(Press-News.org) Fighting "superbugs" – strains of pathogenic bacteria that are impervious to the antibiotics that subdued their predecessor generations – has required physicians to seek new and more powerful drugs for their arsenals. Unfortunately, in time, these treatments also can fall prey to the same microbial ability to become drug resistant. Now, a research team at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) may have found a way to break the cycle that doesn't demand the deployment of a next-generation medical therapy: preventing "superbugs" from genetically propagating drug resistance.

The team will present their findings at the annual meeting of the American Crystallographic Association, held July 28 – Aug. 1 in Boston, Mass.

For years, the drug vancomycin has been the last-stand treatment for life-threatening cases of methicilin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA. A powerful antibiotic first isolated in 1953 from soil collected in the jungles of Borneo, vancomycin works by inhibiting formation of the S. aureus cell wall so that it cannot provide structural support and protection. In 2002, however, a strain of S. aureus was isolated from a diabetic kidney dialysis patient that would not succumb to vancomycin. This was the first recorded instance in the United States of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or VRSA, a deadly variant that many now consider one of the most dangerous bacteria in the world.

Former UNC graduate student Jonathan Edwards (now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), under the guidance of chemistry professor Matthew Redinbo, led the research team that sought a detailed biochemical understanding of the VRSA threat. They focused on a S. aureus plasmid—a circular loop of double-stranded DNA within the Staph cell separate from the genome—called plW1043 that codes for drug resistance and can be transferred via conjugation ("mating" that involves genetic material passing through a tube from a donor bacterium to a recipient).

Before the plasmid gene for drug resistance can be passed, it must be processed for the transfer. This occurs when a protein called the Nicking Enzyme of Staphylococci, or NES, binds with its active area, known as the relaxase region, to the donor cell plasmid. NES then cuts, or "nicks," one strand of the double helix so that it separates into two single strands of DNA. One moves into the recipient cell while the other remains with the donor. After the two strands are replicated, NES reforms the plasmid in both cells, creating two drug-resistant Staph that are ready to spread their misery further.

Using x-ray crystallography, Edwards, Redinbo and their colleagues defined the structure of both ends of the VRSA NES protein, the N-terminus where the relaxase region resides and the molecule's opposite end known as the C-terminus. They noticed that the N-terminus structure included a region with two distinct protein loops. Suspecting that this area might play a critical role in the VRSA plasmid transfer process, the researchers cut out the loops. This kept the NES relaxase region from clamping onto or staying bound to the plasmid DNA.

Biochemical assays showed that the function of the loops was indeed to keep the relaxase region attached to the plasmid until nicking occurred. This took place, the researchers learned, in the minor groove of a specific DNA sequence on the plasmid.

"We realized that a compound that could block this groove, prevent the NES loops from attaching and inhibit the cleaving of the plasmid DNA into single strands could potentially stop conjugal transfer of drug resistance altogether," Edwards says.

To test their theory in the laboratory, the researchers used a Hoechst compound—a blue fluorescent dye used to stain DNA—that could bind to the minor groove. As predicted, blocking the grove prevented nicking of the plasmid DNA sequence.

Redinbo says that this "proof of concept" experiment suggests that the same inhibition might be possible in vivo. "Perhaps by targeting the DNA minor groove, we might make antibiotics more effective against VRSA and other drug-resistant bacteria," he says.

###

This news release was prepared for the American Crystallographic Association (ACA) by the American Institute of Physics (AIP).

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE 2012 ACA MEETING

The ACA is the largest professional society for crystallography in the United States, and this is its main meeting. All scientific sessions, workshops, poster sessions, and events will be held at the Westin Waterfront Hotel in Boston, Mass.

USEFUL LINKS:

Main meeting website:

http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-meeting-homepage

Meeting program:

http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-tentative-program

Meeting abstracts:

http://www.amercrystalassn.org/app/sessions

Exhibits:

http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-exhibits

ABOUT ACA

The American Crystallographic Association (ACA) was founded in 1949 through a merger of the American Society for X-Ray and Electron Diffraction (ASXRED) and the Crystallographic Society of America (CSA). The objective of the ACA is to promote interactions among scientists who study the structure of matter at atomic (or near atomic) resolution. These interactions will advance experimental and computational aspects of crystallography and diffraction. They will also promote the study of the arrangements of atoms and molecules in matter and the nature of the forces that both control and result from them.

Researchers unveil molecular details of how bacteria propagate antibiotic resistance

2012-07-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Climate concerns

2012-07-27

For decades, scientists have known that the effects of global climate change could have a potentially devastating impact across the globe, but Harvard researchers say there is now evidence that it may also have a dramatic impact on public health.

