(Press-News.org) PULLMAN, Wash. — College students who spent a little bit of free time each week interacting with therapy dogs on campus during their first semester experienced fewer signs of stress and depression than those who did not.

That’s according to the PAWs4US study, a new paper published in Pets that examined how regular, long-term access to an animal-assisted drop-in program at Washington State University influenced first-year students’ mental health.

The study found that students who engaged with therapy dogs in repeated, unstructured sessions over several months not only reported lower stress and depression levels, but also showed increased self-compassion. The findings suggest that simply having the opportunity to regularly spend time with therapy dogs in an informal setting provides sustained mental health benefits.

“We know that structured programs help, but we wanted to see if giving students complete autonomy in how they interact with the dogs could be just as beneficial,” said Patricia Pendry, corresponding author of the study and a WSU professor of human development. “This mirrors real-life pet ownership more closely and may make it easier for universities to implement similar programs.”

For the study, Pendry and doctoral candidate Alexa Carr set out to build on Pendry’s earlier research showing that even brief physical interactions with therapy dogs can lower cortisol levels. Pendry’s prior work has also shown that highly structured programs that incorporated therapy animals into workshops focused on stress management techniques showed positive effects on students’ well-being and learning.

This latest work expands the scope by analyzing the effects of sustained access to unstructured programs with therapy animals and providing regular access over an entire semester. Additionally, instead of prescribed sessions, students were free to drop in, interact with therapy dogs as they pleased, and stay as long as they wanted for up to two hours.

The researchers recruited 145 first-year students who left a family pet behind at home to attend college for their analysis. Participants were randomly assigned to either a seven-session drop-in therapy dog program or a waitlisted control group. Those in the program could pet, sit with, or talk to the dogs in a relaxed, informal environment in a large conference room on the WSU Pullman campus comfortably arranged to include secluded seating areas. The canine companions featured in the study were provided by Palouse Paws, a local representative of a national organization called Pet Partners that specializes in providing teams to conduct animal assisted interventions.

By tracking participants’ wellbeing throughout the semester, researchers found that students in the therapy dog group had significantly lower rates of depression, stress and worry compared to those in the control group. They also reported increased self-compassion, which has been linked to better emotional regulation and overall well-being. Students experienced less decline in wellbeing and mental health symptoms, a phenomenon that is prevalent for incoming freshman.

While therapy dogs played a central role, the researchers believe that the surrounding environment also contributed to students’ well-being. “It’s likely a combination of sitting quietly, petting the dog, talking to other students and engaging with the handlers that contributes to student well-being,” Pendry said.

Pendry’s team also tracked students’ participation patterns and found that those who attended multiple sessions saw the most benefit. “Regular, sustained interactions with therapy dogs seem to have a cumulative effect,” said Carr, who recently completed her dissertation featuring this research. “This suggests that universities may want to consider offering ongoing unstructured programs rather than one-time events.”

Implications for student mental health support

With college student mental health concerns on the rise, universities are increasingly turning to animal-assisted programs, according to Pendry, a former president of the International Society for Anthrozoology. She hopes WSU’s research will encourage more schools to offer similar drop-in therapy dog programs but stresses the need for careful, evidence-based application.

“This is a relatively easy, low-cost way to support student well-being,” Pendry said. “You don’t need a structured curriculum—just an inviting space where students can interact with the dogs and their handlers on their own terms in a way that ensures animal welfare and participant safety.”

Moving forward, Pendry and her collaborators plan to expand the scope of their research to examine whether students who did not leave childhood pets at home experience similar benefits.

END

Regular access to therapy dogs boosts first-year students’ mental health

2025-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The complicated question of how we determine who has an accent

2025-02-13

COLUMBUS, Ohio – How do you tell if someone has a particular accent? It might seem obvious: You hear someone pronounce words in a way that is different from “normal” and connect it to other people from a specific place.

But a new study suggests that might not be the case.

“People probably don’t learn who has an accent from hearing someone talk and thinking, ‘huh, they sound funny’ – even though sometimes it feels like that’s how we do it,” said Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, author of the study and associate professor of linguistics at The Ohio State University.

Accents may be ...

NITech researchers shed light on the mechanisms of bacterial flagellar motors

2025-02-13

When speaking of motors, most people think of those powering vehicles and human machinery. However, biological motors have existed for millions of years in microorganisms. Among these, many bacterial species have tail-like structures—called flagella—that spin around to propel themselves in fluids. These movements employ protein complexes known as the “flagellar motor.”

