(Press-News.org) Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y -- The next time you set a trap for that rat running around in your basement, here's something to consider: you are going up against an opponent whose ability to assess the situation and make decisions is statistically just as good as yours.

A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) study that compared the ability of humans and rodents to make perceptual decisions based on combining different modes of sensory stimuli—visual and auditory cues, for instance—has found that just like humans, rodents also combine multisensory information and exploit it in a "statistically optimal" way -- or the most efficient and unbiased way possible.

"Statistically optimal combination of multiple sensory stimuli has been well documented in humans, but many have been skeptical about this behavior occurring in other species," explains Assistant Professor Anne Churchland, Ph.D., a neuroscientist who led the new study. "Our work is the first demonstration of its occurrence in rodents." The study appears in the March 14 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

This discovery is exciting, according to Churchland, because it suggests that the same evolutionarily conserved neural circuits underlie this behavior in both humans and rodents. "By observing this behavior in rodents, we have a chance to explore its neural basis – something that is not feasible to do in people," Churchland says.

Such investigations, she hopes, will explain why patients with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) integrate sensory information in an atypical and less-than-optimal way, relative to healthy people. "We can use our rat model to 'look under the hood' to understand how the brain is combining multisensory information and be in a better position to develop treatments for these disorders in people."

Churchland and her team tested multisensory integration in humans and rats by designing a task that gauged how the subjects made decisions when presented with visual and auditory stimuli -- separately and in tandem. "We threw in a couple of additional features that made the task challenging enough to simulate a real-life situation," Churchland adds.

Her team also designed the task keeping in mind the caveat that our brains process visual information much slower than auditory information. "Our task included stimuli that were much more dynamic and temporal (time-varying) compared to other studies that have tested multisensory integration, which we regard an important advance in the field," explains Churchland.

Her team now reports that both humans and rats made more accurate decisions when presented with combined multisensory information and that this decision-making was close to being statistically optimal – a mathematical prediction of how well each subject could possibly perform in the task.

The researchers have also found evidence that offers fresh insight into how the brain deals with the challenge of having a visual processing system that's slower that the auditory processing system. "Even though visual and auditory stimuli don't come in exactly at the same time, we think that the brain keeps events in sequence by processing each sensory cue in parallel, fusing the two signals at a later stage and then making a judgment about the fused signal," elaborates Churchland.

Her team next plans to investigate how the two streams of information are being combined and how the brain combines sensory experience with memory. "Now that we have a good animal model in which to investigate these questions, the world—or the brain—is our oyster," she says.

INFORMATION:This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of Health and the John Merck Fund.

"Multisensory decision-making in rats and humans," appears in the Journal of Neuroscience on March 14. The full citation is: David Raposo, John P. Sheppard, Paul R. Schrater, and Anne K. Churchland.

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. CSHL is ranked number one in the world by Thomson Reuters for impact of its research in molecular biology and genetics. The Laboratory has been home to eight Nobel Prize winners. Today, CSHL's multidisciplinary scientific community is more than 350 scientists strong and its Meetings & Courses program hosts more than 11,000 scientists from around the world each year. Tens of thousands more benefit from the research, reviews, and ideas published in journals and books distributed internationally by CSHL Press. The Laboratory's education arm also includes a graduate school and programs for undergraduates as well as middle and high school students and teachers. CSHL is a private, not-for-profit institution on the north shore of Long Island. For more information, visit www.cshl.edu.

END

(Boston) – Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have found that a health care provider's attitude toward male human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination may influence the implementation of new guidelines. They believe targeted provider education on the benefits of HPV vaccination for male patients, specifically the association of HPV with certain cancers in men, may be important for achieving vaccination goals. These findings appear on-line in the American Journal of Men's Health.

HPV infects approximately 20 million men and women in the United States ...

Children with disruptive behavioural problems and their parents can benefit from peer led parenting classes, claims a study published today on bmj.com.

