Johns Hopkins scientists use Pap test fluid to detect ovarian, endometrial cancers

2013-01-10

(Press-News.org) Using cervical fluid obtained during routine Pap tests, scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center have developed a test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. In a pilot study, the "PapGene" test, which relies on genomic sequencing of cancer-specific mutations, accurately detected all 24 (100 percent) endometrial cancers and nine of 22 (41 percent) ovarian cancers. Results of the experiments are published in the January 9 issue of the journal, Science Translational Medicine.

The investigators note that larger scale studies are needed before clinical implementation can begin, but they believe the test has the potential to pioneer genomic-based cancer screening tests.

The Papanicolaou (Pap) test, during which cells collected from the cervix are examined for microscopic signs of cancer, is widely and successfully used to screen for cervical cancers. However, no routine screening method is available for ovarian or endometrial cancers.

Since the Pap test occasionally contains cells shed from the ovaries or endometrium, cancer cells arising from these organs could be present in the fluid as well, says Luis Diaz, M.D., associate professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins and director of the Swim Across America Laboratory. The Laboratory is sponsored by a volunteer organization that raises funds for cancer research. "Our genomic sequencing approach may offer the potential to detect these cancer cells in a scalable and cost effective way," adds Diaz.

Cervical fluid of patients with gynecologic cancer carries normal cellular DNA mixed together with DNA from cancer cells, according to the investigators. Their task was to use genomic sequencing to distinguish cancerous from normal DNA.

The scientists had to determine the most common genetic changes in ovarian and endometrial cancers in order to prioritize which genomic regions to include in their test. They searched publically-available genome-wide studies of ovarian cancer, including those done by other Johns Hopkins investigators, to find ovarian-cancer specific mutations. Such genome-wide studies were not available for the most common type of endometrial cancer, so they conducted genome-wide sequencing studies on 22 of these endometrial cancers.

From the ovarian and endometrial cancer genome data, the Johns Hopkins-led team identified 12 of the most frequently mutated genes in both cancers and developed the PapGene test with this insight in mind.

The investigators then applied PapGene on Pap test samples from ovarian and endometrial cancer patients at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil and ILSBio, a tissue bank. The new test detected both early and late stage disease in the endometrial and ovarian cancers tested. No healthy women in the control group were misclassified as having cancer.

The investigators' next steps include applying PapGene on more samples and working to increase the test's sensitivity in detecting ovarian cancer. "Performing the test at different times during the menstrual cycle, inserting the cervical brush deeper into the cervical canal, and assessing more regions of the genome may boost the sensitivity," says Chetan Bettegowda, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins.

Together, ovarian and endometrial cancers are diagnosed in nearly 70,000 women in the United States each year, and about one-third of them will die from it. "Genomic-based tests could help detect ovarian and endometrial cancers early enough to cure more of them," says graduate student Yuxuan Wang, who notes that the cost of the test could be similar to current cervical fluid HPV testing, which is less than $100.

PapGene is a high-sensitivity approach for the detection of cancer-specific DNA mutations, according to the investigators; however, false mutations can be erroneously created during the many steps -- including amplification, sequencing, and analysis -- required to prepare the DNA collected from a Pap test specimen for sequencing. The investigators needed to build a safeguard into PapGene's sequencing method, designed to weed out artifacts that could lead to misleading test results.

"If unaccounted for, artifacts could lead to a false positive test result and incorrectly indicate that a healthy person has cancer," says graduate student Isaac Kinde.

Kinde added a unique genetic barcode -- a random set of 14 DNA base pairs -- to each DNA fragment at an initial stage of the sample preparation process. Although each DNA fragment is copied many times before eventually being sequenced, all of the newly-copied DNA can be traced back to one original DNA molecule through their genetic barcodes. If the copies originating from the same DNA molecule do not all contain the same mutation, then an artifact is suspected and the mutation is disregarded. However, bonafide mutations, which exist in the sample before the initial barcoding step, will be present in all of the copies originating from the original DNA molecule.

###

Funding for the research was provided by Swim Across America, the Commonwealth Fund, the Hilton-Ludwig Cancer Prevention Initiative, the Virgina and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the Chia Family Foundation, The Honorable Tina Brozman Foundation, The United Negro College Fund-Merck Graduate Science Dissertation Fellowship, the Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists, the National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance and the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Center (N01-CN-43309, CA129825, CA43460).

In addition to Kinde, Bettegowda, Wang and Diaz, investigators participating in the research include Jian Wu, Nishant Agrawal, Ie-Ming Shih, Robert Kurman, Robert Giuntoli, Richard Roden, James R. Eshleman from Johns Hopkins; Nickolas Papadopoulos, Kenneth Kinzler and Bert Vogelstein from the Ludwig Center at Johns Hopkins; Fanny Dao and Douglas A. Levine from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; Jesus Paula Carvalho and Suely Kazue Nagahashi Marie from the University of Sao Paulo.

Papadopoulos, Kinzler, Vogelstein and Diaz are co-founders of Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics. They own stocks in the companies and are members of their Scientific Advisory Boards. Inostics and Personal Genome Diagnostics have licensed several patent applications from Johns Hopkins. These relationships are subject to certain restrictions under The Johns Hopkins University policy, and the terms of these arrangements are managed by the University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.

