(Press-News.org) Boston, MA —Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) researchers have found that detailed knowledge about your genetic makeup—the interplay between genetic variants and other genetic variants, or between genetic variants and environmental risk factors—may only change your estimated disease prediction risk for three common diseases by a few percentage points, which is typically not enough to make a difference in prevention or treatment plans. It is the first study to revisit claims in previous research that including such information in risk models would eventually help doctors either prevent or treat diseases.

"While identifying a synergistic effect between even a single genetic variant and another risk factor is known to be extremely challenging and requires studies with a very large number of individuals, the benefit of such discovery for risk prediction purpose might be very limited," said lead author Hugues Aschard, research fellow in the Department of Epidemiology.

The study appears online May 24, 2012 and will appear in the June 8, 2012 print issue of The American Journal of Human Genetics.

Scientists have long hoped that using genetic information gleaned from the Human Genome Project and other genetic research could improve disease risk prediction enough to help aid in prevention and treatment. Others have been skeptical that such "personalized medicine" will be of clinical benefit. Still others have argued that there will be benefits in the future, but that current risk prediction algorithms underperform because they don't allow for potential synergistic effects—the interplay of multiple genetic risk markers and environmental factors—instead focusing only on individual genetic markers.

Aschard and his co-authors, including senior author Peter Kraft, HSPH associate professor of epidemiology, examined whether disease risk prediction would improve for breast cancer, type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis if they included the effect of synergy in their statistical models. But they found no significant effect by doing so. "Statistical models of synergy among genetic markers are not 'game changers' in terms of risk prediction in the general population," said Aschard.

The researchers conducted a simulation study by generating a broad range of possible statistical interactions among common environmental exposures and common genetic risk markers related to each of the three diseases. Then they estimated whether such interactions would significantly boost disease prediction risk when compared with models that didn't include these interactions since, to date, using individual genetic markers in such predictions has provided only modest improvements.

For breast cancer, the researchers considered 15 common genetic variations associated with disease risk and environmental factors such as age of first menstruation, age at first birth, and number of close relatives who developed breast cancer. For type 2 diabetes, they looked at 31 genetic variations along with factors such as obesity, smoking status, physical activity, and family history of the disease. For rheumatoid arthritis, they also included 31 genetic variations, as well as two environmental factors: smoking and breastfeeding.

But, for each of these disease models, researchers calculated that the increase in risk prediction sensitivity—when considering the potential interplay between various genetic and environmental factors—would only be between 1% and 3% at best.

"Overall, our findings suggest that the potential complexity of genetic and environmental factors related to disease will have to be understood on a much larger scale than initially expected to be useful for risk prediction. The road to efficient genetic risk prediction, if it exists, is likely to be long," said Aschard.

"For most people, your doctor's advice before seeing your genetic test for a particular disease will be exactly the same as after seeing your tests," added Kraft.

Still, Aschard and his co-authors recommend further study of gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions because it can provide important clues, if not about disease risk, at least about disease causes—which could in turn lead to improved treatment and prevention strategies.

Marilyn Cornelis, research associate in the Department of Nutrition at HSPH, was also a co-author on the study.

###

Support for the study was from the National Institutes of Health (R21 DK084529, 2P01CA87969-11, AR049880, P60 AR047782) through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and from the Fondation Bettencourt–Schueller.

"Inclusion of Gene-Gene and Gene-Environment Interactions Unlikely to Dramatically Improve Risk Prediction for Complex Diseases," Hugues Aschard, Jinbo Chen, Marilyn C. Cornelis, Lori B. Chibnik, Elizabeth W. Karlson, Peter Kraft, The American Journal of Human Genetics, online May 24, 2012

Visit the HSPH website for the latest news, press releases and multimedia offerings.

Harvard School of Public Health is dedicated to advancing the public's health through learning, discovery, and communication. More than 400 faculty members are engaged in teaching and training the 1,000-plus student body in a broad spectrum of disciplines crucial to the health and well being of individuals and populations around the world. Programs and projects range from the molecular biology of AIDS vaccines to the epidemiology of cancer; from risk analysis to violence prevention; from maternal and children's health to quality of care measurement; from health care management to international health and human rights. For more information on the school visit: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu

HSPH on Twitter: http://twitter.com/HarvardHSPH

HSPH on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/harvardpublichealth

HSPH on You Tube: http://www.youtube.com/user/HarvardPublicHealth

HSPH home page: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu

END

(SALT LAKE CITY)—Research into how carbohydrates are converted into energy has led to a surprising discovery with implications for the treatment of a perplexing and potentially fatal neuromuscular disorder and possibly even cancer and heart disease.

