(Press-News.org) MADISON — High levels of family stress in infancy are linked to differences in everyday brain function and anxiety in teenage girls, according to new results of a long-running population study by University of Wisconsin-Madison scientists.

The study highlights evidence for a developmental pathway through which early life stress may drive these changes. Here, babies who lived in homes with stressed mothers were more likely to grow into preschoolers with higher levels of cortisol, a stress hormone. In addition, these girls with higher cortisol also showed less communication between brain areas associated with emotion regulation 14 years later. Last, both high cortisol and differences in brain activity predicted higher levels of adolescent anxiety at age 18.

The young men in the study did not show any of these patterns.

"We wanted to understand how stress early in life impacts patterns of brain development which might lead to anxiety and depression," says first author Dr. Cory Burghy of the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior. "Young girls who, as preschoolers, had heightened cortisol levels, go on to show lower brain connectivity in important neural pathways for emotion regulation - and that predicts symptoms of anxiety during adolescence."

To test this, scans designed by Dr. Rasmus Birn, assistant professor of psychiatry in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, showed that teenage girls whose mothers reported high levels of family stress when the girls were babies show reduced connections between the amygdala or threat center of the brain and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain responsible for emotional regulation. Birn used a method called resting-state functional connectivity (fcMRI), which looks at the brain connections while the brain is at a resting state.

The study is being published today in Nature Neuroscience.

"Merging field research and home observation with the latest laboratory measures really makes this study novel," says Dr. Richard Davidson, professor of psychology and psychiatry, and director of the lab where Burghy is a post-doctoral researcher. "This will pave the way to better understanding of how the brain develops, and could give us insight into ways to intervene when children are young."

The current paper has its roots back in 1990 and 1991, when 570 children and their families enrolled in the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work (WSFW). All of the children were born in either Madison or Milwaukee. Dr. Marilyn Essex, a UW professor of psychiatry and co-director of the WSFW, said the initial goal was to study the effects of maternity leave, day care and other factors on family stress. Over the years, the study has resulted in important findings on the social, psychological, and biological risk factors for child and adolescent mental health problems. Subjects are now 21 and 22 years old, and many continue to participate.

For the current study, Burghy and Birn used fcMRI to scan the brains of 57 subjects – 28 female and 29 male – to map the strength of connections between the amygdala, an area of the brain known for its sensitivity to negative emotion and threat, and the prefrontal cortex, often associated with helping to process and regulate negative emotion. Then, they looked back at earlier results and found that girls with weaker connections had, as infants, lived in homes where their mothers had reported higher general levels of stress – which could include symptoms of depression, parenting frustration, marital conflict, feeling overwhelmed in their role as a parent, and/or financial stress. As four-year-olds, these girls also showed higher levels of cortisol late in the day, measured in saliva, which is thought to demonstrate the stress the children experienced over the course of that day.

Near the time of the scan, researchers queried the teenagers about their anxiety symptoms, and about the stress in their current lives. They found a connection with childhood stress, rather than current stress levels. This suggested that higher cortisol levels in childhood could have modified the girl's developing brain, leaving weaker connections between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala – an association that explained about 65 percent of the variance in teenage anxiety levels.

"Our findings raise questions on how boys and girls differ in the life impact of early stress,'' says Davidson, who calls the disparity unsurprising. "We do know that women report higher levels of mood and anxiety disorders, and these sex-based differences are very pronounced, especially in adolescence."

Davidson says the study "raises important questions to help guide clinicians in preventive strategies that could benefit all children by teaching them to propagate well-being and resilience."

Essex notes that some of the recent results also answer questions raised when the newborns were enrolled a generation ago.

"Now that we are showing that early life stress and cortisol affect brain development," she says, "it raises important questions about what we can do to better support young parents and families."

INFORMATION:

Other members of the Wisconsin study team are Diane Stodola, Andrea Hayes and Michelle Fox, of the Waisman laboratory; and Dr. Paula Ruttle, Erin Molloy, Jeffrey Armstrong, Dr. Jonathan Oler, and Dr. Ned Kalin, of the psychiatry department. Many of them are also on the staff of the UW Conte Adolescence Center.

This most recent study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development.

END

China's endangered wild pandas may need new dinner reservations – and quickly – based on models that indicate climate change may kill off swaths of bamboo that pandas need to survive.