The authors, from the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, studied parents and children (aged 2-11 years) from 116 families. The parents were seeking help with managing their children's behavioural problems. The study took place between January and December 2010 in Southwark, London, one of the most deprived boroughs in England where there is a high proportion of ethnic minority residents and a high rate of ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich.—A University of Michigan cell biologist and his colleagues have identified a potential drug that speeds up trash removal from the cell's recycling center, the lysosome.

The finding suggests a new way to treat rare inherited metabolic disorders such as Niemann-Pick disease and mucolipidosis Type IV, as well as more common neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, said Haoxing Xu, who led a U-M team that reported its findings March 13 in the online, multidisciplinary journal Nature Communications.

"The implications are far-reaching," ...

What is it that turns an ordinary student into an Erasmus student? A team of researchers at the University Teacher Training College in Vitoria-Gasteiz (UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country) has studied the psychological profile of those students who plan to participate in mobility programmes with that of the ones who are not considering doing so, and has detected signs that would point to differences between the two groups. So it is in fact a subject that invites research. Thanks to this preliminary work, an article has been published in the journal Procedia – Social ...

Studio Boudoir Photography, San Antonio's premier boudoir photography studio, is proud to announce the launch of Boudoir4theCure. The goal of Boudoir4theCure is to raise funds through various events, which will directly benefit the efforts of the Susan G. Komen Foundation to find a cure for breast cancer.

Boudoir has become one of the hottest trends in photography, as more women boldly step in front of the camera to capture an intimate and elegant side of themselves for a significant other. Most women shoot in lingerie, however, a jersey from a favorite sports team, ...

New research at the University of Warwick into 50 years of motherhood manuals has revealed how despite their differences they have always issued advice as orders and set unattainably high standards for new mums and babies.

Angela Davis, from the Department of History at the University of Warwick, carried out 160 interviews with women of all ages and from all backgrounds to explore their experiences of motherhood for her new book, Modern Motherhood: Women and Family in England, 1945-2000.

She spoke to women about the advice given by six childcare 'experts' who had all ...

Research from the University of Warwick suggests suicide rates are much higher in protestant areas than catholic areas.

Professor Sascha Becker from the University of Warwick's Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Society (CAGE) has published his latest paper Knocking on Heaven's Door? Protestantism and Suicide.

The study investigates whether religion is an influence in the decision to commit suicide, above and beyond other matters that may play a role, such as the weather, literacy, mental health or financial situation.

Professor Becker and his co-author, ...

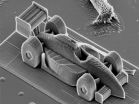

Printing three dimensional objects with incredibly fine details is now possible using "two-photon lithography". With this technology, tiny structures on a nanometer scale can be fabricated. Researchers at the Vienna University of Technology (TU Vienna) have now made a major breakthrough in speeding up this printing technique: The high-precision-3D-printer at TU Vienna is orders of magnitude faster than similar devices (see video). This opens up completely new areas of application, such as in medicine.

Setting a New World Record

The 3D printer uses a liquid resin, which ...

One of the trickiest parts of treating brain conditions is the blood brain barrier, a blockade of cells that prevent both harmful toxins and helpful pharmaceuticals from getting to the body's control center. But, a technique published in JoVE, uses an MRI machine to guide the use of microbubbles and focused ultrasound to help drugs enter the brain, which may open new treatment avenues for devastating conditions like Alzheimer's and brain cancers.

"It's getting close to the point where this could be done safely in humans," said paper-author Meaghan O'Reilly, "there is ...

People often wonder if computers make children smarter. Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, are asking the reverse question: Can children make computers smarter? And the answer appears to be 'yes.'

UC Berkeley researchers are tapping the cognitive smarts of babies, toddlers and preschoolers to program computers to think more like humans.

If replicated in machines, the computational models based on baby brainpower could give a major boost to artificial intelligence, which historically has had difficulty handling nuances and uncertainty, researchers ...