Until this study, the cause of this neuromuscular disorder was unknown. But after obtaining DNA from three families with members who have the disorder, a team led by University of Utah scientists Jared Rutter, Ph.D., associate professor of biochemistry and Carl Thummel, Ph.D., professor of human genetics, sequenced two genes ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. — There's nothing like a new pair of eyeglasses to bring fine details into sharp relief. For scientists who study the large molecules of life from proteins to DNA, the equivalent of new lenses have come in the form of an advanced method for analyzing data from X-ray crystallography experiments.

The findings, just published in the journal Science, could lead to new understanding of the molecules that drive processes in biology, medical diagnostics, nanotechnology and other fields.

Like dentists who use X-rays to find tooth decay, scientists use X-rays ...

Research from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that the human olfactory bulb – a structure in the brain that processes sensory input from the nose – differs from that of other mammals in that no new neurons are formed in this area after birth. The discovery, which is published in the scientific journal Neuron, is based on the age-determination of the cells using the carbon-14 method, and might explain why the human sense of smell is normally much worse than that of other animals.

"I've never been so astonished by a scientific discovery," says lead investigator Jonas ...

A new type of male contraceptive could be created thanks to the discovery of a key gene essential for sperm development.

The finding could lead to alternatives to conventional male contraceptives that rely on disrupting the production of hormones, such as testosterone and can cause side-effects such as irritability, mood swings and acne.

Research, led by the University of Edinburgh, has shown how a gene – Katnal1 – is critical to enable sperm to mature in the testes.

If scientists can regulate the Katnal1 gene in the testes, they could prevent sperm from maturing ...

A research team led by the University of Melbourne and Monash University, Australia, has discovered why people can develop life-threatening allergies after receiving treatment for conditions such as epilepsy and AIDS.

The finding could lead to the development of a diagnostic test to determine drug hypersensitivity.

The study published today in the journal Nature, revealed how some drugs inadvertently target the immune system to alter how the body's immune system perceives it's own tissues, making them look foreign.

The immune system then attacks the foreign nature ...

The hordes of bark beetles that have bored their way through more than six billion trees in the western United States and British Columbia since the 1990s do more than kill stately pine, spruce and other trees.

Results of a new study show that these pests can make trees release up to 20 times more of the organic substances that foster haze and air pollution in forested areas.

A paper reporting the findings appears today in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, published by the American Chemical Society.

Scientists Kara Huff Hartz of Southern Illinois University ...

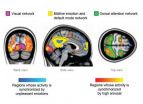

Experiencing strong emotions synchronises brain activity across individuals, research team at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre in Finland has revealed.

Human emotions are highly contagious. Seeing others' emotional expressions such as smiles triggers often the corresponding emotional response in the observer. Such synchronisation of emotional states across individuals may support social interaction: When all group members share a common emotional state, their brains and bodies process the environment in a similar fashion.

Researchers at Aalto University and ...

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), in cooperation with medical and patient societies from throughout Latin America, has today published a landmark report which compiles osteoporosis-related data on 14 countries and the region as a whole. The report shows that fragility fractures due to osteoporosis are predicted to more than double in some countries in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, which literally means 'porous bones', is a disease which causes bones to become fragile and more likely to break. Older adults, and post-menopausal women in particular, are ...

A new Audit report on fragility fractures, issued today by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), predicts that Brazil will experience an explosion in the number of fragility fractures due to osteoporosis in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, a disease which weakens bones and makes them more likely to fracture, is thought to affect around 33% of postmenopausal women in Brazil. Fractures due to osteoporosis mostly affect older adults, with fractures at the spine and hip causing the most suffering, disability and healthcare expenditure.

Currently, about 20% ...

Sensors that work flawlessly in laboratory settings may stumble when it comes to performing in real-world conditions, according to researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

These shortcomings are important as they relate to safeguarding the nation's food and water supplies, said Ali Passian, lead author of a Perspective paper published in ACS Nano. In their paper, titled "Critical Issues in Sensor Science to Aid Food and Water Safety," the researchers observe that while sensors are becoming increasingly sophisticated, little or no field ...