(Press-News.org) An unlit, deserted car park at night, footsteps in the gloom. The heart beats faster and the stomach ties itself in knots. We often feel threatening situations in our stomachs. While the brain has long been viewed as the centre of all emotions, researchers are increasingly trying to get to the bottom of this proverbial gut instinct.

It is not only the brain that controls processes in our abdominal cavity; our stomach also sends signals back to the brain. At the heart of this dialogue between the brain and abdomen is the vagus nerve, which transmits signals in both directions – from the brain to our internal organs (via the so called efferent nerves) and from the stomach back to our brain (via the afferent nerves). By cutting the afferent nerve fibres in rats, a team of scientists led by Urs Meyer, a researcher in the Group of ETH Zurich professor Wolfgang Langhans, turned this two-way communication into a one-way street, enabling the researchers to get to the bottom of the role played by gut instinct. In the test animals, the brain was still able to control processes in the abdomen, but no longer received any signals from the other direction.

Less fear without gut instinct

In the behavioural studies, the researchers determined that the rats were less wary of open spaces and bright lights compared with controlled rats with an intact vagus nerve. "The innate response to fear appears to be influenced significantly by signals sent from the stomach to the brain," says Meyer.

Nevertheless, the loss of their gut instinct did not make the rats completely fearless: the situation for learned fear behaviour looked different. In a conditioning experiment, the rats learned to link a neutral acoustic stimulus – a sound – to an unpleasant experience. Here, the signal path between the stomach and brain appeared to play no role, with the test animals learning the association as well as the control animals. If, however, the researchers switched from a negative to a neutral stimulus, the rats without gut instinct required significantly longer to associate the sound with the new, neutral situation. This also fits with the results of a recently published study conducted by other researchers, which found that stimulation of the vagus nerve facilitates relearning, says Meyer.

These findings are also of interest to the field of psychiatry, as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for example, is linked to the association of neutral stimuli with fear triggered by extreme experiences. Stimulation of the vagus nerve could help people with PTSD to once more associate the triggering stimuli with neutral experiences. Vagus nerve stimulation is already used today to treat epilepsy and, in some cases, depression.

Stomach influences signalling in the brain

"A lower level of innate fear, but a longer retention of learned fear – this may sound contradictory," says Meyer. However, innate and conditioned fear are two different behavioural domains in which different signalling systems in the brain are involved. On closer investigation of the rats' brains, the researchers found that the loss of signals from the abdomen changes the production of certain signalling substances, so called neurotransmitters, in the brain.

"We were able to show for the first time that the selective interruption of the signal path from the stomach to the brain changed complex behavioural patterns. This has traditionally been attributed to the brain alone," says Meyer. The study shows clearly that the stomach also has a say in how we respond to fear; however, what it says, i.e. precisely what it signals, is not yet clear. The researchers hope, however, that they will be able to further clarify the role of the vagus nerve and the dialogue between brain and body in future studies.

INFORMATION:

Further reading:

Klarer M, Arnold M, Günther L, Winter C, Langhans W, Meyer U: Gut Vagal Afferents Differentially Modulate Innate Anxiety and Learned Fear. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21 May 2014. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0252-14.2014

How the gut feeling shapes fear

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Radiofrequency ablation and complete endoscopic resection equally effective for dysplastic Barrett's esophagus

2014-05-22

DOWNERS GROVE, Ill. – May 21, 2014 – According to a new systematic review article, radiofrequency ablation and complete endoscopic resection are equally effective in the short-term treatment of dysplastic Barrett's esophagus, but adverse event rates are higher with complete endoscopic resection. The article comparing the two treatments appears in the May issue of GIE: Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

Barrett's esophagus is a condition in which the lining of the esophagus ...

Molecule acts as umpire to make tough life-or-death calls

2014-05-22

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – May 20, 2014) Researchers have demonstrated that an enzyme required for animal survival after birth functions like an umpire, making the tough calls required for a balanced response to signals that determine if cells live or die. St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists led the study, which was published online and appears in the May 22 edition of the scientific journal Cell.

The work involved the enzyme receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1). While RIPK1 is known to be involved in many vital cell processes, this study shows that its pivotal ...

