(Press-News.org) The evolutionary roots of human dominance and aggression remain central to social and political behaviour, and without conscious intervention these primal survival drives will continue to fuel inequality and division.

These are the arguments of a medical professor who, as global conflicts rise and democracies face growing challenges, says understanding how dominance and tribal instincts fuel division is more critical than ever.

In A New Approach to Human Social Evolution, Professor Jorge A. Colombo MD, PhD explores neuroscience, anthropology, and behavioural science to provide a new perspective on human social evolution.

He argues that fundamental behavioural drives – such as dominance, survival instincts, and competition – are hardwired into our species and continue to shape global politics, economic inequality, and social structures today. Without a conscious effort to counteract these instincts, we risk perpetuating the cycles of power struggles, inequality, and environmental destruction that define much of human history.

“In an era marked by rising authoritarianism, economic inequality, environmental crises, and nationalism, understanding how ancient survival mechanisms continue to shape human behaviour is crucial,” he explains. “With increasing polarisation in politics, conflicts over resources, and the struggle for social justice, I contend that only through education and universal values can humanity transcend these instincts to foster a more sustainable and equitable society.”

Professor Colombo, who is a former Full Professor at the University of South Florida (USA) and Principal Investigator at the National Research Council (CONICET, Argentina), explains how current human behaviour evolved based on an ancient heritage of animal drives which has been progressively built and placed into practice— grounded on survival, social gain, and profit— and is compressed to our basic neural systems and basic survival behavioural construction.

When humans shifted from prey to universal predator, it affected the organization of the human brain, he argues. However, the human species also had to contend with the notion of mortality, and so in our core neural circuits (mainly in the basal brain) survive our basal drives (reproductive, territorial, survival, feeding), basic responses (fight, flight), and the thresholds for their behavioural expression.

Over time, he explains, thanks to the brain’s plasticity, it has added a neurobiological scaffolding on top of our animal drives, allowing for the emergence of traits such as creativeness, cognitive expansion, artistic expression, progressive toolmaking, and rich verbal communication.

Nevertheless, he argues, these traits did not deactivate or suppress those ancient drives and only succeeded in diverting (camouflaging) their expression or repressing them temporarily.

He argues that humans are bound to their ancestral demands imprinted as a set of basic drives (territorialism, reproduction, survival, secure feeding sources, dominance, and cumulative behaviour), which exist in friction with our cultural drives.

“Ancient animal survival drives persist in humans, masked under various behavioural paradigms. Fight and flight remain basic behavioural principles. Even subdued under religious or mystic beliefs, aggressive and defensive behaviours emerge to defend or fight for even the most sophisticated peaceful beliefs, and events throughout humankind’s history support this evidence,” he explains.

He points to examples of dominance in politics (military oppression, propaganda, or financial repression), religion (punishing gods, esoteric menaces), and education (forms of punishment and thought process conditioning).

However, dominance exerted through political, economic, social class, or military power adds privileged structures to social construction, Colombo argues.

As a dominant species with evolved cultural and technological strategies, it has resulted in the over-exploitation of natural resources, the development of arms of massive destruction, strategies to foster massive consumerism, and political means to manipulate public opinion, which also, in turn, create poverty, deprivation, marginalization, and oppression.

He argues that without education and the promotion of universal values involving individual opportunities to evolve and protect the environment, more communities will become undernourished, impoverished, and without access to primary healthcare or adequate education for the continuous changes in the modern world.

He points to AI as an example of a growing, uneven educational gap that would reinforce socioeconomic disparity and social inequality. He argues that people should proactively create policies to work towards a viable, multicultural, equitable humanity and an ecologically sustainable planet.

“The aggressiveness, cruelties, social inequities, and unrelenting individual and socioeconomic class ambitions are the best evidence that humans must first recognize and assume their fundamental nature to change their ancestral drive,” he suggests. “Profound cultural changes are only possible and enduring if humans come to grips with their actual primary condition.”

END

Are we still primitive? How ancient survival instincts shape modern power struggles

2025-02-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Near-complete skull discovery reveals ‘top apex’, leopard-sized “fearsome” carnivore

2025-02-17

A rare discovery of a nearly complete skull in the Egyptian desert has led scientists to the “dream” revelation of a new 30-million-year-old species of the ancient apex predatory carnivore, Hyaenodonta.

Bearing sharp teeth and powerful jaw muscles, suggesting a strong bite, the newly-identified ‘Bastetodon’ was a leopard-sized “fearsome” mammal. It would have been at the top of all carnivores and the food chain when our own monkey-like ancestors were evolving.

Findings, published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, detail ...

Reintroducing wolves to Scottish Highlands could help address climate emergency

2025-02-17

University of Leeds news

Embargoed until 05:01 GMT, 17 February

Reintroducing wolves to the Scottish Highlands could lead to an expansion of native woodland which could take in and store one million tonnes of CO2 annually, according to a new study led by researchers at the University of Leeds.

