Nonstick coating of a protein found in semen reduces HIV infection

2010-09-24

(Press-News.org) A non-stick coating for a substance found in semen dramatically lowers the rate of infection of immune cells by HIV a new study has found.

The new material is a potential ingredient for microbicides designed to reduce transmission of HIV, a team from the University of Rochester Medical Center and the University of California, San Diego reports in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

The coating clings to fibrous strings and mats of protein called SEVI–for semen-derived enhancer of viral infection–which was first discovered just three years ago. SEVI seems to attract the virus and deposit it onto the surface of T-cells, components of the immune system that are the primary target of HIV infection, and may play an important role in sexual transmission of HIV.

Like the fibrous strings that bind senile plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease, SEVI is a kind of protein superstructure called an amyloid.

Jerry Yang, associate professor of chemistry at UC San Diego and his research group developed non-stick coatings for amyloids as a potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease in 2006. Their idea was to minimize damage by preventing amyloid proteins from interacting with other molecules in the brain.

When this new amyloid, SEVI, was discovered in 2007, Yang was interested in testing whether the coating strategy might interfere with SEVI's role in promoting HIV infection.

Yang's group teamed up with a researchers led by Stephen Dewhurst, chair of the microbiology and immunology department at the University of Rochester Medical Center, who studies HIV.

"We tested one of our molecules out on SEVI and found it was able to stop SEVI-enhanced infection of HIV in cells," Yang said. "It works in semen too. Something in semen enhances viral infection – SEVI and maybe other things. This molecule stops that."

When the researchers added the molecule that forms non-stick coatings to a mix of SEVI, virus and cells, rates of infection dropped to levels observed when SEVI was absent. They saw a similar effect with semen as well, evidence that this potential microbicide supplement works to inhibit infection within a mixture of proteins and other molecules found in seminal fluid.

The coating molecule is a modified form of thioflavin-T, a dye that stains amyloid proteins. It fits in between the individual small proteins that cluster to form SEVI and blocks SEVI's interactions with both the virus and the target immune cells.

"Other people have tried to do the same thing by targeting the virus or the cells it infects. What we do is target the mediator between the virus and the cells," Yang said. "By neutralizing SEVI, we prevent at least one way for HIV to attach to the cells."

The new molecule has another advantage. Unlike many current microbicide candidates aimed at reducing HIV infection, this one doesn't cause inflammation in cervical cells.

"Recent studies have shown for the first time that a topical microbicide gel can protect women from HIV-1 infection. This is a huge step forward but not a perfect solution. We need to figure out ways to further improve protection - and our studies suggest one way of doing so," said Dewhurst, who is the corresponding author of the report. "It may be possible to produce a next-generation microbicide that includes both an antiviral agent, as has been used in the past, and an agent that targets SEVI. We're very excited about exploring this idea."

INFORMATION:

The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation funded this work.

Additional co-authors include Joanna Olsen, Caitlin Brown, Todd Doran, Rajesh Srivastava, Changyong Feng and Bradley Nilsson of the University of Rochester, and Christina Capule and Mark Rubinshtein of the University of California, San Diego.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2010-09-24

Like a well-crafted football play designed to block the opposing team's offensive drive to the end zone, the body constantly executes complex 'plays' or sequences of events to initiate, or block, different actions or functions.

Scientists at the University of Rochester Medical Center recently discovered a potential molecular playbook for blocking cardiac hypertrophy, the unwanted enlargement of the heart and a well-known precursor of heart failure. Researchers uncovered a specific molecular chain of events that leads to the inhibition of this widespread risk factor. ...

2010-09-24

Troy, N.Y. – Individuals within a networked system coordinate their activities by communicating to each other information such as their position, speed, or intention. At first glance, it seems that more of this communication will increase the harmony and efficiency of the network. However, scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that this is only true if the communication and its subsequent action are immediate.

Using statistical physics and network science, the researchers were able to find something very fundamental about synchronization and coordination: ...

