(Press-News.org) For years, researchers seeking new therapies for traumatic brain injury have been tantalized by the results of animal experiments with stem cells. In numerous studies, stem cell implantation has substantially improved brain function in experimental animals with brain trauma. But just how these improvements occur has remained a mystery.

Now, an important part of this puzzle has been pieced together by researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. In experiments with both laboratory rats and an apparatus that enabled them to simulate the impact of trauma on human neurons, they identified key molecular mechanisms by which implanted human neural stem cells — stem cells that are in the process of developing into neurons but have not yet taken their final form — aid recovery from traumatic axonal injury.

A significant component of traumatic brain injury, traumatic axonal injury involves damage to axons and dendrites, the filaments that extend out from the bodies of the neurons. The damage continues after the initial trauma, since the axons and dendrites respond to injury by withdrawing back to the bodies of the neurons.

"Axons and dendrites are the basis of neuron-to-neuron communication, and when they are lost, neuron function is lost," said UTMB professor Ping Wu, lead author of a paper on the research appearing in the Journal of Neurotrauma. "In this study, we found that our stem cell transplantation both prevents further axonal injury and promotes axonal regrowth, through a number of previously unknown molecular mechanisms."

The UTMB researchers began their investigation with a clue from their previous work: they had determined that their neural stem cells secreted a substance called glial derived neurotrophic factor, which seemed to help injured rat brains recover from injury. As a first step toward identifying the processes by which GDNF and neural stem cell transplantation produced their beneficial effects, Wu enlisted UTMB professors Larry Denner, Douglas Dewitt and Dr. Donald Prough to use proteomic techniques to compare injured rat brains with injured rat brains into which neural stem cells had been transplanted.

"We identified about 400 proteins that respond differently after injury and after grafting with neural stem cells," Wu said. "When we grouped them using a state-of-the-art Internet database, we found that a group of cytoskeleton proteins was being changed, and in particular one called alpha-smooth muscle actin, which had never been reported in the neurons before."

Because so many of the proteins that changed were related to axonal structure and function, the UTMB scientists then focused on traumatic axonal injury. Initially working with rats, they confirmed that axons and dendrites suffered damage from trauma; implanted neural stem cells reduced this harm, as well as lowering levels of alpha-smooth muscle actin inside neurons that were raised after trauma.

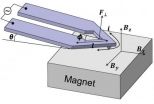

To probe further into the molecular details of GDNF's role in reducing traumatic axonal injury, the researchers used a system in which human neurons were placed on a flexible membrane that was then suddenly distended with a precisely calibrated puff of gas. Their goal was to simulate the sudden compression and stretching forces exerted on brain cells by a blow to the head.

Initial results from this "rapid stretch injury model" matched those seen in rat experiments, with GDNF protecting axons and dendrites from additional damage in the period after trauma and significantly reducing alpha-smooth muscle actin levels boosted by the simulated injury. In addition, they found evidence linking alpha-smooth muscle actin with RhoA, a small protein that blocks axonal growth after injury. Finally, again taking a cue from their proteomic study, they turned their attention to one component of a protein known as calcineurin, finding that it interacted with GDNF to protect axons and dendrites in the RSI model.

"We're quite excited about these discoveries, because they're highly novel — we now know much more about how GDNF protects axons and dendrites from further injury and promotes their re-growth after trauma," Wu said. "This kind of detailed study is essential to developing safe and effective therapies for traumatic brain injury."

INFORMATION: Other authors of the Journal of Neurotrauma paper include graduate students Enyin Wang, Junling Gao and Tiffany Dunn; assistant research lab director Margaret Parsley; Qin Yang of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, Lin Zhang of Sichuan University in Chengdu, China; and professors Douglas DeWitt, Larry Denner and Donald Prough. Support for this research was provided by the U.S. Army, the Coalition for Brain Injury Research, the Moody Center for Traumatic Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Research, Mission Connect, the TIRR Foundation, the China Scholarship Council, the John S. Dunn Research Foundation and the Cullen Foundation.