Aggressive behavior observed after alcohol-related priming

2014-05-22

May 22, 2014-- Researchers from California State University, Long Beach, the University of Kent and the University of Missouri collaborated on a study to test whether briefly exposing participants to alcohol-related terms increases aggressive behavior. It has been well documented by previous research that the consumption of alcohol is directly linked to an increase in aggression and other behavioral extremes. But can simply seeing alcohol-related words have a similar effect on aggressive behavior?

Designing the experiment

The study, published in the journal Personality ...

First broadband wireless connection ... to the moon?!

2014-05-22

WASHINGTON, May 22, 2014—If future generations were to live and work on the moon or on a distant asteroid, they would probably want a broadband connection to communicate with home bases back on Earth. They may even want to watch their favorite Earth-based TV show. That may now be possible thanks to a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory who, working with NASA last fall, demonstrated for the first time that a data communication technology exists that can provide space dwellers with the connectivity we all enjoy here ...

On quantification of the growth of compressible mixing layer

2014-05-22

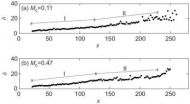

CML has been a research topic for more than five decades, due to its wide applications in propulsion design. Mixing in CML is controlled by the compressibility effects of velocity and density variations over the mixing layer, and quantified by the growth rate of CML. However, the lack of understanding of various definitions of mixing thicknesses has yielded scatter in analyzing experimental data. Prof. SHE ZhenSu and his colleagues at the State Key Laboratory for Turbulence and Complex Systems, Peking University investigated the growth of compressible mixing layer by introducing ...

Nanoshell-emitters hybrid nanoobject was proposed as promising 2-photon fluorescence probe

2014-05-22

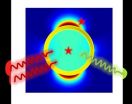

Two-photon excitation fluorescence is growing in popularity in the bioimaging field but is limited by fluorophores' extremely low two-photon absorption cross-section. The researcher Dr. Guowei Lu and co-workers from State Key Laboratory for Mesoscopic Physics, Department of Physics, Peking University, are endeavoring to develop efficient fluorescent probes with improved two-photon fluorescence (TPF) performance. They theoretically present a promising bright probe using gold nanoshell to improve the TPF performances of fluorescent emitters. Their work, entitled "Plasmonic-Enhanced ...

Stanford research shows importance of European farmers adapting to climate change

2014-05-22

A new Stanford study finds that due to an average 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit of warming expected by 2040, yields of wheat and barley across Europe will drop more than 20 percent.

New Stanford research reveals that farmers in Europe will see crop yields affected as global temperatures rise, but that adaptation can help slow the decline for some crops.

For corn, the anticipated loss is roughly 10 percent, the research shows. Farmers of these crops have already seen yield growth slow down since 1980 as temperatures have risen, though other policy and economic factors have ...

Symbiosis or capitalism? A new view of forest fungi

2014-05-22

The so-called symbiotic relationship between trees and the fungus that grow on their roots may actually work more like a capitalist market relationship between buyers and sellers, according to the new study published in the journal New Phytologist.

Recent experiments in the forests of Sweden had brought into a question a long-held theory of biology: that the fungi or mycorrhizae that grow on tree roots work with trees in a symbiotic relationship that is beneficial for both the fungi and the trees, providing needed nutrients to both parties. These fungi, including many ...

Stanford, MIT scientists find new way to harness waste heat

2014-05-22

Vast amounts of excess heat are generated by industrial processes and by electric power plants. Researchers around the world have spent decades seeking ways to harness some of this wasted energy. Most such efforts have focused on thermoelectric devices – solid-state materials that can produce electricity from a temperature gradient – but the efficiency of such devices is limited by the availability of materials.

Now researchers at Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found a new alternative for low-temperature waste-heat conversion into ...

A new target for alcoholism treatment: Kappa opioid receptors

2014-05-22

Philadelphia, PA, May 22, 2014 – The list of brain receptor targets for opiates reads like a fraternity: Mu Delta Kappa. The mu opioid receptor is the primary target for morphine and endogenous opioids like endorphin, whereas the delta opioid receptor shows the highest affinity for endogenous enkephalins. The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) is very interesting, but the least understood of the opiate receptor family.

Until now, the mu opioid receptor received the most attention in alcoholism research. Naltrexone, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for ...