coral populations.

This model incorporates data on the thermal and evolutionary biology of common yet thermally sensitive corals, as well as their ecology. Published today in Science, the study simulates the consequences of alternative futures of global development and fossil fuel usage that were created by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Prof. Peter Mumby, a co-author of the study based at The University of Queensland, explains that “our world is expected to warm by 3-5 degrees by the end of this century if we do not achieve Paris Agreement commitments. Under such levels of warming, natural selection may be insufficient to ensure the survival of some of the more sensitive yet important coral species”.

“We can still have fairly healthy corals in the future, but this requires more aggressive reductions in global emissions and strategic approaches to coral reef management”

Dr. Lachs explains that “with current climate policies, we are on track for a middle-of-the road emissions scenario – leading to around 3 °C of warming – in which natural selection for heat tolerance could determine whether some coral populations survive.”

“From modelling this current emissions scenario, we expect to see profound reductions in reef health and an elevated risk of local extinction for thermally sensitive coral species. We also acknowledge that considerable uncertainty remains in the “evolvability” of coral populations”.

Study co-author Dr. James Guest, who leads the Coralassist Lab, says there is an urgent need to understand how to design climate-smart management options for coral reefs.

“We need management actions that can maximise the natural capacity for genetic adaptation, whilst also exploring whether it will be possible to increase the likelihood of adaptation in wild populations."

“One such option, still at the experimental stages to date, would be the use of targeted assisted evolution interventions that, for instance, could improve heat tolerance through selective breeding,” Dr. Guest said, referring to a separate paper recently published by the Coralassist Lab.

Coral reefs are remarkably diverse and critically important marine ecosystems. “Taken together”, says Dr. Lachs, “the results of our models suggest that genetic adaptation could offset some of the projected loss of coral reef functioning and biodiversity over the 21st Century, if rapid climate action can be achieved”.

END

Coral adaptation unlikely to keep pace with global warming

2024-11-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bioinspired droplet-based systems herald a new era in biocompatible devices

2024-11-28

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 19:00 GMT / 14:00 ET THURSDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2024

Bioinspired droplet-based systems herald a new era in biocompatible devices

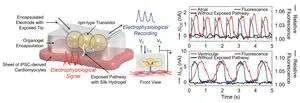

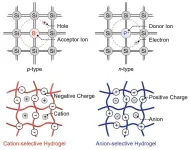

Oxford University researchers have developed a set of biocompatible devices, which can replicate or surpass many electronic functions but use ions as the signal carriers.

The ‘dropletronic devices’ are made from miniature soft hydrogel droplets and can be combined to produce diodes, transistors, reconfigurable logic gates, and memory storage devices that mimic biological synapses.

The research team generated a biocompatible, dropletronic ...

A fossil first: Scientists find 1.5-million-year-old footprints of two different species of human ancestors at same spot

2024-11-28

More than a million years ago, on a hot savannah teeming with wildlife near the shore of what would someday become Lake Turkana in Kenya, two completely different species of hominins may have passed each other as they scavenged for food.

Scientists know this because they have examined 1.5-million-year-old fossils they unearthed and have concluded they represent the first example of two sets of hominin footprints made about the same time on an ancient lake shore. The discovery will provide more insight into human evolution and how species cooperated and competed with ...

The key to “climate smart” agriculture might be through its value chain

2024-11-28

In 2023, the United Nations climate conference (COP28) officially recognized the importance of agriculture in influencing and mitigating climate change. In a Policy Forum, Johan Swinnen and colleagues offer an approach to overcome challenges related to improving climate-sensitive farming practices across the globe. They discuss the importance of working with Agricultural Value Chains (AVC) by incentivizing small businesses who play an important role in the support of small- and medium-sized farms. This would involve both upstream enterprises related to seeds, fertilizer, ...

