Pivotal role for proteins -- from helping turn carbs into energy to causing devastating disease

Study identifies proteins' critical function in cellular and disease processes

2012-05-28

(Press-News.org) (SALT LAKE CITY)—Research into how carbohydrates are converted into energy has led to a surprising discovery with implications for the treatment of a perplexing and potentially fatal neuromuscular disorder and possibly even cancer and heart disease.

Until this study, the cause of this neuromuscular disorder was unknown. But after obtaining DNA from three families with members who have the disorder, a team led by University of Utah scientists Jared Rutter, Ph.D., associate professor of biochemistry and Carl Thummel, Ph.D., professor of human genetics, sequenced two genes and identified two mutations that cause this devastating disease.

"The ability to convert carbohydrates into energy is critical for people and other organisms to live. But when that process goes awry, potentially fatal health problems can occur," Rutter says. "If we can figure out a way to correct the defects, we might be able to treat the disease."

Rutter and Thummel are senior authors on a study published online in Science Express on Thursday, May 24, 2012.

The researchers studied two proteins, Mpc1 and Mpc2, which are among a dozen proteins they looked at in fruit flies, yeast, and then humans. They discovered that the two proteins play a pivotal role in the cellular process that produces the majority of ATP, a molecule that is the main source of energy for cells and is essential for people and other animals to live. Rutter and his colleagues also discovered that when Mpc1 and Mpc2 are impaired they cause the deadly and as of yet unnamed neuromuscular disorder. This disorder affects thousands of people worldwide.

To produce ATP, the body metabolizes carbohydrates and converts them into pyruvate, which then typically enters into the mitochondria in cells. Once inside the mitochondria—a self-contained unit often referred to as a cellular power plant—pyruvate is consumed in the production of ATP. Rutter and his fellow researchers discovered that Mpc1 and Mpc2 are critical for pyruvate entry into mitochondria. When Mpc1 and Mpc2 are eliminated or mutated, pyruvate cannot enter into mitochondria and ATP is not efficiently produced – and that's when serious health problems can arise, including the neuromuscular disorder that in its most severe forms is deadly.

The ramifications of this study go beyond the production of ATP and birth defects seen in the neuromuscular disorder. The findings may be useful in understanding some of the metabolic defects associated with cancer and heart disease, according to Rutter. Cancer cells typically don't consume their pyruvate in the production of ATP at the same rate as normal cells. Instead, they convert the pyruvate to lactate. This property of cancer cells is called the Warburg Effect and is named after Nobel laureate and cancer researcher Otto Heinrich Warburg. Some forms of heart disease have a similar problem.

Further study based on the current research may provide important information regarding those diseases, according to Rutter. "That might be the most important outcome of our studies in the long run," he says.

The study's first author is Daniel K. Bricker, a doctoral student in human genetics at the University of Utah. Researchers from Harvard University, and the Laboratoire de Biochimie and the Institut de Genetique et de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, both in France, also contributed to the study.

INFORMATION: END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2012-05-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. — There's nothing like a new pair of eyeglasses to bring fine details into sharp relief. For scientists who study the large molecules of life from proteins to DNA, the equivalent of new lenses have come in the form of an advanced method for analyzing data from X-ray crystallography experiments.

The findings, just published in the journal Science, could lead to new understanding of the molecules that drive processes in biology, medical diagnostics, nanotechnology and other fields.

Like dentists who use X-rays to find tooth decay, scientists use X-rays ...

2012-05-28

Research from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that the human olfactory bulb – a structure in the brain that processes sensory input from the nose – differs from that of other mammals in that no new neurons are formed in this area after birth. The discovery, which is published in the scientific journal Neuron, is based on the age-determination of the cells using the carbon-14 method, and might explain why the human sense of smell is normally much worse than that of other animals.

"I've never been so astonished by a scientific discovery," says lead investigator Jonas ...

2012-05-28

A new type of male contraceptive could be created thanks to the discovery of a key gene essential for sperm development.

The finding could lead to alternatives to conventional male contraceptives that rely on disrupting the production of hormones, such as testosterone and can cause side-effects such as irritability, mood swings and acne.

Research, led by the University of Edinburgh, has shown how a gene – Katnal1 – is critical to enable sperm to mature in the testes.

If scientists can regulate the Katnal1 gene in the testes, they could prevent sperm from maturing ...

2012-05-28

A research team led by the University of Melbourne and Monash University, Australia, has discovered why people can develop life-threatening allergies after receiving treatment for conditions such as epilepsy and AIDS.

The finding could lead to the development of a diagnostic test to determine drug hypersensitivity.

The study published today in the journal Nature, revealed how some drugs inadvertently target the immune system to alter how the body's immune system perceives it's own tissues, making them look foreign.

The immune system then attacks the foreign nature ...

2012-05-28

The hordes of bark beetles that have bored their way through more than six billion trees in the western United States and British Columbia since the 1990s do more than kill stately pine, spruce and other trees.

Results of a new study show that these pests can make trees release up to 20 times more of the organic substances that foster haze and air pollution in forested areas.

A paper reporting the findings appears today in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, published by the American Chemical Society.

Scientists Kara Huff Hartz of Southern Illinois University ...

2012-05-28

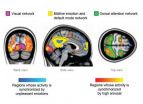

Experiencing strong emotions synchronises brain activity across individuals, research team at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre in Finland has revealed.

Human emotions are highly contagious. Seeing others' emotional expressions such as smiles triggers often the corresponding emotional response in the observer. Such synchronisation of emotional states across individuals may support social interaction: When all group members share a common emotional state, their brains and bodies process the environment in a similar fashion.

Researchers at Aalto University and ...

2012-05-28

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), in cooperation with medical and patient societies from throughout Latin America, has today published a landmark report which compiles osteoporosis-related data on 14 countries and the region as a whole. The report shows that fragility fractures due to osteoporosis are predicted to more than double in some countries in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, which literally means 'porous bones', is a disease which causes bones to become fragile and more likely to break. Older adults, and post-menopausal women in particular, are ...

2012-05-28

A new Audit report on fragility fractures, issued today by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), predicts that Brazil will experience an explosion in the number of fragility fractures due to osteoporosis in the coming decades.

Osteoporosis, a disease which weakens bones and makes them more likely to fracture, is thought to affect around 33% of postmenopausal women in Brazil. Fractures due to osteoporosis mostly affect older adults, with fractures at the spine and hip causing the most suffering, disability and healthcare expenditure.

Currently, about 20% ...

2012-05-28

Sensors that work flawlessly in laboratory settings may stumble when it comes to performing in real-world conditions, according to researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

These shortcomings are important as they relate to safeguarding the nation's food and water supplies, said Ali Passian, lead author of a Perspective paper published in ACS Nano. In their paper, titled "Critical Issues in Sensor Science to Aid Food and Water Safety," the researchers observe that while sensors are becoming increasingly sophisticated, little or no field ...

2012-05-28

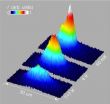

Physicists have trapped and cooled exotic particles called excitons so effectively that they condensed and cohered to form a giant matter wave.

This feat will allow scientists to better study the physical properties of excitons, which exist only fleetingly yet offer promising applications as diverse as efficient harvesting of solar energy and ultrafast computing.

"The realization of the exciton condensate in a trap opens the opportunity to study this interesting state. Traps allow control of the condensate, providing a new way to study fundamental properties of light ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Pivotal role for proteins -- from helping turn carbs into energy to causing devastating disease

Study identifies proteins' critical function in cellular and disease processes