This flagellar motor consists of two main components: the rotor and the stators. The rotor is a large rotating structure, anchored to the cell membrane, that turns the flagellum. On the other hand, the stators are smaller ...

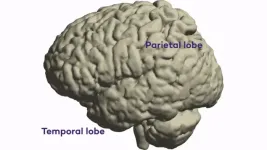

Study maps new brain regions behind intended speech

2025-02-13

Broca’s aphasia is caused by damage to the frontal lobe, leaves patients unable to say what they intend to say

First study to identify regions outside the frontal lobe that encode the intent to speak

Critical for technology to avoid decoding a patient’s thoughts that are not intended to be spoken aloud

CHICAGO --- Imagine seeing a furry, four-legged animal that meows. Mentally, you know what it is, but the word “cat” is stuck on the tip of your tongue.

This phenomenon, known as Broca’s aphasia or expressive aphasia, is a language disorder that affects a person’s ability to speak or ...

Next-gen Alzheimer’s drugs extend independent living by months

2025-02-13

In the past two years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two novel Alzheimer’s therapies, based on data from clinical trials showing that both drugs slowed the progression of the disease. But while the approvals of lecanemab and donanemab, both antibody therapies that clear plaque-causing amyloid proteins from the brain, were greeted with enthusiasm by some Alzheimer’s researchers, the response of patients has been muted. According to physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s, many patients found it difficult to understand what the clinical trials results — presented as “percent decrease in ...

Jumping workouts could help astronauts on the moon and Mars, study in mice suggests

2025-02-13

Jumping workouts could help astronauts prevent the type of cartilage damage they are likely to endure during lengthy missions to Mars and the Moon, a new Johns Hopkins University study suggests.

The research adds to ongoing efforts by space agencies to protect astronauts against deconditioning/getting out of shape due to low gravity, a crucial aspect of their ability to perform spacewalks, handle equipment and repairs, and carry out other physically demanding tasks.

The study, which shows knee cartilage in mice grew healthier following jumping exercises, appears ...

Guardian molecule keeps cells on track – new perspectives for the treatment of liver cancer

2025-02-13

A guardian molecule ensures that liver cells do not lose their identity. This has been discovered by researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), the Hector Institute für Translational Brain Research (HITBR), and from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). The discovery is of great interest for cancer medicine because a change of identity of cells has come into focus as a fundamental principle of carcinogenesis for several years. The Heidelberg researchers were able to show ...

Solar-powered device captures carbon dioxide from air to make sustainable fuel

2025-02-13

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts it into sustainable fuel, using sunlight as the power source.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, say their solar-powered reactor could be used to make fuel to power cars and planes, or the many chemicals and pharmaceuticals products we rely on. It could also be used to generate fuel in remote or off-grid locations.

Unlike most carbon capture technologies, the reactor developed by the Cambridge researchers does not require fossil-fuel-based power, or the transport and storage of carbon dioxide, but instead converts atmospheric CO2 into something useful using sunlight. ...

Bacteria evolved to help neighboring cells after death, new research reveals

2025-02-13

Darwin’s theory of natural selection provides an explanation for why organisms develop traits that help them survive and reproduce.

Because of this, death is often seen as a failure rather than a process shaped by evolution.

When organisms die, their molecules need to be broken down for reuse by other living things.

Such recycling of nutrients is necessary for new life to grow.

Now a study led by Professor Martin Cann of ...

Lack of discussion drives traditional gender roles in parenthood

2025-02-13

Conversations about parental duties continue to be led by mothers, even if both parents earn the same amount of money, finds a new study by a UCL researcher.

A new study by Dr Clare Stovell (IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education & Society), published in the Journal of Family Studies, highlights how a lack of discussion between parents about important choices such as parental leave, work and childcare is perpetuating traditional gender roles.

The study found that women usually lead the conversations and there is little discussion about the man’s work schedule, even in cases where the woman earns as much or more than her partner.

Dr Stovell said: “These interviews ...

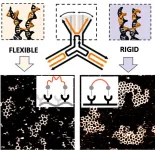

Scientists discover mechanism driving molecular network formation

2025-02-13

Covalent bonding is a widely understood phenomenon that joins the atoms of a molecule by a shared electron pair. But in nature, patterns of molecules can also be connected through weaker, more dynamic forces that give rise to supramolecular networks. These can self-assemble from an initial molecular cluster, or crystal, and grow into large, stable architectures.

Supramolecular networks are essential for maintaining the structure and function of biological systems. For example, to ‘eat’, cells rely ...