On the Web:

Science Translational Medicine: http://stm.sciencemag.org/

www.hopkinskimmelcancercenter.org

Animation and illustration of PapGene is available upon request.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mapping the Milky Way: Radio telescopes give clues to structure, history

2013-01-10

Astronomers have discovered hundreds of previously-unknown sites of massive star formation in the Milky Way, including the most distant such objects yet found in our home Galaxy. Ongoing studies of these objects promise to give crucial clues about the structure and history of the Milky Way.

The scientists found regions where massive young stars or clusters of such stars are forming. These regions, which astronomers call HII (H-two) regions, serve as markers of the Galaxy's structure, including its spiral arms and central bar.

"We're vastly improving the census of our ...

Mount Sinai researchers foresee new therapies and diagnostics for deadly fibrotic diseases

2013-01-10

A team of scientists has developed a playbook for ending the devastating impact of fibrotic diseases of the liver, lung, kidney, and other organs, which are responsible for as many as 45 percent of all deaths in the industrialized world. Despite the prevalence of these illnesses, which are caused by buildup of scar tissue, there are no approved antifibrotic drugs on the market in the U.S. A top fibrosis expert from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and three other institutions have described drug targets and compounds they hope will prove broadly effective in ...

Drug-resistant melanoma tumors shrink when therapy is interrupted

2013-01-10

Researchers in California and Switzerland have discovered that melanomas that develop resistance to the anti-cancer drug vemurafenib (marketed as Zelboraf), also develop addiction to the drug, an observation that may have important implications for the lives of patients with late-stage disease.

The team, based at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research (NIBR) in Emeryville, Calif., and University Hospital Zurich, found that one mechanism by which melanoma cells become resistant to vemurafenib also renders them ...

The farthest supernova yet for measuring cosmic history

2013-01-10

What if you had a "Wayback Television Set" and could watch an entire month of ancient prehistory unfold before your eyes in real time? David Rubin of the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) presented just such a scenario to the American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting in Long Beach, CA, when he announced the discovery of a striking astronomical object: a Type Ia supernova with a redshift of 1.71 that dates back 10 billion years in time. Labeled SN SCP-0401, the supernova is exceptional for its detailed spectrum and precision ...

Spin and bias in published studies of breast cancer trials

2013-01-10

Spin and bias exist in a high proportion of published studies of the outcomes and adverse side-effects of phase III clinical trials of breast cancer treatments, according to new research published in the cancer journal Annals of Oncology [1] today (Thursday).

In the first study to investigate how accurately outcomes and side-effects are reported in breast cancer trials, researchers at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada) found that in a third of all trials that failed to show a statistically significant benefit for the treatment ...

Particles of crystalline quartz wear away teeth

2013-01-10

This press release is available in German.

Dental microwear, the pattern of tiny marks on worn tooth surfaces, is an important basis for understanding the diets of fossil mammals, including those of our own lineage. Now nanoscale research by an international multidisciplinary group that included members of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig has unraveled some of its causes. It turns out that quartz dust is the major culprit in wearing away tooth enamel. Silica phytoliths, particles produced by plants, just rub enamel, and thus have ...

First image of insulin 'docking' could lead to better diabetes treatments

2013-01-10

A landmark discovery about how insulin docks on cells could help in the development of improved types of insulin for treating both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

For the first time, researchers have captured the intricate way in which insulin uses the insulin receptor to bind to the surface of cells. This binding is necessary for the cells to take up sugar from the blood as energy.

The research team was led by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and used the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne, Australia. The study was published today in the journal Nature.

For more ...

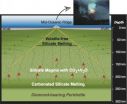

Magma in mantle has deep impact

2013-01-10

HOUSTON – (Jan. 9, 2013) – Magma forms far deeper than geologists previously thought, according to new research at Rice University.

A group led by geologist Rajdeep Dasgupta put very small samples of peridotite under very large pressures in a Rice laboratory to determine that rock can and does liquify, at least in small amounts, as deep as 250 kilometers in the mantle beneath the ocean floor. He said this explains several puzzles that have bothered scientists.

Dasgupta is lead author of the paper to be published this week in Nature.

The mantle is the planet's middle ...

After decades of research, scientists unlock how insulin interacts with cells

2013-01-10

The discovery of insulin nearly a century ago changed diabetes from a death sentence to a chronic disease.

Today a team that includes researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine announced a discovery that could lead to dramatic improvements in the lives of people managing diabetes.

After decades of speculation about exactly how insulin interacts with cells, the international group of scientists finally found a definitive answer: in an article published today in the journal Nature, the group describes how insulin binds to the cell to allow the ...

GW researchers find variation in foot strike patterns in predominantly barefoot runners

2013-01-10

WASHINGTON –A recently published paper by two George Washington University researchers shows that the running foot strike patterns vary among habitually barefoot people in Kenya due to speed and other factors such as running habits and the hardness of the ground. These results are counter to the belief that barefoot people prefer one specific style of running.

Kevin Hatala, a Ph.D. student in the Hominid Paleobiology doctoral program at George Washington, is the lead author of the paper that appears in the recent edition of the journal Public Library of Science, or PLOS ...