(Press-News.org) NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – Rutgers researchers have identified a class of high-strength metal alloys that show potential to make springs, sensors and switches smaller and more responsive.

The alloys could be used in springier blood vessel stents, sensitive microphones, powerful loudspeakers, and components that boost the performance of medical imaging equipment, security systems and clean-burning gasoline and diesel engines.

While these nanostructured metal alloys are not new – they are used in turbine blades and other parts demanding strength under extreme conditions – the Rutgers researchers are pioneers at investigating these new properties.

"We have been doing theoretical studies on these materials, and our computer modeling suggests they will be super-responsive," said Armen Khachaturyan, professor of Materials Science and Engineering in the Rutgers School of Engineering. He and postdoctoral researcher Weifeng Rao believe these materials can be a hundred times more responsive than today's materials in the same applications.

Writing in the March 11 issue of the journal Physical Review Letters, the researchers describe how this class of metals with embedded nanoparticles can be highly elastic, or "springy," and can convert electrical and magnetic energy into movement or vice-versa. Materials that exhibit these properties are known among scientists and engineers as "functional" materials.

One class of functional materials generates an electrical voltage when the material is bent or compressed. Conversely, when the material is exposed to an electric field, it will deform. Known as piezoelectric materials, they are used in ultrasound instruments; audio components such as microphones, speakers and even venerable record players; autofocus motors in some camera lenses; spray nozzles in inkjet printer cartridges; and several types of electronic components.

In another class of functional materials, changes in magnetic fields deform the material and vice-versa. These magnetorestrictive materials have been used in naval sonar systems, pumps, precision optical equipment, medical and industrial ultrasonic devices, and vibration and noise control systems.

The materials that Khachaturyan and Rao are investigating are technically known as "decomposed two-phase nanostructured alloys." They form by cooling metals that were exposed to high temperatures at which the nanosized particles of one crystal structure, or phase, are embedded into another type of phase. The resulting structure makes it possible to deform the metal under an applied stress while allowing the metal to snap back into place when the stress is removed.

These nanostructured alloys might be more effective than traditional metals in applications such blood vessel stents, which have to be flexible but can't lose their "springiness." In the piezoelectric and magnetorestrictive components, the alloy's potential to snap back into shape after deforming – a property known as non-hysteresis – could improve energy efficiency over traditional materials that require energy input to restore their original shapes.

In addition to potentially showing responses far greater than traditional materials, the new materials may be tunable; that is, they may exhibit smaller or larger shape changes and output force based on varying mechanical, electrical or magnetic input and the material processing.

The researchers hope to test the results of their computer simulations on actual metals in the near future.

INFORMATION:

The Rutgers team collaborated with Manfred Wittig, professor of Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Maryland. Their research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Rutgers researchers identify materials that may deliver more 'bounce'

Springy nanostructured metals hold promise of making engines, medical equipment, security systems more efficient and effective

2011-03-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

When leukemia returns, gene that mediates response to key drug often mutated

2011-03-10

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – March 9, 2011) Despite dramatically improved survival rates for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), relapse remains a leading cause of death from the disease. Work led by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital investigators identified mutations in a gene named CREBBP that may help the cancer resist steroid treatment and fuel ALL's return.

CREBBP plays an important role in normal blood cell development, helping to switch other genes on and off. In this study, researchers found that 18.3 percent of the 71 relapsed-ALL patients carried alterations ...

Gene variant influences chronic kidney disease risk

2011-03-10

A team of researchers from the United States and Europe has identified a single genetic mutation in the CUBN gene that is associated with albuminuria both with and without diabetes. Albuminuria is a condition caused by the leaking of the protein albumin into the urine, which is an indication of kidney disease.

The research team, known as the CKDGen Consortium, examined data from several genome-wide association studies to identify missense variant (I2984V) in the CUBN gene. The association between the CUBN variant and albuminuria was observed in 63,153 individuals with ...

New microscope decodes complex eye circuitry

2011-03-10

VIDEO:

Ganglion cells preferentially form synapses with those amacrine cells whose dendrites run in the direction opposite -- seen from the ganglion cell - to the preferred direction of motion (amacrine...

Click here for more information.

The sensory cells in the retina of the mammalian eye convert light stimuli into electrical signals and transmit them via downstream interneurons to the retinal ganglion cells which, in turn, forward them to the brain. The interneurons ...

Physicists measure current-induced torque in nonvolatile magnetic memory devices

2011-03-10

ITHACA, N.Y. - Tomorrow's nonvolatile memory devices – computer memory that can retain stored information even when not powered – will profoundly change electronics, and Cornell University researchers have discovered a new way of measuring and optimizing their performance.

Using a very fast oscilloscope, researchers led by Dan Ralph, the Horace White Professor of Physics, and Robert Buhrman, the J.E. Sweet Professor of Applied and Engineering Physics, have figured out how to quantify the strength of current-induced torques used to write information in memory devices ...

