(Press-News.org) (Boston) – A study led by researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) has identified epigenetic mechanisms that connect a variety of diseases associated with inflammation. Utilizing molecular analyses of gene expression in macrophages, which are cells largely responsible for inflammation, researchers have shown that inhibiting a defined group of proteins could help decrease the inflammatory response associated with diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and sepsis.

The study, which is published online in the Journal of Immunology, was led by first author Anna C. Belkina, MD, PhD, a researcher in the department of microbiology at BUSM, and senior author Gerald V. Denis, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology and medicine at BUSM.

Epigenetics is an emerging field of study exploring how genetically identical cells express their genes differently, resulting in different phenotypes, due to mechanisms other than DNA sequence changes.

Previous studies have shown that a gene, called Brd2, is associated with high insulin production and excessive adipose (fat) tissue expansion that drives obesity when Brd2 levels are low and cancer when Brd2 levels are high. The Brd2 gene is a member of the Bromodomain Extra Terminal (BET) family of proteins and is closely related to Brd4, which is important in highly lethal carcinomas in young people, as well as in the replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

The BET family proteins control gene expression epigenetically by acting on chromatin, the packaging material for genes, rather than on DNA directly. This mechanism of action is being explored because the interactions are not reflected in genome sequencing information or captured through DNA-based genetic analysis. In addition, this layer of gene regulation has recently been shown to be a potential target in the development of novel epigenetic drugs that could target several diseases at once.

The study results show that proteins in the BET family have a strong influence on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. This indicates that the defined family of proteins govern many aspects of acute inflammatory diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, sepsis and cardiovascular disease, among others, and that they should be explored as a potential target to treat a wide variety of diseases.

"Our study suggests that it is not a coincidence that patients with diabetes experience higher risk of death from cancer, or that patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis and insulin resistance, also are more likely to be obese or suffer from inflammatory complications," said Belkina. "This requires us to think of diverse diseases of different organs as much more closely related than our current division of medical specialities allows."

Future research should explore how to successfully and safely target and inhibit these proteins in order to stop the inflammatory response associated with a variety of diseases.

###

Research included in this press release was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases under grant award R56 DK090455 (Principal Investigator: Denis). END

Mechanisms regulating inflammation associated with type 2 diabetes, cancer identified

2013-03-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Where you're treated matters' in terms of cancer survival

2013-03-01

SEATTLE – A study of older patients with advanced head and neck cancers has found that where they were treated significantly influenced their survival.

The study, led by researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and published in the March 1 online edition of Cancer, found that patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a high number of head and neck cancers were 15 percent less likely to die of their disease as compared to patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a relatively low number of such cancers. The study also found that such patients ...

Illinois town provides a historical foundation for today's bee research

2013-03-01

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A study published in the journal Science reveals a decline in bee species since the late 1800s in West Central Illinois. The study could not have been conducted without the work of a 19th-century naturalist, says a co-author of the new research.

Charles Robertson, a self-taught entomologist who studied zoology and botany at Harvard University and the University of Illinois, was one of the first scientists to make detailed records of the interactions of wild bees and the plants they pollinate, says John Marlin, a co-author of the new analysis in Science. ...

New chemical probe provides tool to investigate role of malignant brain tumor domains

2013-03-01

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – In an article published as the cover story of the March 2013 issue of Nature Chemical Biology, Lindsey James, PhD, research assistant professor in the lab of Stephen Frye, Fred Eshelman Distinguished Professor in the UNC School of Pharmacy and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, announced the discovery of a chemical probe that can be used to investigate the L3MBTL3 methyl-lysine reader domain. The probe, named UNC1215, will provide researchers with a powerful tool to investigate the function of malignant brain tumor (MBT) domain ...

Study confirms safety of colonoscopy

2013-03-01

Colon cancer develops slowly. Precancerous lesions usually need many years to turn into a dangerous carcinoma. They are well detectable in an endoscopic examination of the colon called colonoscopy and can be removed during the same examination. Therefore, regular screening can prevent colon cancer much better than other types of cancer. Since 2002, colonoscopy is part of the national statutory cancer screening program in Germany for all insured persons aged 55 or older.

However, only one fifth of those eligible actually make use of the screening program. The reasons ...

Towards more sustainable construction

2013-03-01

This press release is available in French.

Montreal, March 1, 2013 – Construction in Montreal is under a microscope. Now more than ever, municipal builders need to comply with long-term urban planning goals. The difficulties surrounding massive projects like the Turcot interchange lead Montrealers to wonder if construction in this city is headed in the right direction. New research from Concordia University gives us hope that this could soon be the case if sufficient effort is made.

A team of graduate students from Concordia's Department of Geography, Planning and Environment ...

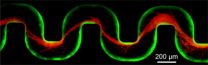

How do bacteria clog medical devices? Very quickly.

2013-03-01

A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National ...

New study could explain why some people get zits and others don't

2013-03-01

The bacteria that cause acne live on everyone's skin, yet one in five people is lucky enough to develop only an occasional pimple over a lifetime.

In a boon for teenagers everywhere, a UCLA study conducted with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute has discovered that acne bacteria contain "bad" strains associated with pimples and "good" strains that may protect the skin.

The findings, published in the Feb. 28 edition of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, could lead to a myriad of new therapies to ...

Where the wild things go… when there's nowhere else

2013-03-01

Ecologists have evidence that some endangered primates and large cats faced with relentless human encroachment will seek sanctuary in the sultry thickets of mangrove and peat swamp forests. These harsh coastal biomes are characterized by thick vegetation — particularly clusters of salt-loving mangrove trees — and poor soil in the form of highly acidic peat, which is the waterlogged remains of partially decomposed leaves and wood. As such, swamp forests are among the few areas in many African and Asian countries that humans are relatively less interested in exploiting (though ...

Thyroid hormones reduce damage and improve heart function after myocardial infarction in rats

2013-03-01

Thyroid hormone treatment administered to rats at the time of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) led to significant reduction in the loss of heart muscle cells and improvement in heart function, according to a study published by a team of researchers led by A. Martin Gerdes and Yue-Feng Chen from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The findings, published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, have bolstered the researchers' contention that thyroid hormones may help reduce heart damage in humans with cardiac diseases.

"I am extremely ...

Groundbreaking UK study shows key enzyme missing from aggressive form of breast cancer

2013-03-01

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 28, 2013) – A groundbreaking new study led by the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center's Dr. Peter Zhou found that triple-negative breast cancer cells are missing a key enzyme that other cancer cells contain — providing insight into potential therapeutic targets to treat the aggressive cancer. Zhou's study is unique in that his lab is the only one in the country to specifically study the metabolic process of triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Normally, all cells — including cancerous cells — use glucose to initiate the process of making Adenosine-5'-triphosphate ...