Next time you cross a crowded plaza, crosswalk, or airport concourse, take note of the pedestrian flow. Are people walking in orderly lanes, single-file, to their respective destinations? Or is it a haphazard tangle of personal trajectories, as people dodge and weave through the crowd?

MIT instructor Karol Bacik and his colleagues studied the flow of human crowds and developed a first-of-its-kind way to predict when pedestrian paths will transition from orderly to entangled. Their findings may help inform the design of public spaces that promote safe and efficient thoroughfares.

In a paper appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers consider a common scenario in which pedestrians navigate a busy crosswalk. The team analyzed the scenario through mathematical analysis and simulations, considering the many angles at which individuals may cross and the dodging maneuvers they may make as they attempt to reach their destinations while avoiding bumping into other pedestrians along the way.

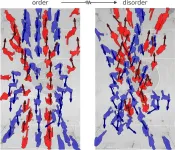

The researchers also carried out controlled crowd experiments and studied how real participants walked through a crowd to reach certain locations. Through their mathematical and experimental work, the team identified a key measure that determines whether pedestrian traffic is ordered, such that clear lanes form in the flow, or disordered, in which there are no discernible paths through the crowd. Called “angular spread,” this parameter describes the number of people walking in different directions.

If a crowd has a relatively small angular spread, this means that most pedestrians walk in opposite directions and meet the oncoming traffic head-on, such as in a crosswalk. In this case, more orderly, lane-like traffic is likely. If, however, a crowd has a larger angular spread, such as in a concourse, it means there are many more directions that pedestrians can take to cross, with more chance for disorder.

In fact, the researchers calculated the point at which a moving crowd can transition from order to disorder. That point, they found, was an angular spread of around 13 degrees, meaning that if pedestrians don’t walk straight across, but instead an average pedestrian veers off at an angle larger than 13 degrees, this can tip a crowd into disordered flow.

“This all is very commonsense,” says Bacik, who is a instructor of applied mathematics at MIT. “The question is whether we can tackle it precisely and mathematically, and where the transition is. Now we have a way to quantify when to expect lanes — this spontaneous, organized, safe flow — versus disordered, less efficient, potentially more dangerous flow.”

The study’s co-authors include Grzegorz Sobota and Bogdan Bacik of the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland, and Tim Rogers at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom.

Right, left, center

Bacik, who is trained in fluid dynamics and granular flow, came to study pedestrian flow during 2021, when he and his collaborators looked into the impacts of social distancing, and ways in which people might walk among each other while maintaining safe distances. That work inspired them to look more generally into the dynamics of crowd flow.

In 2023, he and his collaborators explored “lane formation,” a phenomenon by which particles, grains, and, yes, people have been observed to spontaneously form lanes, moving in single-file when forced to cross a region from two opposite directions. In that work, the team identified the mechanism by which such lanes form, which Bacik sums up as “an imbalance of turning left versus right.” Essentially, they found that as soon as something in a crowd starts to look like a lane, individuals around that fledgling lane either join up, or are forced to either side of it, walking parallel to the original lane, which others can follow. In this way, a crowd can spontaneously organize into regular, structured lanes.

“Now we’re asking, how robust is this mechanism?” Bacik says. “Does it only work in this very idealized situation, or can lane formation tolerate some imperfections, such as some people not going perfectly straight, as they might do in a crowd?”

Lane change

For their new study, the team looked to identify a key transition in crowd flow: When do pedestrians switch from orderly, lane-like traffic, to less organized, messy flow? The researchers first probed the question mathematically, with an equation that is typically used to describe fluid flow, in terms of the average motion of many individual molecules.

“If you think about the whole crowd flowing, rather than individuals, you can use fluid-like descriptions,” Bacik explains. “It’s this art of averaging, where, even if some people may cross more assertively than others, these effects are likely to average out in a sufficiently large crowd. If you only care about the global characteristics like, are there lanes or not, then you can make predictions without detailed knowledge of everyone in the crowd.”

Bacik and his colleagues used equations of fluid flow, and applied them to the scenario of pedestrians flowing across a crosswalk. The team tweaked certain parameters in the equation, such as the width of the fluid channel (in this case, the crosswalk), and the angle at which molecules (or people) flowed across, along with various directions that people can “dodge,” or move around each other to avoid colliding.

Based on these calculations, the researchers found that pedestrians in a crosswalk are more likely to form lanes, when they walk relatively straight across, from opposite directions. This order largely holds until people start veering across at more extreme angles. Then, the equation predicts that the pedestrian flow is likely to be disordered, with few to no lanes forming.

The researchers were curious to see whether the math bears out in reality. For this, they carried out experiments in a gymnasium, where they recorded the movements of pedestrians using an overhead camera. Each volunteer wore a paper hat, depicting a unique barcode that the overhead camera could track.

In their experiments, the team assigned volunteers various start and end positions along opposite sides of a simulated crosswalk, and tasked them with simultaneously walking across the crosswalk to their target location without bumping into anyone. They repeated the experiment many times, each time having volunteers assume different start and end positions. In the end, the researchers were able to gather visual data of multiple crowd flows, with pedestrians taking many different crossing angles.

When they analyzed the data and noted when lanes spontaneously formed, and when they did not, the team found that, much like the equation predicted, the angular spread mattered. Their experiments confirmed that the transition from ordered to disordered flow occurred somewhere around the theoretically predicted 13 degrees. That is, if an average person veered more than 13 degrees away from straight ahead, the pedestrian flow could tip into disorder, with little lane formation. What’s more, they found that the more disorder there is in a crowd, the less efficiently it moves.

The team plans to test their predictions on real-world crowds and pedestrian thoroughfares.

“We would like to analyze footage and compare that with our theory,” Bacik says. “And we can imagine that, for anyone designing a public space, if they want to have a safe and efficient pedestrian flow, our work could provide a simpler guideline, or some rules of thumb.”

This work is supported, in part, by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of UK Research and Innovation.

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News

END