(Press-News.org) The rare disorder Wolfram syndrome is caused by mutations in a single gene, but its effects on the body are far reaching. The disease leads to diabetes, hearing and vision loss, nerve cell damage that causes motor difficulties, and early death.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston and the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research report that they have identified a mechanism related to mutations in the WFS1 gene that affects insulin-secreting beta cells. The finding will aid in the understanding of Wolfram syndrome and also may be important in the treatment of milder forms of diabetes and other disorders.

The study is published online in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

"We found something we didn't expect," says researcher Fumihiko Urano, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine in Washington University's Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research. "The study showed that the WFS1 gene is crucial to producing a key molecule involved in controlling the metabolic activities of individual cells." That molecule is called cyclic AMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate).

In insulin-secreting beta cells in the pancreas, for example, cyclic AMP rises in response to high blood sugar, causing those cells to produce and secrete insulin.

AUDIO:

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and elsewhere have identified a cellular mechanism that allows a single gene to cause damage in many different systems in...

Click here for more information.

"I would compare cyclic AMP to money," Urano says. "You can't just take something you make to the store and use it to buy food. First, you have to convert it into money. Then, you use the money to buy food. In the body, external signals stimulate a cell to make cyclic AMP, and then the cyclic AMP, like money, can 'buy' insulin or whatever else may be needed."

The reason patients with Wolfram syndrome experience so many problems, he says, is because mutations in the WFS1 gene interfere with cyclic AMP production in beta cells in the pancreas.

"In patients with Wolfram syndrome, there is no available WFS1 protein, and that protein is key in cyclic AMP production," he explains. "Then, because levels of cyclic AMP are low in insulin-secreting beta cells, those cells produce and secrete less insulin. And in nerve cells, less cyclic AMP can lead to nerve cell dysfunction and death."

By finding that cyclic AMP production is affected by mutations in the WFS1 gene, researchers now have a potential target for understanding and treating Wolfram syndrome.

"I don't know whether we can find a way to control cyclic AMP production in specific tissues," he says. "But if that's possible, it could help a great deal."

Meanwhile, although Wolfram syndrome is rare, affecting about 1 in 500,000 people, Urano says the findings also may be important to more common disorders.

"It's likely this mechanism is related to diseases such as type 2 diabetes," he says. "If a complete absence of the WFS1 protein causes Wolfram syndrome, perhaps a partial impairment leads to something milder, like diabetes."

INFORMATION:

Fonseca SG, Urano F, Weir GC, Gromada J, Burcin M. Wolfram syndrome 1 and adenylyl cyclase 8 interact at the plasma membrane to regulate insulin production and secretion. Nature Cell Biology, Advance Online Publication, Sept. 16, 2012.

Funding for this research comes from the JDRF, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH grant numbers DK067493, DK016746, P60 DK020579, RR024992, and UL1 TR000448.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Researchers identify mechanism that leads to diabetes, blindness

2012-09-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Drug combination against NRAS-mutant melanoma discovered

2012-09-17

HOUSTON – A new study published online in Nature Medicine, led by scientists at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, describes the discovery of a novel drug combination aimed at a subset of melanoma patients who currently have no effective therapeutic options.

Melanoma patients have different responses to therapy, depending on what genes are mutated in their tumors. About half of melanomas have a mutation in the BRAF gene; while a quarter have a mutation in the NRAS gene.

New BRAF inhibitor drugs are effective against BRAF-mutant melanoma, but no comparable ...

Young researcher on the trail of herbal snakebite antidote

2012-09-17

A PhD student at the University of Copenhagen has drawn on nature's own pharmacy to help improve the treatment of snakebites in Africa.

Marianne Molander from the University of Copenhagen's Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences has been working within a Danish team that has examined various plants native to the African continent in a bid to find locally available herbal antidotes.

"Snake venom antidotes are expensive, it's often a long way to the nearest doctor and it can be difficult to store the medicine properly in the warm climate. As a result many local people ...

