(Press-News.org) A multidisciplinary clinical team led by Professor Bernat Soria from the Institute of Bioengineering at the Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH, Spain) has developed a new method to deliver cell therapies in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a life support system used in cases of severe lung failure. The advance has been published in Stem Cell Research & Therapy (Springer Nature Group). The team has opted not to patent the technique in order to encourage its use in public health systems once further clinical testing is completed.

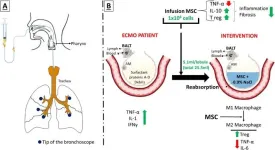

The method—named CIBA, for Consecutive Intrabronchial Administration—enables the delivery of stem-cell-based treatments directly into the alveoli of critically ill patients who cannot receive standard intravenous cell therapy due to the ECMO system's constraints.

Until now, cell therapies were nearly impossible to administer to ECMO patients, as intravenous infusion risked clogging the system's gas-exchange membranes. The CIBA method solves this technical barrier through controlled, fractionated intrabronchial delivery, depositing the therapeutic cells precisely where needed without interfering with the ECMO circuit.

"What we've achieved," explains Prof. Soria, "is a safe way to deliver regenerative therapies when all other options are blocked. Imagine watering a fragile plant, but the watering can would flood it. CIBA allows us to drip-feed the therapy gently and exactly where it's needed—right into the lungs."

A first-of-its-kind administration in pediatric ECMO

The method was first applied under compassionate use in a 2-year-old patient with end-stage interstitial lung disease and no possibility of lung transplantation. Despite multiple immunosuppressive treatments and over three months of ECMO support, the child's condition remained critical.

With authorization from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS), a single dose of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (WJ-MSCs) was administered intrabronchially using the CIBA method. The procedure was well tolerated, and the patient was successfully extubated within 72 hours. However, weeks later, his condition deteriorated again, and ECMO support was withdrawn after 127 days, in agreement with his family.

"CIBA did not cure the underlying disease," says Prof. Soria, "but it demonstrated, for the first time, that cell therapies can be delivered safely in ECMO patients. That's a breakthrough. We now have a new therapeutic door to open."

How does it work?

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), which can be sourced from the umbilical cord, bone marrow, adipose tissue, or dental pulp, are not yet specialized and can migrate to damaged tissue, modulate inflammation, and promote regeneration. Once in the lungs, these cells interact with immune cells like alveolar macrophages, releasing anti-inflammatory signals that help prevent tissue damage and support healing.

This new route of administration avoids systemic circulation and targets the lungs directly, maximizing therapeutic effect and minimizing risk. The team notes that higher doses or repeated administrations could be explored in future trials.

A national collaboration committed to open science

This proof-of-concept study is part of the DECODE clinical project, funded by Spain's Instituto de Salud Carlos III. It involved 28 clinicians from four national institutions: Hospital 12 de Octubre (Madrid), Banc de Sang i Teixits (Catalonia), the Institute of Bioengineering at UMH (Elche), and the Institute for Health and Biomedical Research of Alicante (ISABIAL).

"Advanced therapies are already expensive enough," states Prof. Soria. "We chose not to patent this technique because it should reach patients without adding more cost. We're committed to public science with direct clinical impact."

END

New method to deliver cell therapies in critically ill patients on external lung support

Novel intrabronchial method allows safe delivery of stem cells directly into the lungs of ECMO-supported patients. The technique has not been patented to promote open clinical use and wider patient access

2025-04-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Climate-related trauma can have lasting effects on decision-making, study finds

2025-04-16

A new study from University of California San Diego suggests that climate trauma — such as experiencing a devastating wildfire — can have lasting effects on cognitive function. The research, which focused on survivors of the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California, found that individuals directly exposed to the disaster had difficulty making decisions that prioritize long-term benefits. The findings were recently published in Scientific Reports, part of the Nature portfolio of journals.

“Our previous research has shown that survivors of California’s 2018 Camp Fire experience prolonged symptoms ...

Your cells can hear

2025-04-16

Kyoto, Japan -- There's a sensation that you experience -- near a plane taking off or a speaker bank at a concert -- from a sound so total that you feel it in your very being. When this happens, not only do your brain and ears perceive it, but your cells may also.

Technically speaking, sound is a simple phenomenon, consisting of compressional mechanical waves transmitted through substances, which exists universally in the non-equilibrated material world. Sound is also a vital source of environmental information for living beings, while its capacity to induce physiological responses at the cell ...

