(Press-News.org) SEATTLE – A study of older patients with advanced head and neck cancers has found that where they were treated significantly influenced their survival.

The study, led by researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and published in the March 1 online edition of Cancer, found that patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a high number of head and neck cancers were 15 percent less likely to die of their disease as compared to patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a relatively low number of such cancers. The study also found that such patients were 12 percent less likely to die of their disease when treated at a National Cancer Institute -designated cancer center.

"Where you're treated matters," said corresponding author Eduardo Méndez, M.D., an assistant member of the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutch.

Méndez and colleagues also hypothesized that patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) who were treated at high-volume hospitals would be more likely to receive therapy that complies with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines due to the complexity of managing these cancers. Surprisingly, this was not the case, the researchers found.

According to an American Cancer Society estimate, 52,610 Americans were newly diagnosed with head and neck cancer in 2012. Many patients are diagnosed with locally advanced disease that has spread to the lymph nodes, which carries a much poorer prognosis compared to early stage disease. Patients with advanced disease require multidisciplinary management by a collaborative team comprised of multiple physician specialties and disciplines. NCCN guidelines, based on data from randomized controlled trials, recommend multimodality therapy (either surgery followed by adjuvant therapy or primary chemo-radiation) for almost all advanced cases.

The study found that despite the improved survival at high-volume hospitals, the proportion of patients who received multimodality therapy was similar – 78 percent and 79 percent – at low- and high-volume hospitals, respectively.

"NCCN guidelines are well publicized in the medical community and it was exciting to learn that clinicians at both high- and low-volume hospitals are implementing these guidelines into the complex clinical management of patients with head and neck cancer," said Méndez, who is an expert in the surgical treatment of head and neck cancer and an associate professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

"Although this study does not necessarily mean that all patients with advanced HNSCC should be treated at high-volume hospitals or at NCI-designated cancer centers, it does suggest that features of these hospitals, such as a multidisciplinary team approach or other institutional factors, play a critical role in influencing survival without influencing whether patients receive NCCN-guideline therapy," the authors concluded.

The implementation of NCCN-guideline therapy can be challenging because there are toxicities associated with these treatments that require a high level of support and infrastructure, such as that found at comprehensive cancer centers, according to Méndez.

The Hutchinson Center/University of Washington Cancer Consortium is the Pacific Northwest's only NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Patient care is provided at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, which, in partnership with Fred Hutch, UW and Seattle Children's, is a member of the NCCN.

The authors said that given the complex treatment and coordination required for patients with advanced HNSCC, suboptimal care and outcomes may be more likely in these patients compared to those who require less-complex care. In addition to their complexity, treatment modalities for advanced HNSCC have significant toxicities, which pose an additional barrier for fully implementing NCCN guideline therapy.

Prior studies in diseases other than HNSCC have shown that hospital volume and physician volume influence outcomes. However, this is the first study to examine whether hospital factors are associated with receiving multimodality therapy for patients with advanced HNSCC.

To conduct the study, researchers used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database to identify 1,195 patients age 66 and older who were diagnosed with advanced HNSCC between 2003 and 2007. Treatment modalities and survival were determined using Medicare data. Hospital volume was determined by the number of patients with HNSCC treated at each hospital.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors with Méndez included Arun Sharma, M.D., of the Department of Otolaryngology at the UW; and Stephen Schwartz, Ph.D., in the Program in Epidemiology at Fred Hutch.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and received additional support from Fred Hutch and UW.

Editor's note: The study, "Hospital Volume is Associated with Survival but not Multimodality Therapy in Medicare Patients with Advanced Head and Neck Cancer," is available online here: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.27976/full

At Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, home to three Nobel laureates, interdisciplinary teams of world-renowned scientists seek new and innovative ways to prevent, diagnose and treat cancer, HIV/AIDS and other life-threatening diseases. Fred Hutch's pioneering work in bone marrow transplantation led to the development of immunotherapy, which harnesses the power of the immune system to treat cancer with minimal side effects. An independent, nonprofit research institute based in Seattle, Fred Hutch houses the nation's first and largest cancer prevention research program, as well as the clinical coordinating center of the Women's Health Initiative and the international headquarters of the HIV Vaccine Trials Network. Private contributions are essential for enabling Fred Hutch scientists to explore novel research opportunities that lead to important medical breakthroughs. For more information visit www.fhcrc.org or follow Fred Hutch on Facebook, Twitter or YouTube.

