(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – The discovery of a fundamental, previously unknown property of microbial nanowires in the bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens that allows electron transport across long distances could revolutionize nanotechnology and bioelectronics, says a team of physicists and microbiologists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Their findings reported in the Aug. 7 advance online issue of Nature Nanotechnology may one day lead to cheaper, nontoxic nanomaterials for biosensors and solid state electronics that interface with biological systems.

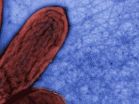

Lead microbiologist Derek Lovley with physicists Mark Tuominen, Nikhil Malvankar and colleagues, say networks of bacterial filaments, known as microbial nanowires because they conduct electrons along their length, can move charges as efficiently as synthetic organic metallic nanostructures, and they do it over remarkable distances, thousands of times the bacterium's length.

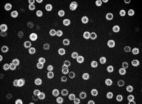

Networks of microbial nanowires coursing through biofilms, which are cohesive aggregates of billions of cells, give this biological material conductivity comparable to that found in synthetic conducting polymers, which are used commonly in the electronics industry.

Lovley says, "The ability of protein filaments to conduct electrons in this way is a paradigm shift in biology and has ramifications for our understanding of natural microbial processes as well as practical implications for environmental clean-up and the development of renewable energy sources."

The discovery represents a fundamental change in understanding of biofilms, Malvankar adds. "In this species, the biofilm contains proteins that behave like a metal, conducting electrons over a very long distance, basically as far as you can extend the biofilm."

Tuominen, the lead physicist, adds, "This discovery not only puts forward an important new principle in biology but in materials science. We can now investigate a range of new conducting nanomaterials that are living, naturally occurring, nontoxic, easier to produce and less costly than man-made. They may even allow us to use electronics in water and moist environments. It opens exciting opportunities for biological and energy applications that were not possible before."

The researchers report that this is the first time metallic-like conduction of electrical charge along a protein filament has been observed. It was previously thought that such conduction would require a mechanism involving a series of other proteins known as cytochromes, with electrons making short hops from cytochrome to cytochrome. By contrast, the UMass Amherst team has demonstrated long-range conduction in the absence of cytochromes. The Geobacter filaments function like a true wire.

In nature, Geobacter use their microbial nanowires to transfer electrons onto iron oxides, natural rust-like minerals in soil, that for Geobacter serve the same function as oxygen does for humans. "What Geobacter can do with its nanowires is akin to breathing through a snorkel that's 10 kilometers long," says Malvankar.

The UMass Amherst group had proposed in a 2005 paper in Nature that Geobacter's nanowires might represent a fundamental new property in biology, but they didn't have a mechanism, so were met with considerable skepticism. To continue experimenting, Lovley and colleagues took advantage of the fact that in the laboratory Geobacter will grow on electrodes, which replace the iron oxides. On electrodes, the bacteria produce thick, electrically conductive biofilms. In a series of studies with genetically modified strains, the researchers found the metallic-like conductivity in the biofilm could be attributed to a network of nanowires spreading throughout the biofilm.

These special structures are tunable in a way not seen before, the UMass Amherst researchers found. Tuominen points out that it's well known in the nanotechnology community that artificial nanowire properties can be changed by altering their surroundings. Geobacter's natural approach is unique in allowing scientists to manipulate conducting properties by simply changing the temperature or regulating gene expression to create a new strain, for example. Malvankar adds that by introducing a third electrode, a biofilm can act like a biological transistor, able to be switched on or off by applying a voltage.

Another advantage Geobacter offers is its ability to produce natural materials that are more eco-friendly and quite a bit less expensive than man-made. Quite a few of today's nanotech materials are expensive to produce, many requiring rare elements, says Tuominen. Geobacter is a true natural alternative. "As someone who studies materials, I see the nanowires in this biofilm as a new material, one that just happens to be made by nature. It's exciting that it might bridge the gap between solid state electronics and biological systems. It is biocompatible in a way we haven't seen before."

Lovley quips, "We're basically making electronics out of vinegar. It can't get much cheaper or more 'green' than that."

Finally, this is a story about cross-disciplinary collaboration, which is much harder to accomplish than it sounds, Lovley says. "We were very lucky to have flexible funding from the Office of Naval Research, the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation that allowed us to follow some hunches. Also, it took a physics doctoral student brave enough to come over to microbiology to work with something wet and slimy." That student, Nikhil Malvankar, now is a postdoctoral researcher who with Lovley and Tuominen will continue exploring what gives Geobacter's protein filaments their unique electrical properties.

INFORMATION:

Contact: Janet Lathrop, 413/545-0444; jlathrop@admin.umass.edu

Derek Lovley, 413/695-1690; dlovley@microbio.umass.edu

Mark Tuominen, 413/545-1944; tuominen@physics.umass.edu

Nikhil Malvankar, 413/313-3179; nikhil@physics.umass.edu

Photos are available at: www.geobacter.org and at: www.umass.edu/newsoffice/

UMass Amherst research team discovers new conducting properties of bacteria-produced wires

2011-08-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

ESDS Announces the Launch of eNlight - The Dynamic Cloud Computing Platform

2011-08-09

eNlight - Taking the Cloud Computing Industry by Storm

ESDS is pleased to announce the launch of its eNlight Cloud Computing Platform - the World's first intelligent cloud that truly does justice to the concept of Cloud Computing. eNlight Cloud is an addition to the company's existing portfolio of other software products and managed hosting services and was designed with small to medium sized companies in mind. In the existing Cloud Hosting market most companies offer the option to pay for fixed use. Companies try to market it as flexible hosting by claiming you can ...