END

Researchers at the University of Oviedo (Spain) have come up with a way of tagging gunpowder which allows its illegal use to be detected even after it has been detonated. Based on the addition of isotopes, the technique can also be used to track and differentiate between wild fish and those from a fish farm, such as trout and salmon.

A new method for tagging and identifying objects, substances and living beings has just been presented in this month's issue of the Analytical Chemistry journal. Its creators are scientists at the University of Oviedo who have patented the ...

A new study on African bats provides a vital clue for unravelling the mysteries in Australia's battle with the deadly Hendra virus.

The study focused on an isolated colony of straw-coloured fruit bats on islands off the west coast of central Africa. By capturing the bats and collecting blood samples, scientists discovered these animals have antibodies that can neutralise deadly viruses known in Australia and Asia.

The paper is published today, 12 January, in the journal PLoS ONE, and is a collaboration of the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of ...

Polymer nano-films and nano-composites are used in a wide variety of applications from food packaging to sports equipment to automotive and aerospace applications. Thermal analysis is routinely used to analyze materials for these applications, but the growing trend to use nanostructured materials has made bulk techniques insufficient.

In recent years an atomic force microscope-based technique called nanoscale thermal analysis (nanoTA) has been employed to reveal the temperature-dependent properties of materials at the sub-100 nm scale. Typically, nanothermal analysis ...

BOSTON, January 12, 2012: A research collaboration between the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and Children's Hospital Boston has developed "smart" injectable nanotherapeutics that can be programmed to selectively deliver drugs to the cells of the pancreas. Although this nanotechnology will need significant additional testing and development before being ready for clinical use, it could potentially improve treatment for Type I diabetes by increasing therapeutic efficacy and reducing side effects.

The approach was found to increase ...

SANTA CRUZ, CA--Robotics experts at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the University of Washington (UW) have completed a set of seven advanced robotic surgery systems for use by major medical research laboratories throughout the United States. After a round of final tests, five of the systems will be shipped to medical robotics researchers at Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, University of Nebraska, UC Berkeley, and UCLA, while the other two systems will remain at UC Santa Cruz and UW.

"We decided to follow an open-source model, because if all ...

University of Illinois researchers have shown that by tuning the properties of laser light illuminating arrays of metal nanoantennas, these nano-scale structures allow for dexterous optical tweezing as well as size-sorting of particles.

"Nanoantennas are extremely popular right now because they are really good at concentrating optical fields in small areas," explained Kimani Toussaint, Jr., an assistant professor of mechanical science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "In this work, we demonstrate for the first time the use of arrays ...

Racial discrimination may be harmful to your health, according to new research from Rice University sociologists Jenifer Bratter and Bridget Gorman.

In the study, "Is Discrimination an Equal Opportunity Risk? Racial Experiences, Socio-economic Status and Health Status Among Black and White Adults," the authors examined data containing measures of social class, race and perceived discriminatory behavior and found that approximately 18 percent of blacks and 4 percent of whites reported higher levels of emotional upset and/or physical symptoms due to race-based treatment. ...

The perception that women are scarce leads men to become impulsive, save less, and increase borrowing, according to new research from the University of Minnesota's Carlson School of Management.

"What we see in other animals is that when females are scarce, males become more competitive. They compete more for access to mates," says Vladas Griskevicius, an assistant professor of marketing at the Carlson School and lead author of the study. "How do humans compete for access to mates? What you find across cultures is that men often do it through money, through status and ...

Why do we like fatty foods so much? We can blame our taste buds.

Our tongues apparently recognize and have an affinity for fat, according to researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. They have found that variations in a gene can make people more or less sensitive to the taste of fat.

The study is the first to identify a human receptor that can taste fat and suggests that some people may be more sensitive to the presence of fat in foods. The study is available online in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Investigators found that people with ...

SEATTLE – Continuing a series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 about the genetic causes of the third most common form of inherited muscular dystrophy, an international team of researchers led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified the genes and proteins that damage muscle cells, as well as the mechanisms that can cause the disease. The findings are online and will be reported in the Jan. 17 print edition of the journal Developmental Cell.

The discovery could lead to a biomarker-based test for diagnosing facioscapulohumeral muscular ...