GW researchers reveal first autism candidate gene that demonstrates sensitivity to sex hormones

2011-02-17

(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON— George Washington University researcher, Dr. Valerie Hu, Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and her team at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, have found that male and female sex hormones regulate expression of an important gene in neuronal cell culture through a mechanism that could explain not only higher levels of testosterone observed in some individuals with autism, but also why males have a higher incidence of autism than females.

The gene, RORA, encodes a protein that works as a "master switch" for gene expression, and is critical in the development of the cerebellum as well as in many other processes that are impaired in autism. Dr. Hu's earlier research found that RORA was decreased in the autistic brain. In this study, the research group demonstrates that aromatase, a protein which is regulated by RORA, is also reduced in autistic brains. This is significant because aromatase converts testosterone to estrogen. Thus, a decrease in aromatase is expected to lead in part to build up of male hormones which, in turn, further decrease RORA expression, as demonstrated in this study using a neuronal cell model. On the other hand, female hormones were found to increase RORA in the neuronal cells. The researchers believe that females may be more protected against RORA deficiency not only because of the positive effect of estrogen on RORA expression, but also because estrogen receptors, which regulate some of the same genes as RORA, can help make up for the deficiency in RORA.

"It is well known that males have a higher tendency for autism than females; however, this new research may, for the first time, provide a molecular explanation for why and how this happens. This is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of understanding some of the biology underlying autism, and we will continue our work to discover new ways to understand and, hopefully, to someday combat this neurodevelopmental disorder," said Dr. Hu.

In her research published in 2009, Dr. Hu and colleagues found that RORA deficiencies were only apparent in the most severe cases of autism and were observed in the brain tissues of both male and female subjects. They further found that the deficiency in RORA was linked to a chemical modification of the gene (called methylation) which effectively reduces the level of RORA.

INFORMATION:

About The George Washington University Medical Center

The George Washington University Medical Center is an internationally recognized interdisciplinary academic health center that has consistently provided high-quality medical care in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area since 1824. The Medical Center comprises the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, the 11th oldest medical school in the country; the School of Public Health and Health Services, the only such school in the nation's capital; GW School of Nursing; GW Hospital, and The GW Medical Faculty Associates. For more information on GWUMC, visit www.gwumc.edu.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011-02-17

New fossil discoveries have provided a glimpse into the biogeographic configuration of Africa over the last seven million years.

Modern-day Africa south of the Sahara is home to a unique variety of mammals, a great number of which are not found anywhere else in the world. Biogeographers have long recognized that sub-Saharan Africa constitutes one of the world's six major mammalian biogeographic divisions, termed 'realms'. However, the historical development of these continental regions of biogeographic diversity has been little explored.

Description of six million-year-old ...

2011-02-17

"Too simple" and "not so fast" suggest biological anthropologists from the George Washington University and New York University about the origins of human ancestry. In the upcoming issue of the journal Nature, the anthropologists question the claims that several prominent fossil discoveries made in the last decade are our human ancestors. Instead, the authors offer a more nuanced explanation of the fossils' place in the Tree of Life. They conclude that instead of being our ancestors the fossils more likely belong to extinct distant cousins.

"Don't get me wrong, these ...

2011-02-17

When doctors discover high concentrations of regulatory T cells in the tumors of breast cancer patients, the prognosis is often grim, though why exactly has long been unclear.

Now new research at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine suggests these regulatory T cells, whose job is to help mediate the body's immune response, produce a protein that appears to hasten and intensify the spread of breast cancer to distant organs and, in doing so, dramatically increase the risk of death.

The findings are reported in the Feb. 16 advance online edition ...

2011-02-17

It has been long known that stress plays a part not just in the graying of hair but in hair loss as well. Over the years, numerous hair-restoration remedies have emerged, ranging from hucksters' "miracle solvents" to legitimate medications such as minoxidil. But even the best of these have shown limited effectiveness.

Now, a team led by researchers from UCLA and the Veterans Administration that was investigating how stress affects gastrointestinal function may have found a chemical compound that induces hair growth by blocking a stress-related hormone associated with ...

2011-02-17

Montreal, February 16, 2011 – Recent studies conducted at the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) on a group of PCSK enzymes could have a positive impact on health, from cholesterol to osteoporosis. A team led by Dr. Nabil G. Seidah, Director of the Biochemical Neuroendocrinology research unit, has published six articles in prestigious scientific journals over the past four months, all shedding light on novel functions of certain PCSK enzymes.

PCSK enzymes belong to the proprotein convertase family, responsible for the conversion of an inactive protein ...

2011-02-17

Researchers from the Department of Neurology at NYU Langone Medical Center identified potential benefits of a new computer application that automatically detects subtle brain lesions in MRI scans in patients with epilepsy. In a study published in the February 2011 issue of PLoS ONE, the authors discuss the software's potential to assist radiologists in better identifying and locating visually undetectable, operable lesions.

"Our method automatically identified abnormal areas in MRI scans in 92 percent of the patients sampled, which were previously identified by expert ...

2011-02-17

LOS ANGELES – Increasing puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, the most abundant brain peptidase in mammals, slowed the damaging accumulation of tau proteins that are toxic to nerve cells and eventually lead to the neurofibrillary tangles, a major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, according to a study published online in the journal, Human Molecular Genetics.

Researchers found they could safely increase the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, PSA/NPEPPS, by two to three times the usual amount in animal models, and it removed the ...

2011-02-17

Children with hip and thigh implants designed to help heal a broken bone or correct other bone conditions are at risk for subsequent fractures of the very bones that the implants were intended to treat, according to new research from Johns Hopkins Children's Center.

Findings of the Johns Hopkins study, based on an analysis of more than 7,500 pediatric bone implants performed at Hopkins over 15 years, will be presented Feb. 16 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Although the absolute risk among the patients was relatively small — nine ...

2011-02-17

Scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute have begun to unravel how blood stem cells regenerate themselves, identifying a key gene required for the process.

The discovery that the Erg gene is vitally important to blood stem cells' unique ability to self-renew could give scientists new opportunities to use blood stem cells for tissue repair, transplantation and other therapeutic applications.

Professor Doug Hilton, Dr Samir Taoudi and colleagues from the institute's Molecular Medicine and Cancer and Haematology divisions led the study. Dr Taoudi said the research ...

2011-02-17

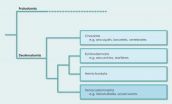

An international team of scientists including Albert Poustka from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin has discovered that Xenoturbellida and the acoelomorph worms, both simple marine worms, are more closely related to complex organisms like humans and sea urchins than was previously assumed. As a result they have made a major revision to the phylogenetic history of animals. Up to now, the acoelomate worms were viewed as the crucial link between simple animals like sponges and jellyfish and more complex organisms. It has now emerged that these animals ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] GW researchers reveal first autism candidate gene that demonstrates sensitivity to sex hormones