(Press-News.org) Construction materials such as concrete and plastic have the potential to lock away billions of tons of carbon dioxide, according to a new study by civil engineers and earth systems scientists at the University of California, Davis and Stanford University. The study, published Jan. 10 in Science, shows that combined with steps to decarbonize the economy, storing CO2 in buildings could help the world achieve goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“The potential is pretty large,” said Elisabeth Van Roijen, who led the study as a graduate student at UC Davis.

The goal of carbon sequestration is to take carbon dioxide, either from where it is being produced or from the atmosphere, convert it into a stable form and store it away from the atmosphere where it cannot contribute to climate change. Proposed schemes have involved, for example, injecting carbon underground or storing it in the deep ocean. These approaches pose both practical challenges and environmental risks.

“What if, instead, we can leverage materials that we already produce in large quantities to store carbon?” Van Roijen said.

Working with Sabbie Miller, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis, and Steve Davis at Stanford University, Van Roijen calculated the potential to store carbon in a wide range of common building materials including concrete (cement and aggregates), asphalt, plastics, wood and brick.

More than 30 billion tons of conventional versions of these materials are produced worldwide every year.

Concrete potential

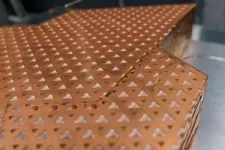

The carbon-storing approaches studied included adding biochar (made by heating waste biomass) into concrete; using artificial rocks that can be loaded with carbon as concrete and asphalt pavement aggregate; plastics and asphalt binders based on biomass rather than fossil petroleum sources; and including biomass fiber into bricks. These technologies are at different stages of readiness, with some still being investigated at a lab or pilot scale and others already available for adoption.

Researchers found that while bio-based plastics could take up the largest amount of carbon by weight, by far the largest potential for carbon storage is in using carbonated aggregates to make concrete. That’s because concrete is by far the world’s most popular building material: Over 20 billion tons are produced every year.

“If feasible, a little bit of storage in concrete could go a long way,” Miller said. The team calculated that if 10% of the world’s concrete aggregate production were carbonateable, it could absorb a gigaton of CO2.

The feedstocks for these new processes for making building materials are mostly low-value waste materials such as biomass, Van Roijen said. Implementing these new processes would enhance their value, creating economic development and promoting a circular economy, she said.

Some technology development is needed, particularly in cases where material performance and net-storage potential of individual manufacturing methods must be validated. However, many of these technologies are just waiting to be adopted, Miller said.

Van Roijen is now a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory. The work was supported by Miller’s CAREER grant from the National Science Foundation.

END

Storing carbon in buildings could help address climate change

2025-01-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

May the force not be with you: Cell migration doesn't only rely on generating force

2025-01-09

By Beth Miller

In mechanobiology, cells’ forces have been considered fundamental to their enhanced function, including fast migration. But a group of researchers in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis has found that cells can generate and use lower force yet move faster than cells generating and using high forces, turning the age-old assumption of force on its head.

The laboratory of Amit Pathak, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science, found that groups of cells moved faster with lower force when adhered to soft surfaces with aligned collagen fibers. Cells have been thought to continually generate ...

NTU Singapore-led discovery poised to help detect dark matter and pave the way to unravel the universe’s secrets

2025-01-09

Researchers led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have developed a breakthrough technique that could lay the foundations for detecting the universe’s “dark matter” and bring scientists closer than before to uncovering the secrets of the cosmos.

The things we can see on Earth and in space – visible matter like rocks and stars – make up only a small portion of the universe, as scientists believe that 85 per cent of matter in the cosmos comprises invisible dark matter. This mysterious substance ...

Researchers use lab data to rewrite equation for deformation, flow of watery glacier ice

2025-01-09

AMES, Iowa – Neal Iverson started with two lessons in ice physics when asked to describe a research paper about glacier ice flow that has just been published by the journal Science.

First, said the distinguished professor emeritus of Iowa State University’s Department of the Earth, Atmosphere, and Climate, there are different types of ice within glaciers. Parts of glaciers are at their pressure-melting temperature and are soft and watery.

That temperate ice is like an ice cube left on a kitchen counter, with meltwater ...

Did prehistoric kangaroos run out of food?

2025-01-09

Prehistoric kangaroos in southern Australia had a more general diet than previously assumed, giving rise to new ideas about their survival and resilience to climate change, and the final extinction of the megafauna, a new study has found.

The new research, a collaboration between palaeontologists from Flinders University and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT), used advanced dental analysis techniques to study microscopic wear patterns on fossilised kangaroo teeth.

The findings, published in Science, suggest that many species of kangaroos were generalists, able to adapt to diverse diets in response to environmental changes.

More ...

HKU Engineering Professor Kaibin Huang named Fellow of the US National Academy of Inventors

2025-01-09

The US National Academy of Inventors (NAI) announced the 2024 Class of Fellows on December 10, 2024. Professor Kaibin Huang of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EEE), Faculty of Engineering, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), was elected a 2024 Fellow in recognition of his inventions and contributions in tackling real-world issues.

Election to NAI Fellow status is the highest professional distinction accorded to academic inventors who have demonstrated a prolific spirit of innovation in creating or facilitating outstanding inventions that have made a tangible impact on ...

HKU Faculty of Arts Professor Charles Schencking elected as Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities

2025-01-09

Professor Charles Schencking, Professor of History of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), has been elected as a Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities (the Academy).

The Australian Academy of the Humanities was established in 1969 by Royal Charter to advance knowledge of, and the pursuit of excellence in, the Humanities. It is an independent, not-for-profit organisation with a Fellowship of over 730 distinguished humanities researchers, leaders, and practitioners ...

Rise in post-birth blood pressure in Asian, Black, and Hispanic women linked to microaggressions

2025-01-09

A study of more than 400 Asian, Black and Hispanic women who had recently given birth found that racism through microaggressions may be linked to higher blood pressure during the period after their baby was born, according to a new study by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. More than one-third of the mothers reported experiencing at least one microaggression related to being a woman of color during or after their pregnancy. The research conducted with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania ...

Weight changes and heart failure risk after breast cancer development

2025-01-09

About The Study: In this nationwide cohort study in the Republic of Korea, postdiagnosis weight gain was associated with an increased risk of heart failure after breast cancer development, with risk escalating alongside greater weight gain. The findings underscore the importance of effective weight intervention in the oncological care of patients with breast cancer, particularly within the first few years after diagnosis, to protect cardiovascular health.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Dong Wook Shin, MD, DrPH, MBA, email dwshin@skku.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

Changes in patient care experience after private equity acquisition of US hospitals

2025-01-09

About The Study: This study found that patient care experience worsened after private equity acquisition of hospitals. These findings raise concern about the implications of private equity acquisitions on patient care experience at U.S. hospitals.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Rishi K. Wadhera, MD, MPP, MPhil, email rwadhera@bidmc.harvard.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.23450)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, ...

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women in the US

2025-01-09

About The Study: The results of this study suggest that addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black women requires a multifaceted approach that acknowledges historical traumas, provides clear and transparent safety information, and avoids coercive vaccine promotion strategies. These findings emphasize the need for health care practitioners and public health officials to prioritize trust-building, engage community leaders, and tailor interventions to address the unique concerns of Black women to improve vaccine confidence and uptake.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Brittany C. Slatton, PhD, email brittany.slatton@tsu.edu.

To access the ...