(Press-News.org) New research from the University of Toronto Scarborough shows that animal dispersal is influenced by a gene associated with feeding and food search behaviours.

The study, which was carried out by UTSC Professor Mark Fitzpatrick and PhD student Allan Edelsparre, provides one of the first aimed at gaining a functional understanding of how genes can influence dispersal tendencies in nature.

Using common fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), the researchers observed how two different foraging types – known as sitter flies and rover flies – moved over large distances when released in nature. They discovered that the rover flies, which are very active foragers as larvae, dispersed farther and more frequently than sitter flies, which are less active foragers.

"What is fascinating is that we were able to observe, both in nature and in the laboratory, a system that links their feeding activity as larvae and how far they disperse as adults to levels of the foraging gene in their brain," says Fitzpatrick.

In the laboratory, the researchers were also able to confirm that the foraging gene influences dispersal by artificially inducing higher levels of the gene in sitters, which caused them to disperse like rover flies.

Work on the dispersal tendencies of a variety of animals seem to converge on the notion that dispersal is not a random process.

"Some individuals seem to have greater innate dispersal tendencies than others," says Edelsparre. Like humans, animals have personalities including shyness, aggressiveness, and sociability. Individuals with similar personalities often share several related behaviours and the authors suggest this may explain the link between feeding, food searching, and dispersal.

The findings may also shine light on links between feeding and dispersal in other animals. For example, dispersing naked more rats and lizards are more active eaters. Fitzpatrick and Edelsparre also point to studies tracing the chemical signatures and dental records of early humans. While the chemical isotopes and tooth wear of most specimens indicated they foraged and resided locally, a few specimens carried isotopes from very different habitats suggesting they may have immigrated from far away. Whether the foraging gene plays a role in their dispersal tendencies remains unknown.

The ability to predict differences in dispersal tendencies could also influence how we build and maintain natural corridors for threatened species or how we stop the spread of invasive species like the round goby, emerald ash borer, or the Asian longhorned beetle, adds Fitzpatrick. "We are at an exciting critical juncture where work on genes and genomes are merging with a wealth of work on behavioural personalities and animal movement ecology," he says.

The research is currently available online and will be published in the upcoming edition of Ecology Letters.

INFORMATION:

Contact:

Dr. Mark Fitzpatrick

Assistant Professor

Integrative Behaviour and Neuroscience Group

Dept. of Biological Sciences at the University of Toronto Scarborough

416.208.2703 (office) or 416.208.2799 (lab)

Allan Edelsparre

PhD Student, University of Toronto Scarborough

a.edelsparre@utoronto.ca

Cell: 905-809-8581

New study shows a genetic link between feeding behavior and animal dispersal

2014-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ecotourism reduces poverty near protected parks, Georgia State University research shows

2014-02-24

ATLANTA--Protected natural areas in Costa Rica reduced poverty by 16 percent in neighboring communities, mainly by encouraging ecotourism, according to new research published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Although earlier studies indicated that establishing protected areas in poor regions can lead to reductions in poverty, there was no clear understanding why or how it happens.

"Our goal was to show exactly how environmental protection can reduce poverty in poorer nations rather than exacerbate it, as many people fear," says co-author ...

AGU: Uncovering the secret world of the Plastisphere

2014-02-24

HONOLULU – Scientists are revealing how microbes living on floating pieces of plastic marine debris affect the ocean ecosystem, and the potential harm they pose to invertebrates, humans and other animals. New research being presented here today delves deeper into the largely unexplored world of the "Plastisphere" – an ecological community of microbial organisms living on ocean plastic that was first discovered last year.

When scientists initially studied the Plastisphere, they found that at least 1,000 different types of microbes thrive on these tiny plastic islands, ...

Pinwheel 'living' crystals and the origin of life

2014-02-24

ANN ARBOR—Simply making nanoparticles spin coaxes them to arrange themselves into what University of Michigan researchers call 'living rotating crystals' that could serve as a nanopump. They may also, incidentally, shed light on the origin of life itself.

The researchers refer to the crystals as 'living' because they, in a sense, take on a life of their own from very simple rules.

