(Press-News.org) When Jeff Kneebone was a college student in 2002, his research involved a marine mystery that has stumped curious scientists for the last two decades. That mystery had to do with thorny skates in the North Atlantic. In some parts of their range, individuals of this species come in two distinct sizes, irrespective of sex, and no one could figure out why. At the time, neither could Kneebone.

In a new study, Kneebone and researchers from the Florida Museum of Natural History say they’ve finally found an answer. And it’s all thanks to COVID-19.

People have known about the size discrepancy in thorny skates for nearly a century, but it became critically important beginning in the 1970s, when their numbers took a nosedive. The cause of the decline was thought to be overfishing by humans, and the solution was simple. In 2003, a strict fishing moratorium in the United States was put in place for thorny skates and another species, the barndoor skate, that was also doing poorly.

“The barndoor skate rebounded to the point where they’re now allowed to be harvested again, but for whatever reason, the thorny skate has remained low, despite 20 years of protection,” said Kneebone, who currently works as a senior scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

According to survey data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, thorny skates have declined by 80% to 95% in some areas, particularly the Gulf of Maine, and they’re also languishing in low numbers in Canadian waters off the Scotian Shelf.

Thorny skates have a large distribution. They can be found from South Carolina up to the Arctic Circle and east through Scotland, Norway and Russia. In the Arctic and European part of their range, thorny skates come in just one size. It’s only along the coast of North America that small and large varieties coexist.

“No one could understand what the deal was with these skates,” said study co-author Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Scientists had tried studying thorny skate DNA to see if there were any differences between the large and small sizes, but they came up empty-handed. “The big forms are twice the size, and it takes them 11 years to reach adulthood. The small forms are mature by the time they’re six years old. There’s got to be genetic differences.”

Naylor thought he might be able to crack the code.

The idea was simple. Previous studies had tried to answer the question by analyzing a few short DNA sequences taken from a small number of thorny skates. It was a good strategy, Naylor reasoned, but fell short because researchers hadn’t yet processed nearly enough DNA. Instead, what was needed was a gene capture approach: a labor-intensive method that allows researchers to collect DNA sequence data from thousands of sequences throughout an organism’s genome, the term used to describe DNA stored in the nuclei of cells. Most importantly, they’d do this for hundreds of thorny skates, which would provide them ample data to scour.

He put the word out to the scientific community, and people sent the team more than 600 tissue samples collected across much of the Northern Hemisphere, and he made the costly preparations to get the lab work underway, with funding from the Lenfest Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the subsequent restrictions that were put in place made it impossible to conduct extensive, in-person lab work, putting the project on indefinite hiatus.

One of Naylor’s postdoctoral researchers at the time, Shannon Corrigan, pulled together a salvage mission. If they couldn’t collect gene capture DNA from hundreds of thorny skates, they could sequence the entire genome of four or five individuals. This would drastically cut down on the amount of in-person work that needed to be done.

It was a risky plan. There was only a small chance they would find what they were looking for by sequencing genomes, and they only had enough funding to do one or the other.

It was a Hail Mary, Naylor said, but one that paid off. Had they used the original gene capture idea, “we would have missed it entirely.”

As it was, they only nearly missed it. The study’s first author, Pierre Lesturgie, was tasked with analyzing the genome — all 2.5 billion base pairs of it — once it had been sequenced. As he was combing through the data, something strange caught his eye.

“There was a large region on chromosome two that we thought was weird. Since it was behaving in a way we didn’t understand, we considered removing it from the analysis,” Lesturgie said. He thought it might be an aberration or potentially an error introduced during the sequencing process, and worried it would reduce the accuracy of their results. He was about to trash it when Naylor mentioned it looked like the sort of thing you’d get from a gene inversion, a natural process in which a sequence of DNA is flipped in the wrong direction.

Most organisms, including humans, have at least a few inversions in their genomes, so they’re not uncommon, but they seldom result in observable differences between individuals. But because it was all the researchers had to go on, they checked to see if the inverted sequence was present in both large and small thorny skates. It wasn’t. Only large thorny skates had the mirrored stretch of DNA. They’d need to do more work to confirm it, but they’d found their answer. Cue the popping bottles of champagne and celebratory good cheer.

Figuring out what caused the size difference is only the first step, Kneebone said. Now researchers can make headway on developing a conservation plan. The next step will involve good old-fashioned observation. Before the discovery of the gene inversion, it was difficult — and in some cases impossible — to distinguish between the large and small types.

“We could identify the large males and females, because they’re bigger than anything else,” Naylor said. At maturity, both large and small males develop long, trailing claspers on either side of their tale, giving them the overall appearance of a kite with streamers. “So when you’ve got a small male with large claspers, we know it’s an adult. But we can’t do anything with the small females, because we don’t know whether they’re just babies on their way to getting big.”

This limitation has hampered research on the species, Kneebone said. “The big question has always been, what do the life histories of the two morphs look like? Currently, they’re not discriminated in the stock assessment, so a thorny skate is a thorny skate is a thorny skate.”

The final step will be figuring out why thorny skates are continuing to decline in parts of their range. Fortunately, scientists already have a few good leads. Current evidence suggests it’s harder for the two sizes to interbreed in places where they’re declining than it is in others. It’s possible this natural and partial barrier to reproduction cold be exacerbated by climate change.

Thorny skates are having the most trouble in the Gulf of Maine, where sea surface temperatures have increased faster than 99% of the world’s oceans over the last several years. This has had all sorts of unpleasant effects, like the collapse of cod fisheries in the region.

Whether climate change is partially responsible for the plight of the thorny skate and, if so, why it has an undue negative influence on this single species compared with other skates that live in the same area, remains to be seen. To determine that, Kneebone said they’ll need more data.