2010-09-24

In research led by a Saint Louis University surgeon, investigators found that women who give birth after suffering pelvic fractures receive C-sections at more than double normal rates despite the fact that vaginal delivery after such injuries is possible. In addition, women reported lingering, yet often treatable, symptoms following their pelvic fracture injuries, from urinary complications to post-traumatic stress disorder.

The study, published in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, retrospectively reviewed the cases of 71 women who had suffered pelvic fractures, ...

2010-09-24

PASADENA, Calif.—Computers, light bulbs, and even people generate heat—energy that ends up being wasted. With a thermoelectric device, which converts heat to electricity and vice versa, you can harness that otherwise wasted energy. Thermoelectric devices are touted for use in new and efficient refrigerators, and other cooling or heating machines. But present-day designs are not efficient enough for widespread commercial use or are made from rare materials that are expensive and harmful to the environment.

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) ...

2010-09-24

RENO, Nev. – Like the little engine that could, the University of Nevada, Reno experiment to transform wastewater sludge to electrical power is chugging along, dwarfed by the million-gallon tanks, pipes and pumps at the Truckee Meadows Water Reclamation Facility where, ultimately, the plant's electrical power could be supplied on-site by the process University researchers are developing.

"We are very pleased with the results of the demonstration testing of our research," Chuck Coronella, principle investigator for the research project and an associate professor of chemical ...

2010-09-24

WASHINGTON– In recent decades, the rate at which humans worldwide are pumping dry the vast underground stores of water that billions depend on has more than doubled, say scientists who have conducted an unusual, global assessment of groundwater use.

These fast-shrinking subterranean reservoirs are essential to daily life and agriculture in many regions, while also sustaining streams, wetlands, and ecosystems and resisting land subsidence and salt water intrusion into fresh water supplies. Today, people are drawing so much water from below that they are adding enough ...

2010-09-24

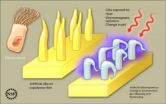

University of Southern Mississippi scientists recently imitated Mother Nature by developing, for the first time, a new, skinny-molecule-based material that resembles cilia, the tiny, hair-like structures through which organisms derive smell, vision, hearing and fluid flow.

While the new material isn't exactly like cilia, it responds to thermal, chemical, and electromagnetic stimulation, allowing researchers to control it and opening unlimited possibilities for future use.

This finding is published in today's edition of the journal Advanced Functional Materials. The ...

2010-09-24

Archaeologists who interpret Stone Age culture from discoveries of ancient tools and artifacts may need to reanalyze some of their conclusions.

That's the finding suggested by a new study that for the first time looked at the impact of water buffalo and goats trampling artifacts into mud.

In seeking to understand how much artifacts can be disturbed, the new study documented how animal trampling in a water-saturated area can result in an alarming amount of disturbance, says archaeologist Metin I. Eren, a graduate student at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, and ...

2010-09-24

University of California, Berkeley, and Yale University scientists have recreated the tremendous pressures and high temperatures deep in the Earth to resolve a long-standing puzzle: why some seismic waves travel faster than others through the boundary between the solid mantle and fluid outer core.

Below the earth's crust stretches an approximately 1,800-mile-thick mantle composed mostly of a mineral called magnesium silicate perovskite (MgSiO3). Below this depth, the pressures are so high that perovskite is compressed into a phase known as post-perovskite, which comprises ...

2010-09-24

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report this month that MALAT1, a long non-coding RNA that is implicated in certain cancers, regulates pre-mRNA splicing – a critical step in the earliest stage of protein production. Their study appears in the journal Molecular Cell.

Nearly 5 percent of the human genome codes for proteins, and scientists are only beginning to understand the role of the rest of the "non-coding" genome. Among the least studied non-coding genes – which are transcribed from DNA to RNA but generally are not translated into proteins – are the long non-coding RNAs ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Nonstick coating of a protein found in semen reduces HIV infection