(Press-News.org) A new kind of pterosaur, a flying reptile from the time of the dinosaurs, has been identified by scientists from the Transylvanian Museum Society in Romania, the University of Southampton in the UK and the Museau Nacional in Rio de Janiero, Brazil.

The fossilised bones come from the Late Cretaceous rocks of Sebeş-Glod in the Transylvanian Basin, Romania, which are approximately 68 million years old. The Transylvanian Basin is world-famous for its many Late Cretaceous fossils, including dinosaurs of many kinds, as well as fossilised mammals, turtles, lizards and ancient relatives of crocodiles.

A paper on the new species, named Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis has been published in the international science journal PLoS One. Dr Darren Naish, from the University of Southampton's Vertebrate Palaeontology Research Group, who helped identify the new species, says:

"Eurazhdarcho belong to a group of pterosaurs called the azhdarchids. These were long-necked, long-beaked pterosaurs whose wings were strongly adapted for a soaring lifestyle. Several features of their wing and hind limb bones show that they could fold their wings up and walk on all fours when needed.

"With a three-metre wingspan, Eurazhdarcho would have been large, but not gigantic. This is true of many of the animals so far discovered in Romania; they were often unusually small compared to their relatives elsewhere."

The discovery is the most complete example of an azhdarchid found in Europe so far and its discovery supports a long-argued theory about the behaviour of these types of creatures.

Dr Gareth Dyke, Senior Lecturer in Vertebrate Palaeontology, based at the National Oceanography Centre Southampton says:

"Experts have argued for years over the lifestyle and behaviour of azhdarchids. It has been suggested that they grabbed prey from the water while in flight, that they patrolled wetlands and hunted in a heron or stork-like fashion, or that they were like gigantic sandpipers, hunting by pushing their long bills into mud.

"One of the newest ideas is that azhdarchids walked through forests, plains and other places in search of small animal prey. Eurazhdarcho supports this view of azhdarchids, since these fossils come from an inland, continental environment where there were forests and plains as well as large, meandering rivers and swampy regions."

Fossils from the region show that there were several places where both giant azhdarchids and small azhdarchids lived side by side. Eurazhdarcho's discovery indicates that there were many different animals hunting different prey in the region at the same time, demonstrating a much more complicated picture of the Late Cretaceous world than first thought.

###

Notes for editors:

1. The accompanying graphics show a silhouette of the known bones of Eurazhdarcho in position. Azhdarchids were able to launch into the air from a standing start, as shown in the first image (Image by Mark Witton.)

The second graphic shows a map showing places around the world where the fossils of large and small azhdarchids have been found in close proximity. It seems that many Late Cretaceous habitats were inhabited by two or even three different azhdarchid species, all differing in size and presumably in lifestyle and behaviour. Image by Mark Witton, map provided by Ron Blakey, Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Inc.

2. A copy of the paper; Mátyás Vremir, Alexander W.A. Kellner, Darren Naish, Gareth J. Dyke (2013), 'A New Azhdarchid Pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Transylvanian Basin, Romania: Implications for Azhdarchid Diversity and Distribution,' is available from Media Relations on request.

3. A further article by Darren Naish on the same topic is available online.

4. The National Oceanography Centre (NOC) is the UK's leading institution for integrated coastal and deep ocean research. NOC operates the Royal Research Ships James Cook and Discovery and develops technology for coastal and deep ocean research. Working with its partners NOC provides long-term marine science capability including: sustained ocean observing, mapping and surveying; data management and scientific advice.

The National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, is the collaborative partnership between University of Southampton and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) scientists and engineers at the Southampton Waterfront Campus.

5. The University of Southampton is a leading UK teaching and research institution with a global reputation for leading-edge research and scholarship across a wide range of subjects in engineering, science, social sciences, health and humanities.

With over 23,000 students, around 5000 staff, and an annual turnover well in excess of £435 million, the University of Southampton is acknowledged as one of the country's top institutions for engineering, computer science and medicine. We combine academic excellence with an innovative and entrepreneurial approach to research, supporting a culture that engages and challenges students and staff in their pursuit of learning.

The University is also home to a number of world-leading research centres including the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research, the Optoelectronics Research Centre, the Institute for Life Sciences, the Web Science Trust and Doctoral training Centre, the Centre for the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, the Southampton Statistical Sciences Research Institute and is a partner of the National Oceanography Centre at the Southampton waterfront campus.

For further information contact:

Charlotte Woods, Media Relations, University of Southampton, Tel: 023 8059 2128, email: C.Woods@soton.ac.uk

Catherine Beswick, Media and Communications Officer, National Oceanography Centre, Tel: 023 8059 8490, email: catherine.beswick@noc.ac.uk

www.soton.ac.uk/mediacentre/

Follow us on twitter: http://twitter.com/unisouthampton

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/unisouthampton

New kind of extinct flying reptile discovered by scientists

A new kind of pterosaur, a flying reptile from the time of the dinosaurs, has been identified by scientists from the Transylvanian Museum Society in Romania, the University of Southampton in the UK and the Museau Nacional in Rio de Janiero, Brazil

2013-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

In combat vets and others, high rate of vision problems after traumatic brain injury

2013-02-04

Philadelphia, Pa. (February 4, 2013) - Visual symptoms and abnormalities occur at high rates in people with traumatic brain injury (TBI)—including Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans with blast-related TBI, reports a study, "Abnormal Fixation in Individuals with AMD when Viewing an Image of a Face", in the February issue of Optometry and Vision Science, official journal of the American Academy of Optometry. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

Vision problems are similar for military and civilian patients with TBI, ...