NASA and other satellites keeping busy with this week's severe weather

2011-03-10

Satellites have been busy this week covering severe weather across the U.S. Today, the GOES-13 satellite and NASA's Aqua satellite captured an image of the huge stretch of clouds associated with a huge and soggy cold front as it continues its slow march eastward. Earlier this week, NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite captured images of severe weather that generated tornadoes over Louisiana.

Today the eastern third of the U.S. is being buffered by a large storm that stretches from southeastern Minnesota east to Wisconsin and Michigan, then south through ...

International panel revises 'McDonald Criteria' for diagnosing multiple sclerosis

2011-03-10

International Panel Revises "McDonald Criteria" for Diagnosing MS -- Use of new data should speed diagnosis -- Publication coincides with MS Awareness Week

An international panel has revised and simplified the "McDonald Criteria" commonly used to diagnose multiple sclerosis, incorporating new data that should speed the diagnosis without compromising accuracy. The International Panel on Diagnosis of MS, organized and supported by the National MS Society and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, was chaired by Chris H. Polman, MD, PhD ...

MIT scientists identify new H1N1 mutation that could allow virus to spread more easily

2011-03-10

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- In the fall of 1917, a new strain of influenza swirled around the globe. At first, it resembled a typical flu epidemic: Most deaths occurred among the elderly, while younger people recovered quickly. However, in the summer of 1918, a deadlier version of the same virus began spreading, with disastrous consequence. In total, the pandemic killed at least 50 million people — about 3 percent of the world's population at the time.

That two-wave pattern is typical of pandemic flu viruses, which is why many scientists worry that the 2009 H1N1 ("swine") flu ...

New study proves the brain has 3 layers of working memory

2011-03-10

Researchers from Rice University and Georgia Institute of Technology have found support for the theory that the brain has three concentric layers of working memory where it stores readily available items. Memory researchers have long debated whether there are two or three layers and what the capacity and function of each layer is.

In a paper in the March issue of the Journal of Cognitive Psychology, researchers found that short-term memory is made up of three areas: a core focusing on one active item, a surrounding area holding at least three more active items, and a ...

Giving children the power to be scientists

2011-03-10

Children who are taught how to think and act like scientists develop a clearer understanding of the subject, a study has shown.

The research project led by The University of Nottingham and The Open University has shown that school children who took the lead in investigating science topics of interest to them gained an understanding of good scientific practice.

The study shows that this method of 'personal inquiry' could be used to help children develop the skills needed to weigh up misinformation in the media, understand the impact of science and technology on everyday ...

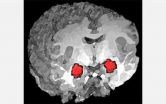

Researchers selectively control anxiety pathways in the brain

2011-03-10

A new study sheds light--both literally and figuratively--on the intricate brain cell connections responsible for anxiety.

Scientists at Stanford University recently used light to activate mouse neurons and precisely identify neural circuits that increase or decrease anxiety-related behaviors. Pinpointing the origin of anxiety brings psychiatric professionals closer to understanding anxiety disorders, the most common class of psychiatric disease.

A research team led by Karl Deisseroth, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and bioengineering, identified ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Addictive digital habits in early adolescence linked to mental health struggles, study finds

As tropical fish move north, UT San Antonio researcher tracks climate threats to Texas waterways

Rich medieval Danes bought graves ‘closer to God’ despite leprosy stigma, archaeologists find

Brexpiprazole as an adjunct therapy for cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia

Applications of endovascular brain–computer interface in patients with Alzheimer's disease

Path Planning Transformers supervised by IRRT*-RRMS for multi-mobile robots

Nurses can deliver hospital care just as well as doctors

From surface to depth: 3D imaging traces vascular amyloid spread in the human brain

Breathing tube insertion before hospital admission for major trauma saves lives

Unseen planet or brown dwarf may have hidden 'rare' fading star

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

International research team solves mystery behind rare clotting after adenoviral vaccines or natural adenovirus infection

The most common causes of maternal death may surprise you

A new roadmap spotlights aging as key to advancing research in Parkinson’s disease

Research alert: Airborne toxins trigger a unique form of chronic sinus disease in veterans

University of Houston professor elected to National Academy of Engineering

UVM develops new framework to transform national flood prediction

Study pairs key air pollutants with home addresses to track progression of lost mobility through disability

Keeping your mind active throughout life associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk

TBI of any severity associated with greater chance of work disability

Seabird poop could have been used to fertilize Peru's Chincha Valley by at least 1250 CE, potentially facilitating the expansion of its pre-Inca society

Resilience profiles during adversity predict psychological outcomes

AI and brain control: A new system identifies animal behavior and instantly shuts down the neurons responsible

Suicide hotline calls increase with rising nighttime temperatures

[Press-News.org] Rutgers researchers identify materials that may deliver more 'bounce'Springy nanostructured metals hold promise of making engines, medical equipment, security systems more efficient and effective