(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- RNA splicing is a cellular process that is critical for gene expression. After genes are copied from DNA into messenger RNA, portions of the RNA that don’t code for proteins, called introns, are cut out and the coding portions are spliced back together.

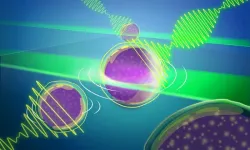

This process is controlled by a large protein-RNA complex called the spliceosome. MIT biologists have now discovered a new layer of regulation that helps to determine which sites on the messenger RNA molecule the spliceosome will target.

The research team discovered that this type of regulation, which appears to influence the expression of about half of all human genes, is found throughout the animal kingdom, as well as in plants. The findings suggest that the control of RNA splicing, a process that is fundamental to gene expression, is more complex than previously known.

“Splicing in more complex organisms, like humans, is more complicated than it is in some model organisms like yeast, even though it's a very conserved molecular process. There are bells and whistles on the human spliceosome that allow it to process specific introns more efficiently. One of the advantages of a system like this may be that it allows more complex types of gene regulation,” says Connor Kenny, an MIT graduate student and the lead author of the study.

Christopher Burge, the Uncas and Helen Whitaker Professor of Biology at MIT, is the senior author of the study, which appears today in Nature Communications.

Building proteins

RNA splicing, a process discovered in the late 1970s, allows cells to precisely control the content of the mRNA transcripts that carry the instructions for building proteins.

Each mRNA transcript contains coding regions, known as exons, and noncoding regions, known as introns. They also include sites that act as signals for where splicing should occur, allowing the cell to assemble the correct sequence for a desired protein. This process enables a single gene to produce multiple proteins; over evolutionary timescales, splicing can also change the size and content of genes and proteins, when different exons become included or excluded.

The spliceosome, which forms on introns, is composed of proteins and noncoding RNAs called small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs). In the first step of spliceosome assembly, an snRNA molecule known as U1 snRNA binds to the 5’ splice site at the beginning of the intron. Until now, it had been thought that the binding strength between the 5’ splice site and the U1 snRNA was the most important determinant of whether an intron would be spliced out of the mRNA transcript.

In the new study, the MIT team discovered that a family of proteins called LUC7 also helps to determine whether splicing will occur, but only for a subset of introns — in human cells, up to 50 percent.

Before this study, it was known that LUC7 proteins associate with U1 snRNA, but the exact function wasn’t clear. There are three different LUC7 proteins in human cells, and Kenny’s experiments revealed that two of these proteins interact specifically with one type of 5’ splice site, which the researchers called “right-handed.” A third human LUC7 protein interacts with a different type, which the researchers call “left-handed.”

The researchers found that about half of human introns contain a right- or left-handed site, while the other half do not appear to be controlled by interaction with LUC7 proteins. This type of control appears to add another layer of regulation that helps remove specific introns more efficiently, the researchers say.

“The paper shows that these two different 5’ splice site subclasses exist and can be regulated independently of one another,” Kenny says. “Some of these core splicing processes are actually more complex than we previously appreciated, which warrants more careful examination of what we believe to be true about these highly conserved molecular processes.”

“Complex splicing machinery”

Previous work has shown that mutation or deletion of one of the LUC7 proteins that bind to right-handed splice sites is linked to blood cancers, including about 10 percent of acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs). In this study, the researchers found that AMLs that lost a copy of the LUC7L2 gene have inefficient splicing of right-handed splice sites. These cancers also developed the same type of altered metabolism seen in earlier work.

“Understanding how the loss of this LUC7 protein in some AMLs alters splicing could help in the design of therapies that exploit these splicing differences to treat AML,” Burge says. “There are also small molecule drugs for other diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy that stabilize the interaction between U1 snRNA and specific 5’ splice sites. So the knowledge that particular LUC7 proteins influence these interactions at specific splice sites could aid in improving the specificity of this class of small molecules.”

Working with a lab led by Sascha Laubinger, a professor at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, the researchers found that introns in plants also have right- and left-handed 5’ splice sites that are regulated by Luc7 proteins.