“We’re trying to use the best available science to make decisions about how to best manage and sustain populations.”

The authors published their study in the journal Nature Communications.

END

Thorny skates come in snack and party sizes. After a century of guessing, scientists now know why.

2025-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

When did human language emerge?

2025-03-18

It is a deep question, from deep in our history: When did human language as we know it emerge? A new survey of genomic evidence suggests our unique language capacity was present at least 135,000 years ago. Subsequently, language might have entered social use 100,000 years ago.

Our species, Homo sapiens, is about 230,000 years old. Estimates of when language originated vary widely, based on different forms of evidence, from fossils to cultural artifacts. The authors of the new analysis took a different approach. ...

Meteorites: A geologic map of the asteroid belt

2025-03-18

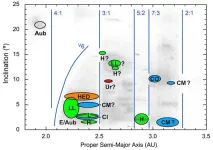

March 18, 2025, Mountain View, CA -- Where do meteorites of different type come from? In a review paper in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, published online this week, astronomers trace the impact orbit of observed meteorite falls to several previously unidentified source regions in the asteroid belt.

“This has been a decade-long detective story, with each recorded meteorite fall providing a new clue,” said meteor astronomer and lead author Peter Jenniskens of the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center. “We now have the first outlines of a geologic map of the asteroid belt.”

Ten years ago, ...

Study confirms safety and efficacy of higher-dose-per-day radiation for early-stage prostate cancer

2025-03-18

A new large-scale study co-led by UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center investigators provides the strongest evidence yet that a shorter, standard-dose course radiation treatment is just as effective as conventional radiotherapy for prostate cancer, without compromising the safety of patients.

The shorter approach, known as isodose moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHFRT), delivers slightly higher doses of radiation per session, allowing the total treatment duration to be over four to five weeks instead of seven to eight weeks.

According to the study, patients who received this type ...

Virginia Tech researchers publish revolutionary blueprint to fuse wireless technologies and AI

2025-03-18

There’s a major difference between humans and current artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities: common sense. According to a new visionary paper by Walid Saad, professor in the College of Engineering and the Next-G Wireless Lead at the Virginia Tech Innovation Campus, a true revolution in wireless technologies is only possible through endowing the system with the next generation of AI that can think, imagine, and plan akin to humans.

Published in the Proceedings of the IEEE Journal's Special Issue on the Road to 6G with Ph.D. student Omar Hashash and postdoctoral associate Christo Thomas, the paper's findings suggest:

The missing link in the wireless revolution is ...

Illinois study: Extreme heat impacts dairy production, small farms most vulnerable

2025-03-18

URBANA, Ill. – Livestock agriculture is bearing the cost of extreme weather events. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign explores how heat stress affects U.S. dairy production, finding that high heat and humidity lead to a 1% decline in annual milk yield. Small farms are hit harder than large farms, which may be able to mitigate some of the effects through management strategies.

“Cows are mammals like us, and they experience heat stress just like we do. When cows are exposed to extreme heat, it can have a range of negative physical effects. There is an increased risk of infection, restlessness, and decreased ...

Continuous glucose monitors can optimize diabetic ketoacidosis management

2025-03-18

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a common severe complication of diabetes, which develops when the body can’t produce enough insulin.

During DKA the body starts breaking down fat, causing a buildup of acids in the bloodstream. The symptoms often include thirst, weakness, nausea and confusion.

Concerningly, this condition accounts for more than 500,000 hospital days per year, often in the intensive care unit, with an estimated cost of $2.4 billion.

In a study, published in CHEST Critical Care, University of Michigan researchers show that using continuous glucose monitors can help measure glucose accurately during DKA and ...

Time is not the driving influence of forest carbon storage, U-M study finds

2025-03-18

Figures and photos

It is commonly assumed that as forest ecosystems age, they accumulate and store, or "sequester," more carbon.

A new study based at the University of Michigan Biological Station untangled carbon cycling over two centuries and found that it's more nuanced than that.

The synergistic effects of forest structure, the composition of the tree and fungal communities, and soil biogeochemical processes have more influence on how much carbon is being sequestered above and below ground than previously thought.

The ...

Adopting zero-emission trucks and buses could save lives, prevent asthma in Illinois

2025-03-18

Guided by the lived experiences of community partners, Northwestern University scientists have simulated the effects of zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) adoption on future air quality for the greater Chicago area.

The results were published today (March 18) in the journal Frontiers of Earth Science.

Motivated by California’s Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) policy, Neighbors for an Equitable Transition to Zero-Emissions (NET-Z) Illinois members partnered with Northwestern researchers to explore how a similar strategy might play out in Cook County and the surrounding areas.

To develop a model that more realistically simulates ...

New fossil discovery reveals how volcanic deposits can preserve the microscopic details of animal tissues

2025-03-18

An analysis of a 30,000-year-old fossil vulture from Central Italy has revealed for the first time that volcanic rock can preserve microscopic details in feathers - the first ever record of such a preservation.

An international team, led by Dr Valentina Rossi (University College Cork, Ireland), discovered a new mode of preservation of soft tissues that can occur when animals are buried in ash-rich volcanic sediments.

The new research, published in the scientific journal Geology, reveals that the feathers ...

New chromosome barcode system unveils genetic secrets of alfalfa

2025-03-18

In a recent study, scientists have developed a revolutionary chromosome identification system for alfalfa, one of the world's most economically vital forage crops. Leveraging an advanced Oligo-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) barcode technique, researchers successfully mapped and identified all chromosomes in alfalfa, uncovering unexpected chromosomal anomalies, including aneuploidy and large segment deletions. This breakthrough not only enhances molecular cytogenetics but also sheds light on the genetic stability ...