These hibernating squirrels could use a drink—but don’t feel the thirst

2024-11-28

The thirteen-lined ground squirrel doesn’t drink during its winter hibernation, even though systems throughout its body are crying out for water. Madeleine Junkins and colleagues now show that the squirrel suppresses the need to quench its thirst by reducing the activity of a set of neurons in highly vascularized brain structures called circumventricular organs, which act as a specialized connection point between brain, blood circulation and cerebrospinal fluid. The study by Junkins et al. helps explain how some hibernating animals ignore the powerful physiological drive to seek out water ...

New footprints offer evidence of co-existing hominid species 1.5 million years ago

2024-11-28

Newly discovered footprints show that at least two hominid species were walking through the muddy submerged edge of a lake in Kenya’s Turkana Basin at the same time, about 1.5 million years ago. The find from the famous hominid fossil site of Koobi Fora described by Kevin Hatala and colleagues provides physical evidence for the co-existence of multiple hominid lineages in the region—something that has only been inferred previously from overlapping dates for scattered fossils. Based on information on gait and stance gleaned from the footprints, Hatala et al. think that the two species were Homo erectus and Paranthropus ...

Moral outrage helps misinformation spread through social media

2024-11-28

Social media posts containing misinformation evoke more moral outrage than posts with trustworthy information, and that outrage facilitates the spread of misinformation, according to a new study by Killian McLoughlin and colleagues. The researchers also found that people are more likely to share outrage-evoking misinformation without reading it first. The findings suggest that attempts to mitigate the online spread of misinformation by encouraging people to check its accuracy before sharing may not be successful, the researchers ...

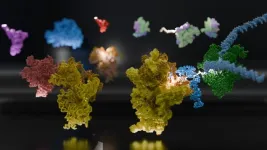

U-M, multinational team of scientists reveal structural link for initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria

2024-11-28

IMAGE

ANN ARBOR—Within a cell, DNA carries the genetic code for building proteins.

To build proteins, the cell makes a copy of DNA, called mRNA. Then, another molecule called a ribosome reads the mRNA, translating it into protein. But this step has been a visual mystery: scientists previously did not know how the ribosome attaches to and reads mRNA.

Now, a team of international scientists, including University of Michigan researchers, have used advanced microscopy to image how ribosomes recruit to mRNA while it's being transcribed by an enzyme called RNA polymerase, or RNAP. Their results, which examine the process in bacteria, are published in the journal ...

New paper calls for harnessing agrifood value chains to help farmers be climate-smart

2024-11-28

Washington DC, November 28, 2024: The global food system is uniquely vulnerable to climate impacts, making adaptation of paramount importance. While contributing roughly one-third of total anthropogenic emissions, food systems around the world fortunately also hold immense potential for mitigation through improved practices and land use. A new article published today in Science emphasizes the critical role of agrifood value chains (AVCs) in supporting both adaptation and mitigation at the farm level.

Authored by Johan Swinnen (International Food Policy Research Institute), Loraine Ronchi (World Bank Group), and Thomas Reardon (Michigan State University and IFPRI), the paper pushes back ...

Preschool education: A key to supporting allophone children

2024-11-28

Learning French while also developing language skills in one’s mother tongue is no easy task. As a result, allophone children often face learning and communication difficulties in kindergarten, which can negatively impact their educational journey. However, solutions are emerging.

According to a study led by Sylvana Côté, preschool education services significantly help bridge the gap between children whose mother tongue is French and those for whom French is a second or even a third language.

Professor Côté, from the School of Public Health at the Université de Montréal (ESPUM), is the director of the Observatory ...

CNIC scientists discover a key mechanism in fat cells that protects the body against energetic excess

2024-11-28

A team at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), led by Professor Miguel Ángel del Pozo Barriuso, who heads the Mechanoadaptation and Caveolae Biology group at the CNIC, has identified an essential mechanism in fat cells (adipocytes) that enables them to enlarge safely to store energy. This process avoids tissue damage and protects the body from the toxic effects of accumulating fat molecules (lipids) in inappropriate places. The results, published in Nature Communications, signify a major advance in the understanding of metabolic diseases. Moreover, this discovery ...