No increased risk of cancer for people with shingles

2012-09-17

Herpes zoster, or shingles, does not increase the risk of cancer in the general population, according to a study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Although herpes zoster is more common in patients with cancer than in those without, it is unknown whether the risk of cancer is increased for people with herpes zoster. Several studies have indicated an association although most were conducted in western countries.

A large study of 35 871 patients in Taiwan with newly diagnosed herpes zoster found no increased risk of cancer in patients with herpes zoster.

"We ...

Adequate sleep helps weight loss

2012-09-17

Adequate sleep is an important part of a weight loss plan and should be added to the recommended mix of diet and exercise, states a commentary in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Although calorie restriction and increased physical activity are recommended for weight loss, there is significant evidence that inadequate sleep is contributing to obesity. Lack of sleep increases the stimulus to consume more food and increases appetite-regulating hormones.

"The solution [to weight loss] is not as simple as 'eat less, move more, sleep more,'" write Drs. Jean-Phillippe ...

Canada needs approach to combat elder abuse

2012-09-17

Canada needs a comprehensive approach to reduce elder abuse that includes financial supports and programs for seniors and their caregivers, argues an editorial in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

In Canada, an estimated 4% of seniors — 200 000 to 500 000 people — experience some form of abuse or neglect.

"The broader solution lies in a more comprehensive approach that requires the support of government and the Canadian health care system," writes Barbara Sibbald, deputy editor, CMAJ with Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, associate professor, Geriatric Medicine Section, ...

JCI early table of contents for Sept. 17, 2012

2012-09-17

A non-invasive method to track Huntington's disease progression

Huntington's disease is a fatal, inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding huntingtin. Expresion of mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein is correlated with the onset and progression of the disease and new therapies are being developed to reduce the expression of mHTT. In order to evaluate these new therapies, researchers need to be able to quantify the amount of mHTT in a particular patient; however, non-invasive quantification of mHTT isn't currently possible. In this issue ...

A non-invasive method to track Huntington's disease progression

2012-09-17

Huntington's disease is a fatal, inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding huntingtin. Expresion of mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein is correlated with the onset and progression of the disease and new therapies are being developed to reduce the expression of mHTT. In order to evaluate these new therapies, researchers need to be able to quantify the amount of mHTT in a particular patient; however, non-invasive quantification of mHTT isn't currently possible. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers led by Sarah ...

Report: Cancer now leading cause of death in US hispanics

2012-09-17

ATLANTA –September 17, 2012– A new report from American Cancer Society researchers finds that despite declining death rates, cancer has surpassed heart disease as the leading cause of death among Hispanics in the U.S. In 2009, the most recent year for which actual data are available, 29,935 people of Hispanic origin in the U.S. died of cancer, compared to 29,611 deaths from heart disease. Among non-Hispanic whites and African Americans, heart disease remains the number one cause of death.

The figures come from Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos 2012-2014, appearing ...

Scientists reveal how natural antibiotic kills tuberculosis bacterium

2012-09-17

HEIDELBERG, 17 September 2012 – A natural product secreted by a soil bacterium shows promise as a new drug to treat tuberculosis report scientists in a new study published in EMBO Molecular Medicine. A team of scientists working in Switzerland has shown how pyridomycin, a natural antibiotic produced by the bacterium Dactylosporangium fulvum, works. This promising drug candidate is active against many of the drug-resistant types of the tuberculosis bacterium that no longer respond to treatment with the front-line drug isoniazid.

"Nature and evolution have equipped some ...

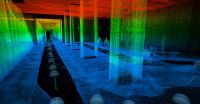

Improved positioning indoors

2012-09-17

The NAVVIS positioning system is primarily based on visual information. The TUM researchers had to develop a special location recognition system for this project. They started by taking photos of a building, simultaneously mapping prominent features like stairs and signs. A smartphone app then lets users view the map images to find their current location. All they have to do is take a photo of their surroundings. The program then compares the photo with the images stored in its database and works out the user's exact position (down to the nearest meter) and the direction ...