The team modelled the potential impact that wolves could have in four areas classified as Scottish Wild Land, where the eating of tree saplings by growing red deer populations is suppressing natural regeneration of trees and woodland.

They used a predator–prey model to ...

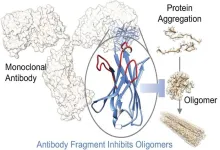

New antibody discovery platform can inform Alzheimer's and Parkinson's

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – In diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, specific proteins misfold and clump together, forming toxic aggregates that damage brain cells. The process of proteins spontaneously clumping is called protein aggregation and researchers have developed novel methods to generate aggregate-specific antibodies as specific probes or modulators of the aggregation process.

This new method overcomes significant challenges in characterizing these complex and often transient protein structures. The work will be presented at the 69th Biophysical ...

The Biophysical Journal names Marcel P. Goldchen-Ohm the 2024 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – Marcel P. Goldschen-Ohm, of the University of Texas at Austin, USA will be honored as the recipient of the Biophysical Journal Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator Award at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society, held February 15-19 in Los Angeles, California. This award recognizes the work of outstanding early career investigators in biophysics. The winning paper is titled “GABAA Receptor Subunit M2-M3 Linkers Have Asymmetric Roles in Pore Gating and Diazepam Modulation.” The paper was published in Volume 123, Issue 14 of Biophysical Journal.

GABAA receptors mediate inhibitory synaptic signaling ...

A new system to study phytoplankton: Crucial species for planet Earth

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – Phytoplankton, tiny plant-like organisms in the ocean, are incredibly important for life on Earth. They're a major food source for many sea creatures and produce almost half the oxygen we breathe. They also help control the climate by soaking up a lot of carbon dioxide, a gas that contributes to global warming.

Scientists want to learn more about how these phytoplankton use sunlight to make energy and oxygen, which can be useful in the context of environmental monitoring during ...

Scientists discover "genetic weak spot" in endangered Italian bear population

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – The Apennine brown bear, also known as the Marsican brown bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus), is a unique and critically endangered subspecies of brown bear found only in the remote and rugged Apennine Mountains of central Italy.

A new study by the Italian Endemixit project (endemixit.com) reveals a potentially critical genetic flaw in the endangered Apennine brown bear population of Italy, offering insights that could help boost conservation efforts. The work will be presented at the 69th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting, to be held February 15 - 19, 2025 in Los Angeles.

This distinct population has been isolated for centuries, evolving unique physical ...

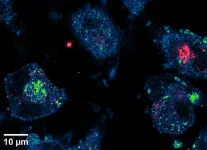

New insights into Alzheimer's brain inflammation

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – Brain inflammation, while a crucial part of the body's immune response, takes on a detrimental role in Alzheimer's disease. Unlike the acute, short-lived inflammation that combats infection, the inflammation associated with Alzheimer's becomes chronic and persistent. Scientists have been trying to understand why this happens.

New research reveals key differences in how the brain's immune system responds to the disease compared to a bacterial infection. The work will be presented at the 69th ...

Sweet taste receptors in the heart: A new pathway for cardiac regulation

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – In a surprising discovery, scientists have found that the heart possesses "sweet taste" receptors, similar to those on our tongues, and that stimulating these receptors with sweet substances can modulate the heartbeat. This research opens new avenues for understanding heart function and potentially for developing novel treatments for heart failure.

While taste receptors are traditionally associated with the tongue and our ability to perceive flavors, recent studies ...

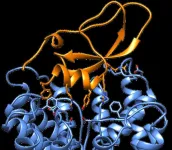

Designing antivirals for shape-shifting viruses

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – Viruses, like those that cause COVID-19 or HIV, are formidable opponents once they invade our bodies. Antiviral treatments strive to block a virus or halt its replication. However, viruses are dynamic—constantly evolving and changing shape, which can make designing antiviral treatments a challenge.

But new research utilizes an innovative computational modeling approach to capture the complex and diverse shapes that viral proteins can adopt. The work will be presented at the 69th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting, to be held February 15 - 19, 2025 in Los Angeles.

This new approach, implemented in the open-source Integrative Modeling Platform ...

Cone snail toxin inspires new method for studying molecular interactions

2025-02-15

ROCKVILLE, MD – When scientists develop new molecules—whether for the purposes of agriculture, species control, or life-savings drugs—it’s important to know exactly what its targets are. Thoroughly understanding a molecule's interactions, both intended and unintended, is crucial for ensuring its safety and efficacy.

A cone snail toxin known to affect both insects and fish inspired Weizmann Institute scientists to develop a new way of finding molecular targets. By combining artificial intelligence with traditional ...