Sharon Glotzer, the Stuart W. Churchill Collegiate Professor of Chemical Engineering, and her team found that when they spun individual nanoparticles in a simulation—some clockwise and some ...

New study supports body shape index as predictor of mortality

2014-02-24

In 2012, Dr. Nir Krakauer, an assistant professor of civil engineering in CCNY's Grove School of Engineering, and his father, Dr. Jesse Krakauer, MD, developed a new method to quantify the risk specifically associated with abdominal obesity.

A follow-up study, published February 20 by the online journal PLOS ONE, supports their contention that the technique, known as A Body Shape Index (ABSI), is a more effective predictor of mortality than Body Mass Index (BMI), the most common measure used to define obesity.

The team analyzed data for 7,011 adults, 18+, who participated ...

Volcanoes, including Mount Hood in the US, can quickly become active

2014-02-24

New research results suggest that magma sitting 4-5 kilometers beneath the surface of Oregon's Mount Hood has been stored in near-solid conditions for thousands of years.

The time it takes to liquefy and potentially erupt, however, is surprisingly short--perhaps as little as a couple of months.

The key to an eruption, geoscientists say, is to elevate the temperature of the rock to more than 750 degrees Celsius, which can happen when hot magma from deep within the Earth's crust rises to the surface.

It was the mixing of hot liquid lava with cooler solid magma that ...

Geosphere covers Mexico, the Colorado Plateau, Russia, and offshore New Jersey

2014-02-24

Boulder, Colo., USA – New Geosphere postings cover using traditional geochemistry with novel micro-analytical techniques to understand the western Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt; an investigation of mafic rock samples from a volcanic field near Yampa, Colorado, travertine deposits in the southeastern Colorado Plateau of New Mexico and Arizona; a study "Slushball Earth" rocks from Karelia, Russia, using field and micro-analytical techniques; and an addition to the "The History and Impact of Sea-level Change Offshore New Jersey" special issue.

Abstracts for these and other ...

Building artificial cells will be a noisy business

2014-02-24

Engineers like to make things that work. And if one wants to make something work using nanoscale components—the size of proteins, antibodies, and viruses—mimicking the behavior of cells is a good place to start since cells carry an enormous amount of information in a very tiny packet. As Erik Winfree, professor of computer science, computation and neutral systems, and bioengineering, explains, "I tend to think of cells as really small robots. Biology has programmed natural cells, but now engineers are starting to think about how we can program artificial cells. We want ...

Study evaluates role of infliximab in treating Kawasaki disease

2014-02-24

Kawasaki Disease (KD) is a severe childhood disease that many parents, even some doctors, mistake for an inconsequential viral infection. If not diagnosed or treated in time, it can lead to irreversible heart damage.

Signs of KD include prolonged fever associated with rash, red eyes, mouth, lips and tongue, and swollen hands and feet with peeling skin. The disease causes damage to the coronary arteries in a quarter of untreated children and may lead to serious heart problems in early adulthood. There is no diagnostic test for Kawasaki disease, and current treatment fails ...

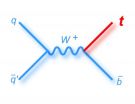

Scientists complete the top quark puzzle

2014-02-24

Scientists on the CDF and DZero experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory have announced that they have found the final predicted way of creating a top quark, completing a picture of this particle nearly 20 years in the making.

The two collaborations jointly announced on Friday, Feb. 21 that they had observed one of the rarest methods of producing the elementary particle – creating a single top quark through the weak nuclear force, in what is called the "s-channel." For this analysis, scientists from the CDF and DZero collaborations ...

As hubs for bees and pollinators, flowers may be crucial in disease transmission

2014-02-24

AMHERST, Mass. – Like a kindergarten or a busy airport where cold viruses and other germs circulate freely, flowers are common gathering places where pollinators such as bees and butterflies can pick up fungal, bacterial or viral infections that might be as benign as the sniffles or as debilitating as influenza.

But "almost nothing is known regarding how pathogens of pollinators are transmitted at flowers," postdoctoral researcher Scott McArt and Professor Lynn Adler at the University of Massachusetts Amherst write. "As major hubs of plant-animal interactions throughout ...