Farm robot autonomously navigates, harvests among raised beds

2025-04-16

Strawberry fields forever will exist for the in-demand fruit, but the laborers who do the backbreaking work of harvesting them might continue to dwindle. While raised, high-bed cultivation somewhat eases the manual labor, the need for robots to help harvest strawberries, tomatoes, and other such produce is apparent.

As a first step, Osaka Metropolitan University Assistant Professor Takuya Fujinaga has developed an algorithm for robots to autonomously drive in two modes: moving to a pre-designated destination and moving alongside ...

The bear in the (court)room: who decides on removing grizzly bears from the endangered species list?

2025-04-16

By Dr Kelly Dunning

The Endangered Species Act (ESA), now 50 years old, was once a rare beacon of bipartisan unity, signed into law by President Richard Nixon with near-unanimous political support. Its purpose was clear: protect imperiled species and enable their recovery using the best available science to do so. Yet, as our case study on the grizzly bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem reveals, wildlife management under the ESA has changed, becoming a political battleground where science is increasingly drowned out by partisan ideology, bureaucratic delays, power struggles, and competing political interests. ...

First study reveals neurotoxic potential of rose-scented citronellol at high exposure levels

2025-04-16

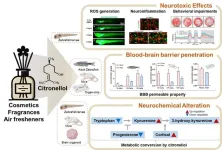

Citronellol, a rose-scented compound commonly found in cosmetics and household products, has long been considered safe. However, a Korean research team has, for the first time, identified its potential to cause neurotoxicity when excessively exposed.

A collaborative research team led by Dr. Myung Ae Bae at the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT) and Professors Hae-Chul Park and Suhyun Kim at Korea University has discovered that high concentrations of citronellol can trigger neurological and behavioral toxicity. The study, published in the Journal ...

For a while, crocodile

2025-04-16

Most people think of crocodylians as living fossils— stubbornly unchanged, prehistoric relics that have ruled the world’s swampiest corners for millions of years. But their evolutionary history tells a different story, according to new research led by the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) and the University of Utah.

Crocodylians are surviving members of a 230-million-year lineage called crocodylomorphs, a group that includes living crocodylians (i.e. crocodiles, alligators and gharials) and their many extinct ...

Scientists find evidence that overturns theories of the origin of water on Earth

2025-04-16

Images available via link in the notes section

University of Oxford researchers have helped overturn the popular theory that water on Earth originated from asteroids bombarding its surface;

Scientists have analysed a meteorite analogous to the early Earth to understand the origin of hydrogen on our planet.

The research team demonstrated that the material which built our planet was far richer in hydrogen than previously thought.

The findings, which support the theory that the formation of habitable conditions on Earth did not rely on asteroids ...

Foraging on the wing: How can ecologically similar birds live together?

2025-04-16

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A spat between birds at your backyard birdfeeder highlights the sometimes fierce competition for resources that animals face in the natural world, but some ecologically similar species appear to coexist peacefully. A classic study in songbirds by Robert MacArthur, one of the founders of modern ecology, suggested that similar wood warblers — insect-eating, colorful forest songbirds — can live in the same trees because they actually occupy slightly different locations in the tree and presumably eat different insects. Now, a new study is using modern techniques to revisit MacArthur’s ...

Little birds’ personalities shine through their song – and may help find a mate

2025-04-16

In birds, singing behaviours play a critical role in mating and territory defence.

Although birdsong can signal individual quality and personality, very few studies have explored the relationship between individual personality and song complexity, and none has investigated this in females, say Flinders University animal behaviour experts.

They have examined the relationships between song complexity and two personality traits (exploration and aggressiveness) in wild superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) in Australia, a species in which both sexes learn to produce complex songs.

“Regardless of their sex ...

Primate mothers display different bereavement response to humans

2025-04-16

Macaque mothers experience a short period of physical restlessness after the death of an infant, but do not show typical human signs of grief, such as lethargy and appetite loss, finds a new study by UCL anthropologists.

Published in Biology Letters, the researchers found that bereaved macaque mothers spent less time resting (sleep, restful posture, relaxing) than the non-bereaved females in the first two weeks after their infants’ deaths.

Researchers believe this physical restlessness could represent an initial period of ‘protest’ among the bereaved macaque mothers, similar ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] New method to deliver cell therapies in critically ill patients on external lung supportNovel intrabronchial method allows safe delivery of stem cells directly into the lungs of ECMO-supported patients. The technique has not been patented to promote open clinical use and wider patient access