HIA-LI Recognizes Finalists for Prestigious 17th Annual Business Achievement Awards

2011-08-09

HIA-LI, the recognized voice for business on Long Island, is pleased to announce the finalists for the prestigious HIA-LI 17th Annual Business Achievement Awards competition. Winners will be announced during a gala luncheon event held at the Crest Hollow Country Club in Woodbury, NY, 11:30 AM - 2:00 PM, Tuesday, September 13, 2011. More information about the awards event is available at: http://bit.ly/hia-li-baa-event-2011.

"HIA-LI is pleased to recognize these finalists who are among the best run and highest performing companies on Long Island for our HIA-LI Business ...

The nanoscale secret to stronger alloys

2011-08-09

Long before they knew they were doing it – as long ago as the Wright Brother's first airplane engine – metallurgists were incorporating nanoparticles in aluminum to make a strong, hard, heat-resistant alloy. The process is called solid-state precipitation, in which, after the melt has been quickly cooled, atoms of alloying metals migrate through a solid matrix and gather themselves in dispersed particles measured in billionths of a meter, only a few-score atoms wide.

Key to the strength of these precipitation-hardened alloys is the size, shape, and uniformity of the ...

New resource to unlock the role of microRNAs

2011-08-09

A new resource to define the roles of microRNAs is announced today in Nature Biotechnology. The resource, called mirKO, gives researchers access to tools to investigate the biological role and significance for human health of these enigmatic genes.

mirKO is a "library" of mutant mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells in which individual, or clustered groups of microRNA genes, have been deleted. Using these tools researchers can create cells or mice lacking specific microRNAs, study expression using fluorescent markers, or inactivate the gene in specific tissues or at specific ...

UNC-Duke ties lead to collaborative finding about cell division & metabolism

2011-08-09

Chapel Hill, NC – Cells are the building blocks of the human body. They are a focus of scientific study, because when things go wrong at the cellular and molecular level the consequences for human health are often significant.

A new finding based on multiple collaborations between UNC and Duke scientists over several years points to new avenues for investigation of cell metabolism that may provide insights into diseases ranging from neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease to certain types of cancers.

The finding, published today in the ...

Brain's map of space falls flat when it comes to altitude

2011-08-09

Animal's brains are only roughly aware of how high-up they are in space, meaning that in terms of altitude the brain's 'map' of space is surprisingly flat, according to new research.

In a study published online today in Nature Neuroscience, scientists studied cells in or near a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which forms the brain's map of space, to see whether they were activated when rats climbed upwards.

The study, supported by the Wellcome Trust, looked at two types of cells known to be involved in the brain's representation of space: grid cells, which ...

Cell-based alternative to animal testing

2011-08-09

European legislation restricts animal testing within the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries and companies are increasingly looking at alternative systems to ensure that their products are safe to use. Research published in BioMed Central's open access journal BMC Genomics demonstrates that the response of laboratory grown human cells can now be used to classify chemicals as sensitizing, or non-sensitizing, and can even predict the strength of allergic response, so providing an alternative to animal testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis can result in itching and eczema ...

Research discovers frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in TCC of the bladder

2011-08-09

August 8th, 2011, Shenzhen, China – BGI, the world's largest genomics organization, Peking University Shenzhen Hospital and Shenzhen Second People's Hospital, announced today that the study on frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder was published online in Nature Genetics. This study provides a valuable genetic basis for future studies on TCC, suggesting that aberration of chromatin regulation might be one of the features of bladder cancer.

Bladder cancer is the ninth most common type of cancer worldwide, which ...

How yeast chromosomes avoid the bad breaks

2011-08-09

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (August 7, 2011) – The human genome is peppered with repeated DNA elements that can vary from a few to thousands of consecutive copies of the same sequence. During meiosis—the cell division that produces sperm and eggs—repetitive elements place the genome at risk for dangerous rearrangements from genome reshuffling. This recombination typically does not occur in repetitive DNA, in part because much of it is assembled into specialized heterochromatin. Other mechanisms that restrain recombination in repetitive DNA have remained elusive, until now.

In a ...

Researchers gain new insights into how tumor cells are fed

2011-08-09

Philadelphia, PA, August 8, 2011 – Researchers have gained a new understanding of the way in which growing tumors are fed and how this growth can be slowed via angiogenesis inhibitors that eliminate the blood supply to tumors. This represents a step forward towards developing new anti-cancer drug therapies. The results of this study have been published today in the September issue of The American Journal of Pathology.

"The central role of capillary sprouting in tumor vascularization makes it an attractive target for anticancer therapy. Our observations suggest, however, ...