Study shows Facebook unfriending has real life consequences

2013-02-04

DENVER (Feb. 4, 2013) – Unfriending someone on Facebook may be as easy as clicking a button, but a new study from the University of Colorado Denver shows the repercussions often reach far beyond cyberspace.

"People think social networks are just for fun," said study author Christopher Sibona, a doctoral student in the Computer Science and Information Systems program at the University of Colorado Denver Business School. "But in fact what you do on those sites can have real world consequences."

Sibona found that 40 percent of people surveyed said they would avoid in real ...

In a fight to the finish, Saint Louis University research aims knockout punch at hepatitis B

2013-02-04

ST. LOUIS – In research published in the Jan. 24 edition of PLOS Pathogens, Saint Louis University investigators together with collaborators from the University of Missouri and the University of Pittsburgh report a breakthrough in the pursuit of new hepatitis B drugs that could help cure the virus. Researchers were able to measure and then block a previously unstudied enzyme to stop the virus from replicating, taking advantage of known similarities with another major pathogen, HIV.

John Tavis, Ph.D., study author and professor of molecular microbiology and immunology ...

University of Leicester announces discovery of King Richard III

2013-02-04

UNIVERSITY OF LEICESTER REVEALS:

Wealth of evidence, including radiocarbon dating, radiological evidence, DNA and bone analysis and archaeological results, confirms identity of last Plantagenet king who died over 500 years ago

DNA from skeleton matches TWO of Richard III's maternal line relatives. Leicester genealogist verifies living relatives of Richard III's family

Individual likely to have been killed by one of two fatal injuries to the skull – one possibly from a sword and one possibly from a halberd

10 wounds discovered on skeleton - Richard III killed ...

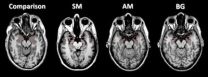

Human brain is divided on fear and panic

2013-02-04

When doctors at the University of Iowa prepared a patient to inhale a panic-inducing dose of carbon dioxide, she was fearless. But within seconds of breathing in the mixture, she cried for help, overwhelmed by the sensation that she was suffocating.

The patient, a woman in her 40s known as SM, has an extremely rare condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease that has caused extensive damage to the amygdala, an almond-shaped area in the brain long known for its role in fear. She had not felt terror since getting the disease when she was an adolescent.

In a paper published ...

New criteria for automated preschool vision screening

2013-02-04

San Francisco, CA, February 4, 2012 – The Vision Screening Committee of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, the professional organization for pediatric eye care, has revised its guidelines for automated preschool vision screening based on new evidence. The new guidelines are published in the February issue of the Journal of AAPOS.

Approximately 2% of children develop amblyopia, sometimes known as "lazy eye" – a loss of vision in one or both eyes caused by conditions that impair the normal visual input during the period of development of ...

A little tag with a large effect

2013-02-04

February 4, 2013, New York, NY and Oxford, UK – Nearly every cell in the human body carries a copy of the full human genome. So how is it that the cells that detect light in the human eye are so different from those of, say, the beating heart or the spleen?

The answer, of course, is that each type of cell selectively expresses only a unique suite of genes, actively silencing those that are irrelevant to its function. Scientists have long known that one way in which such gene-silencing occurs is by the chemical modification of cytosine—one of the four bases of DNA that ...

Shop King Jewelers 2013 Valentine's Day Jewelry Sale for Savings on Unique Valentine's Gifts & Valentine's Day Presents for Men and Women

2013-02-04

Searching for the perfect Valentine's Day gift doesn't have to be a stressful experience. King Jewelers believes that the pursuit of a unique valentine's gift for the one you love can be an enjoyable and extremely personal experience, even online. That's why for this Valentine's Day King Jewelers has put together an exclusive selection of fine jewelry, watches, diamond studs, diamond pendants and accessories for men and women that will make ideal Valentine's Day gift ideas for your loved one.

Valentines Day Gift Ideas for Him and Her

Online shoppers will find a wide ...

DNA reveals mating patterns of critically endangered sea turtle

2013-02-04

New University of East Anglia research into the mating habits of a critically endangered sea turtle will help conservationists understand more about its mating patterns.

Research published today in Molecular Ecology shows that female hawksbill turtles mate at the beginning of the season and store sperm for up to 75 days to use when laying multiple nests on the beach.

It also reveals that these turtles are mainly monogamous and don't tend to re-mate during the season.

Because the turtles live underwater, and often far out to sea, little has been understood about their ...

Changes to DNA on-off switches affect cells' ability to repair breaks, respond to chemotherapy

2013-02-04

PHILADELPHIA - Double-strand breaks in DNA happen every time a cell divides and replicates. Depending on the type of cell, that can be pretty often. Many proteins are involved in everyday DNA repair, but if they are mutated, the repair system breaks down and cancer can occur. Cells have two complicated ways to repair these breaks, which can affect the stability of the entire genome.

Roger A. Greenberg, M.D., Ph.D., associate investigator, Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute and associate professor of Cancer Biology at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

[Press-News.org] New kind of extinct flying reptile discovered by scientistsA new kind of pterosaur, a flying reptile from the time of the dinosaurs, has been identified by scientists from the Transylvanian Museum Society in Romania, the University of Southampton in the UK and the Museau Nacional in Rio de Janiero, Brazil