The researchers’ analysis suggests that this type of splicing arose in a common ancestor of plants, animals, and fungi, but it was lost from fungi soon after they diverged from plants and animals.

“A lot what we know about how splicing works and what are the core components actually comes from relatively old yeast genetics work,” Kenny says. “What we see is that humans and plants tend to have more complex splicing machinery, with additional components that can regulate different introns independently.”

The researchers now plan to further analyze the structures formed by the interactions of Luc7 proteins with mRNA and the rest of the spliceosome, which could help them figure out in more detail how different forms of Luc7 bind to different 5’ splice sites.

###

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the German Research Foundation.

END

Biologists discover a new type of control over RNA splicing

They identified proteins that influence splicing of about half of all human introns, allowing for more complex types of gene regulation.

2025-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Surprising finding for acid reducing drugs

2025-02-20

Acid reducing medicines from the group of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are best-selling drugs that prevent and alleviate stomach problems. PPIs are activated in the acid-producing cells of the stomach, where they block acid production. Researchers at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) made the surprising discovery that zinc-carrying proteins, which are found in all cells, can also activate PPIs – without the presence of gastric acid. The result could be a key to understanding the side effects of PPIs.

Excessive gastric acid can cause not only heartburn, but also chronic complaints such as gastritis or even a stomach ...

Pushing the limits of ‘custom-made’ microscopy

2025-02-20

A new paper updates an EMBL technology advance even further. More details about the original technology can be found in our initial reporting here.

EMBL tech developers have made an important leap forward with a novel methodology that adds an important microscopy capability to life scientists’ toolbox. The advance represents a 1,000-fold improvement in speed and throughput in Brillouin microscopy and provides a way to view light-sensitive organisms more efficiently.

“We were on a quest to speed up image acquisition,” said Carlo Bevilacqua, lead author on ...

Deep Nanometry reveals hidden nanoparticles

2025-02-20

Researchers including those from the University of Tokyo developed Deep Nanometry, an analytical technique combining advanced optical equipment with a noise removal algorithm based on unsupervised deep learning. Deep Nanometry can analyze nanoparticles in medical samples at high speed, making it possible to accurately detect even trace amounts of rare particles. This has proven its potential for detecting extracellular vesicles indicating early signs of colon cancer, and it is hoped that it can be applied to other medical and industrial fields.

Did you know your ...

Screen time linked to bipolar and manic symptoms in U.S. preteens

2025-02-20

Toronto, ON - Preteens who spend more time on screens are more likely to develop manic symptoms years two-years later, according to a new study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

The findings reveal that 10- to 11-year-olds who engage heavily with social media, video games, texting, and videos show a greater risk of symptoms such as inflated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, rapid speech, racing thoughts, and impulsivity — behaviors characteristic of manic episodes, a key feature of bipolar-spectrum disorders.

“Adolescence is a particularly ...

In ancient stellar nurseries, some stars are born of fluffy clouds

2025-02-20

Fukuoka, Japan—How are stars born, and has it always been this way?

Stars form in regions of space known as stellar nurseries, where high concentrations of gas and dust coalesce to form a baby star. Also called molecular clouds, these regions of space can be massive, spanning hundreds of light-years and forming thousands of stars. And while we know much about the life cycle of a star thanks to advances in technology and observational tools, precise details remain obscure. For example, did stars form this way in the early universe?

Publishing in The Astrophysical Journal, researchers from Kyushu University, in collaboration with Osaka Metropolitan ...

Blood pressure drug could be a safer alternative for treating ADHD symptoms, finds study

2025-02-20

Blood pressure drug could be a safer alternative for treating ADHD symptoms, finds study

Repurposing amlodipine, a commonly used blood pressure medicine, could help manage attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, according to an international study involving the University of Surrey.

In a study published in Neuropsychopharmacology, researchers tested five potential drugs in rats bred to exhibit ADHD-like symptoms. Among them, only amlodipine, a common blood pressure medication, significantly reduced hyperactivity.

To ...