In this week's international journal Nature Climate Change, scientists from Michigan State University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences give comprehensive forecasts of how changing climate may affect the most common species of bamboo that carpet the forest floors of prime panda habitat in northwestern China. Even the most optimistic scenarios show that bamboo die-offs would effectively ...

PHILADELPHIA - Fat cells store excess energy and signal these levels to the brain. In a new study this week in Nature Medicine, Georgios Paschos PhD, a research associate in the lab of Garret FitzGerald, MD, FRS director of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, shows that deletion of the clock gene Arntl, also known as Bmal1, in fat cells, causes mice to become obese, with a shift in the timing of when this nocturnal species normally eats. These findings shed light on the complex causes of obesity ...

How can solar energy be stored so that it can be available any time, day or night, when the sun shining or not? EPFL scientists are developing a technology that can transform light energy into a clean fuel that has a neutral carbon footprint: hydrogen. The basic ingredients of the recipe are water and metal oxides, such as iron oxide, better known as rust. Kevin Sivula and his colleagues purposefully limited themselves to inexpensive materials and easily scalable production processes in order to enable an economically viable method for solar hydrogen production. The device, ...

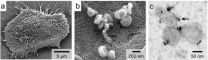

ANN ARBOR—A thin, flexible electrode developed at the University of Michigan is 10 times smaller than the nearest competition and could make long-term measurements of neural activity practical at last.

This kind of technology could eventually be used to send signals to prosthetic limbs, overcoming inflammation larger electrodes cause that damages both the brain and the electrodes.

The main problem that neurons have with electrodes is that they make terrible neighbors. In addition to being enormous compared to the neurons, they are stiff and tend to rub nearby cells ...

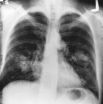

An international group of scientists has identified three genetic regions that predispose Asian women who have never smoked to lung cancer. The finding provides further evidence that risk of lung cancer among never-smokers, especially Asian women, may be associated with certain unique inherited genetic characteristics that distinguishes it from lung cancer in smokers.

Lung cancer in never-smokers is the seventh leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and the majority of lung cancers diagnosed historically among women in Eastern Asia have been in women who never smoked. ...

A novel miniature diagnostic platform using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology is capable of detecting minuscule cell particles known as microvesicles in a drop of blood. Microvesicles shed by cancer cells are even more numerous than those released by normal cells, so detecting them could prove a simple means for diagnosing cancer. In a study published in Nature Medicine, investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Systems Biology (CSB) demonstrate that microvesicles shed by brain cancer cells can be reliably detected in human blood through ...

SEATTLE – An international research team co-led by a scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has identified two genetic factors behind the third most common form of muscular dystrophy. The findings, published online in Nature Genetics, represent the latest in the team's series of groundbreaking discoveries begun in 2010 regarding the genetic causes of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, or FSHD.

The team, co-led by Stephen Tapscott, M.D., Ph.D., a member of the Hutchinson Center's Human Biology Division, discovered that a rare variant of FSHD, called type ...

Nobody knows the remarkable properties of human skin like the researchers struggling to emulate it. Not only is our skin sensitive, sending the brain precise information about pressure and temperature, but it also heals efficiently to preserve a protective barrier against the world. Combining these two features in a single synthetic material presented an exciting challenge for Stanford Chemical Engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team.

Now, they have succeeded in making the first material that can both sense subtle pressure and heal itself when torn or cut. Their ...

This press release is available in German.

Using the world's most powerful X-ray laser in California, an international research team discovered a surprising behaviour of atoms: with a single X-ray flash, the group led by Daniel Rolles from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) in Hamburg (Germany) was able to kick a record number of 36 electrons at once out of a xenon atom. According to theoretical calculations, these are significantly more than should be possible at this energy of the X-ray radiation. The team present their unexpected observations in the ...

Scientists from the University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) published a study today in Nature Climate Change showing that besides marine inundation (flooding), low-lying coastal areas may also be vulnerable to "groundwater inundation," a factor largely unrecognized in earlier predictions on the effects of sea level rise (SLR). Previous research has predicted that by the end of the century, sea level may rise 1 meter. Kolja Rotzoll, Postdoctoral Researcher at the UHM Water Resources Research Center and Charles Fletcher, UHM Associate Dean, found that the flooded area in urban ...