Eggs' quality control mechanism explained

2011-02-18

(Press-News.org) To protect the health of future generations, body keeps a careful watch on its precious and limited supply of eggs. That's done through a key quality control process in oocytes (the immature eggs), which ensures elimination of damaged cells before they reach maturity. In a new report in the February 18th Cell, a Cell Press publication, researchers have made progress in unraveling how a factor called p63 initiates the deathblow.

In fact, p63 is a close relative of the infamous tumor suppressor p53, and both proteins recognize DNA damage. Because of this heritage it was initially assumed that p63 would also function as a tumor suppressor, but various forms of the protein are now known to be important in development. One in particular, called TAp63a, is responsible for killing off damaged oocytes.

But it seems that plenty of TAp63a is always around, whether oocytes are damaged or not, suggesting that there must be a very special way that the protein is kept under wraps lest it kill off perfectly good cells. A team lead by Volker Dötsch of Goethe University has figured out how that works.

The quality control factor normally exists in oocytes in inactive pairs or dimers, he explained. When double strand breaks to the DNA occur, those dimers are chemically modified by an as-yet unidentified enzyme, allowing them to open up and join forces with a second open pair. The result is an active tetramer that can bind DNA more effectively, leading to the death of the damaged cells.

That activation of TAp63a cannot be undone, they show, even if you reverse the chemical modification that enabled the tetramer formation in the first place. That irreversibility stems from an extra helix structure that keeps the tetramer stable.

"It's all or nothing," Dötsch said. "Once activated, the path to cell death is decided."

Dötsch believes that this quality control of the genetic integrity of oocytes likely represents the original function of the p53 family, with cell cycle arrest and tumor suppression arising as later evolutionary developments. That's because p53-like genes are found in invertebrates, including tiny nematode worms.

"Worms live for two weeks," Dötsch said. "They don't need a tumor suppressor, but they do need to worry about the genetic stability of their germ cells." It turns out the worm version of the gene also resembles p63 more closely than it does p53.

The findings also help to explain what happens in young women who undergo chemotherapy that so often leads them to become infertile as a result, Dötsch noted. It may even be possible to devise strategies to counteract the players responsible for activating TAp63a once it is found or others in the pathway, he said. Unfortunately, that might not be such a good idea.

"If oocytes are damaged, there is probably good reason for them to be destroyed," he said.

###

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011-02-18

Researchers have found an altogether unexpected connection between a hormone produced in bone and male fertility. The study in the February 18th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication, shows that the skeletal hormone known as osteocalcin boosts testosterone production to support the survival of the germ cells that go on to become mature sperm.

The findings in mice provide the first evidence that the skeleton controls reproduction through the production of hormones, according to Gerard Karsenty of Columbia University and his colleagues.

Bone was once thought of as a ...

2011-02-18

This release is available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and Chinese on EurekAlert! Chinese.

Several American black bears, captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after wandering a bit too close to human communities, have given researchers the opportunity to study hibernation in these large mammals like never before. Surprisingly, the new findings show that although black bears only reduce their body temperatures slightly during hibernation, their metabolic activity drops dramatically, slowing to about 25 percent of their normal, active rates.

This ...

2011-02-18

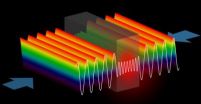

New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light ...

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...

2011-02-18

NEW YORK (February 17, 2011) – Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center have discovered that the skeleton acts as a regulator of fertility in male mice through a hormone released by bone, known as osteocalcin.

The research, led by Gerard Karsenty, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, is slated to appear online on February 17 in Cell, ahead of the journal's print edition, scheduled for March 4.

Until now, interactions between bone and the reproductive system have focused only on the influence ...

2011-02-18

Scientific advice on the consequences of specific policy options confronting government decision makers is key to managing global biodiversity change.

That's the view of leading scientists anxiously anticipating the first meeting of a new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-like mechanism for biodiversity at which its workings and work program will be defined.

Writing in the journal Science, the scientists say the new mechanism, called the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), should adopt a modified working approach ...

2011-02-18

The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds.

Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species.

By examining the sequences of nearly ...

2011-02-18

VIDEO:

Glen Lehman discusses his research.

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON (February 17) –Todd Kuiken, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the Center for Bionic Medicine and Director of Amputee Services at The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), designated the "#1 Rehabilitation Hospital in America" by U.S. News & World Report since 1991, will present the latest in Targeted Muscle Reinnervation (TMR), a bionic limb technology, during the opening press briefing and ...

2011-02-18

INDIANAPOLIS – Unrealistic expectations about genomic medicine have created a "bubble" that needs deflating before it puts the field's long term benefits at risk, four policy experts write in the current issue of the journal Science.

Ten years after the deciphering of the human genetic code was accompanied by over-hyped promises of medical breakthroughs, it may be time to reevaluate funding priorities to better understand how to change behaviors and reap the health benefits that would result.

In addition, the authors say, scientists need to foster more realistic understanding ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Eggs' quality control mechanism explained