Daily cannabis use linked to public health burden

2025-02-20

WASHINGTON (Feb. 20, 2025)--A new study analyzes the disease burden and the risk factors for severity among people who suffer from a condition called cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Researchers at the George Washington University say the condition occurs in people who are long-term regular consumers of cannabis and causes nausea, uncontrollable vomiting and excruciating pain in a cyclical pattern that often leads to repeated trips to the hospital.

“This is one of the first large studies to examine the burden of disease associated with this cannabis-linked syndrome,” says Andrew Meltzer, professor of emergency medicine ...

A new gene identified in the search for a therapy to treat malignant cardiac arrythmia

2025-02-20

Cardiac arrhythmias affect millions across the world and are responsible for a fifth of all deaths in the Netherlands. Currently there are multiple treatment options, ranging from life-long medication to invasive surgical procedures. Research from Amsterdam UMC and Johns Hopkins University, published today in the European Heart Journal, sets another important step in the hunt for a one-off gene therapy that could improve heart function and protect against arrhythmias.

"Arrhythmias often occur due to slowing of conduction of the electrical impulse through the heart. Rapid impulse conduction is needed for ...

‘Fog harvesting’ could yield water for drinking and agriculture in the world’s driest regions

2025-02-20

With less annual rainfall than 1 mm per year, Chile’s Atacama Desert is one of the driest places in the world. The main water source of cities in the region are underground rock layers that contain water-filled pore spaces which last recharged between 17,000 and 10,000 years ago.

Now, local researchers have assessed if ‘fog harvesting,’ a method where fog water is collected and saved, is a feasible way to provide the residents of informal settlements with much needed water.

“This research represents a notable shift in the ...

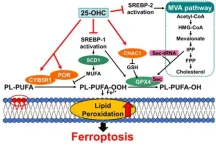

Unveiling the intricate mechanisms behind oxysterol-induced cell death

2025-02-20

Oxysterols are a class of molecules derived from cholesterol via oxidation or as byproducts of cholesterol synthesis. Despite their relatively low concentration within our bodies, oxysterols are known to play many important biological roles, acting as transcriptional regulators, precursors for bile acid, and key players in brain development.

On the flip side, some pathologies are associated with imbalances in oxysterols. In particular, 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-OHC) has been shown to contribute to arteriosclerosis, cancer development, central nervous system ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

Same-day hospital discharge is safe in selected patients after TAVI

Why do people living at high altitudes have better glucose control? The answer was in plain sight

Red blood cells soak up sugar at high altitude, protecting against diabetes

A new electrolyte points to stronger, safer batteries

Environment: Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

Targeted radiation therapy improves quality of life outcomes for patients with multiple brain metastases

Cardiovascular events in women with prior cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Transplantation and employment earnings in kidney transplant recipients

Brain organoids can be trained to solve a goal-directed task

Treatment can protect extremely premature babies from lung disease

Roberto Morandotti wins prestigious Max Born Award for pioneering research in quantum photonics

Scientists map brain's blood pressure control center

Acute coronary events registry provides insights into sex-specific differences

Bar-Ilan University and NVIDIA researchers improve AI’s ability to understand spatial instructions

New single-cell transcriptomic clock reveals intrinsic and systemic T cell aging in COVID-19 and HIV

Smaller fish and changing food webs – even where species numbers stay the same

Missed opportunity to protect pregnant women and newborns: Study shows low vaccination rates among expectant mothers in Norway against COVID-19 and influenza

Emotional memory region of aged brain is sensitive to processed foods

Neighborhood factors may lead to increased COPD-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations

Food insecurity impacts employees’ productivity

Prenatal infection increases risk of heavy drinking later in life

‘The munchies’ are real and could benefit those with no appetite

FAU researchers discover novel bacteria in Florida’s stranded pygmy sperm whales

DEGU debuts with better AI predictions and explanations

‘Giant superatoms’ unlock a new toolbox for quantum computers

Jeonbuk National University researchers explore metal oxide electrodes as a new frontier in electrochemical microplastic detection

Cannabis: What is the profile of adults at low risk of dependence?

Medical and materials innovations of two women engineers recognized by Sony and Nature

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

[Press-News.org] Biologists discover a new type of control over RNA splicingThey identified proteins that influence splicing of about half of all human introns, allowing for more complex types of gene regulation.