CONTACT

Dean Forbes

206-667-2896

dforbes@fhcrc.org

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A study published in the journal Science reveals a decline in bee species since the late 1800s in West Central Illinois. The study could not have been conducted without the work of a 19th-century naturalist, says a co-author of the new research.

Charles Robertson, a self-taught entomologist who studied zoology and botany at Harvard University and the University of Illinois, was one of the first scientists to make detailed records of the interactions of wild bees and the plants they pollinate, says John Marlin, a co-author of the new analysis in Science. ...

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – In an article published as the cover story of the March 2013 issue of Nature Chemical Biology, Lindsey James, PhD, research assistant professor in the lab of Stephen Frye, Fred Eshelman Distinguished Professor in the UNC School of Pharmacy and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, announced the discovery of a chemical probe that can be used to investigate the L3MBTL3 methyl-lysine reader domain. The probe, named UNC1215, will provide researchers with a powerful tool to investigate the function of malignant brain tumor (MBT) domain ...

Colon cancer develops slowly. Precancerous lesions usually need many years to turn into a dangerous carcinoma. They are well detectable in an endoscopic examination of the colon called colonoscopy and can be removed during the same examination. Therefore, regular screening can prevent colon cancer much better than other types of cancer. Since 2002, colonoscopy is part of the national statutory cancer screening program in Germany for all insured persons aged 55 or older.

However, only one fifth of those eligible actually make use of the screening program. The reasons ...

This press release is available in French.

Montreal, March 1, 2013 – Construction in Montreal is under a microscope. Now more than ever, municipal builders need to comply with long-term urban planning goals. The difficulties surrounding massive projects like the Turcot interchange lead Montrealers to wonder if construction in this city is headed in the right direction. New research from Concordia University gives us hope that this could soon be the case if sufficient effort is made.

A team of graduate students from Concordia's Department of Geography, Planning and Environment ...

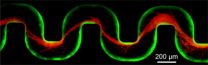

A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National ...

The bacteria that cause acne live on everyone's skin, yet one in five people is lucky enough to develop only an occasional pimple over a lifetime.

In a boon for teenagers everywhere, a UCLA study conducted with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute has discovered that acne bacteria contain "bad" strains associated with pimples and "good" strains that may protect the skin.

The findings, published in the Feb. 28 edition of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, could lead to a myriad of new therapies to ...

Ecologists have evidence that some endangered primates and large cats faced with relentless human encroachment will seek sanctuary in the sultry thickets of mangrove and peat swamp forests. These harsh coastal biomes are characterized by thick vegetation — particularly clusters of salt-loving mangrove trees — and poor soil in the form of highly acidic peat, which is the waterlogged remains of partially decomposed leaves and wood. As such, swamp forests are among the few areas in many African and Asian countries that humans are relatively less interested in exploiting (though ...

Thyroid hormone treatment administered to rats at the time of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) led to significant reduction in the loss of heart muscle cells and improvement in heart function, according to a study published by a team of researchers led by A. Martin Gerdes and Yue-Feng Chen from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, have bolstered the researchers' contention that thyroid hormones may help reduce heart damage in humans with cardiac diseases.

"I am extremely ...

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 28, 2013) – A groundbreaking new study led by the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center's Dr. Peter Zhou found that triple-negative breast cancer cells are missing a key enzyme that other cancer cells contain — providing insight into potential therapeutic targets to treat the aggressive cancer. Zhou's study is unique in that his lab is the only one in the country to specifically study the metabolic process of triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Normally, all cells — including cancerous cells — use glucose to initiate the process of making Adenosine-5'-triphosphate ...

In the nation's most diverse state, some of the sickest Californians often have the hardest time communicating with their doctors. So say the authors of a new study from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research that found that residents with limited English skills who reported the poorest health and were enrolled in commercial HMO plans were more likely to have difficulty understanding their doctors, placing this already vulnerable population at even greater risk.

The findings are significant given that, in 2009, nearly one in eight HMO enrollees in California was ...