As reported in a paper published in the July 27 issue of Science, a team of researchers led by James G. Anderson, the Philip S. Weld Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry, are warning that a newly-discovered connection between climate change and depletion of the ozone layer over the U.S. could allow more damaging ultraviolet (UV) ...

Research links sexual imagery and consumer impatience

2012-07-27

How do sexual cues affect consumer behavior? New research from USC Marshall School of Business Assistant Professor of Marketing Kyu Kim and Gal Zauberman, associate professor of marketing at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, reveals the reasons why sexual cues cause us to be impatient and can affect monetary decisions.

Their paper, "Can Victoria's Secret Change the Future: A Subjective Time Perception Account of Sexual Cue Effects on Impatience," departs from earlier theories indicating that impatience in response to sexual cues is solely an outcome ...

NIH team describes protective role of skin microbiota

2012-07-27

WHAT:

A research team at the National Institutes of Health has found that bacteria that normally live in the skin may help protect the body from infection. As the largest organ of the body, the skin represents a major site of interaction with microbes in the environment.

Although immune cells in the skin protect against harmful organisms, until now, it has not been known if the millions of naturally occurring commensal bacteria in the skin—collectively known as the skin microbiota—also have a beneficial role. Using mouse models, the NIH team observed that commensals ...

Telephone therapy technique brings more Iraq and Afghanistan veterans into mental health treatment

2012-07-27

A brief therapeutic intervention called motivational interviewing, administered over the telephone, was significantly more effective than a simple "check-in" call in getting Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans with mental health diagnoses to begin treatment for their conditions, in a study led by a physician at the San Francisco VA Medical Center and the University of California, San Francisco.

Participants receiving telephone motivational interviewing also were significantly more likely to stay in therapy, and reported reductions in marijuana use and a decreased sense ...

Breast cancer patients who lack RB gene respond better to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

2012-07-27

PHILADELPHIA—Breast cancer patients whose tumors lacked the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene (RB) had an improved pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, researchers at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and the Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson report in a retrospective study published in a recent online issue of Clinical Cancer Research.

Many breast cancer patients undergo neoadjuvant therapy to reduce the size or extent of the cancer before surgical intervention. Complete response of the tumor to such treatment signifies an improved overall prognosis. ...

Solving the mystery of how cigarette smoking weakens bones

2012-07-27

Almost 20 years after scientists first identified cigarette smoking as a risk factor for osteoporosis and bone fractures, a new study is shedding light on exactly how cigarette smoke weakens bones. The report, in ACS' Journal of Proteome Research, concludes that cigarette smoke makes people produce excessive amounts of two proteins that trigger a natural body process that breaks down bone.

Gary Guishan Xiao and colleagues point out that previous studies suggested toxins in cigarette smoke weakened bones by affecting the activity of osteoblasts, cells which build new bone, ...

Alcohol could intensify the effects of some drugs in the body

2012-07-27

Scientists are reporting another reason — besides possible liver damage, stomach bleeding and other side effects — to avoid drinking alcohol while taking certain medicines. Their report in ACS' journal Molecular Pharmaceutics describes laboratory experiments in which alcohol made several medications up to three times more available to the body, effectively tripling the original dose.

Christel Bergström and colleagues explain that beverage alcohol, or ethanol, can cause an increase in the amount of non-prescription and prescription drugs that are "available" to the body ...

A new genre of diagnostic tests for the era of personalized medicine

2012-07-27

A new genre of medical tests – which determine whether a medicine is right for a patient's genes – are paving the way for increased use of personalized medicine, according to the cover story in the current edition of Chemical & Engineering News. C&EN is the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific society.

Celia Henry Arnaud, C&EN senior editor, points out that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several precedent-setting cancer drugs that provide a glimpse of the "personalized" medical care that awaits patients ...

The first robot that mimics the water striders' jumping abilities

2012-07-27

The first bio-inspired microrobot capable of not just walking on water like the water strider – but continuously jumping up and down like a real water strider – now is a reality. Scientists reported development of the agile microrobot, which could use its jumping ability to avoid obstacles on reconnaissance or other missions, in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Qinmin Pan and colleagues explain that scientists have reported a number of advances toward tiny robots that can walk on water. Such robots could skim across lakes and other bodies of water to monitor water ...

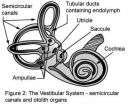

Decoding the secrets of balance

2012-07-27

If you have ever looked over the edge of a cliff and felt dizzy, you understand the challenges faced by people who suffer from symptoms of vestibular dysfunction such as vertigo and dizziness. There are over 70 million of them in North America. For people with vestibular loss, performing basic daily living activities that we take for granted (e.g. dressing, eating, getting in and out of bed, getting around inside as well as outside the home) becomes difficult since even small head movements are accompanied by dizziness and the risk of falling.

We've known for a while ...