(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

New Danish genetics research explains the high incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Greenlandic population. The ground-breaking findings have just been published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature....

Click here for more information.

A spectacular piece of detective work has mapped a special gene variant among Greenlanders which plays a particularly important role in the development of type 2 diabetes. The results have been published in Nature and can be used to improve prevention and treatment options for those genetically at-risk.

In collaboration with Greenland researchers from Steno Diabetes Center and University of Southern Denmark, researchers from the University of Copenhagen have carried out the ground-breaking genetic analysis based on blood samples from 5,000 people or approx. 10% of the modestly-sized population inhabiting an area larger than western Europe.

– We have found a gene variant in the population of Greenland which markedly increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The gene variant is only found in Greenlanders and explains 15% of cases of diabetes in the country, explains Professor Torben Hansen from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen who conducts research into the link between our genetic make-up and the development of diabetes and obesity as well as the effect of treatment. Together with Associate Professor Anders Albrechtsen from the Bioinformatics Centre at the University of Copenhagen, he is the driving force behind the findings.

The study was a challenge in several ways. Collecting samples from 10% of the population of such a big country was a huge logistical task, and it was only possible because so many Greenlanders volunteered to participate. Additionally, the study was a statistical challenge as many of the participants are of both Inuit and European ancestry – and because many of the participants are related:

– For some of the analyses, we therefore had to develop new methods, and for others, we used methods which were only developed recently, explains postdoc Ida Moltke from the Department of Human Genetics at the University of Chicago. She is one of the two first authors of the article and responsible for the statistical analyses.

Potent gene variant

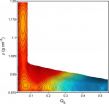

By means of advanced gene chip technology – which over the past ten years has led to a marked increase in the speed of genetic analyses – the Danish team analysed the 5,000 blood samples for 250,000 gene variants which play a role in metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease.

– Our attention was quite soon caught by a particular variant of the TBC1D4 gene which controls glucose uptake in muscle cells. Roughly speaking, this means that in carriers of this particular gene variant, the uptake of glucose by the muscles is hampered, for example after a meal which results in raised blood glucose levels. However, this particular gene variant is primarily found in Greenlanders, and about 23% of the Greenlandic population are carriers of the variant which prevents the optimum functioning of the glucose transporters in the cells. The gene variant is not found in Europeans at all, explains Assistant Professor Niels Grarup from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen, the other first author of the article.

Sixty per cent of the test individuals aged 40+ who have inherited the gene variant from both their mother and their father have type 2 diabetes. For the 60+ group, the figure is 80%:

– If you have inherited the gene variant from both your parents, the risk of developing diabetes is, of course, extremely high. This was the case for 4% of the Greenlanders we examined. We already know of a number of gene variants in European populations which slightly raise the risk of developing diabetes, but this new gene variant has a much more pronounced effect than we have ever seen before, says Niels Grarup.

From seal meat to too many sweets

From a scientific point of view, looking at relatively isolated communities makes a lot of sense when you are conducting research into pathological genes. Particular biological mechanisms are much more easily identified in isolated populations, such as the people of Greenland.

– Several epidemiological studies have looked at the health implications of the transition from life as sealers and hunters in small isolated communities to a modern lifestyle with appreciable dietary changes. Perhaps the gene variant which has been identified can be interpreted as a sign of natural selection as the traditional Greenlandic diet consisted primarily of protein and fat from sea animals, i.e. an extremely low-carb diet. However, so far these are but speculations, says Associate Professor Anders Albrechtsen.

The data will be studied further in the coming years. For example, Professor Marit Jørgensen from the Steno Diabetes Center and Professor Peter Bjerregaard from the National Institute of Public Health will continue the epidemiological studies, among other things to establish the risk of cardiovascular disease among carriers of the special gene variant.

INFORMATION:

Contact:

Torben Hansen

Mobil: +45 20 56 53 01

Scientists break the genetic code for diabetes in Greenland

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Familiar yet strange: Water's 'split personality' revealed by computer model

2014-06-18

Seemingly ordinary, water has quite puzzling behavior. Why, for example, does ice float when most liquids crystallize into dense solids that sink?

Using a computer model to explore water as it freezes, a team at Princeton University has found that water's weird behaviors may arise from a sort of split personality: at very cold temperatures and above a certain pressure, water may spontaneously split into two liquid forms.

The team's findings were reported in the journal Nature.

"Our results suggest that at low enough temperatures water can coexist as two different ...

Collecting light with artificial moth eyes

2014-06-18

Rust – iron oxide – could revolutionise solar cell technology. This usually unwanted substance can be used to make photoelectrodes which split water and generate hydrogen. Sunlight is thereby directly converted into valuable fuel rather than first being used to generate electricity. Unfortunately, as a raw material iron oxide has its limitations. Although it is unbelievably cheap and absorbs light in exactly the wavelength region where the sun emits the most energy, it conducts electricity very poorly and must therefore be used in the form of an extremely thin film in ...

Breathalyzer test may detect deadliest cancer

2014-06-18

Lung cancer causes more deaths in the U.S. than the next three most common cancers combined (colon, breast, and pancreatic). The reason for the striking mortality rate is simple: poor detection. Lung cancer attacks without leaving any fingerprints, quietly afflicting its victims and metastasizing uncontrollably – to the point of no return.

Now a new device developed by a team of Israeli, American, and British cancer researchers may turn the tide by both accurately detecting lung cancer and identifying its stage of progression. The breathalyzer test, embedded with a "NaNose" ...

Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growth

2014-06-18

LA JOLLA, CA—June 18, 2014 —Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a crucial process that regulates the development of blood vessels. The finding could lead to new treatments for disorders involving abnormal blood vessel growth, including common disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and cancer.

"Essentially we've shown how the protein SerRS acts as a brake on new blood vessel growth and pairs with the growth-promoting transcription factor c-Myc to bring about proper vascular development," said TSRI Professor Xiang-Lei Yang. "They act as the ...

Inflammation in fat tissue helps prevent metabolic disease

2014-06-18

DALLAS – June 18, 2014 – Chronic tissue inflammation is typically associated with obesity and metabolic disease, but new research from UT Southwestern Medical Center now finds that a level of "healthy" inflammation is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, such as fatty liver.

"There is such a thing as 'healthy' inflammation, meaning inflammation that allows the tissue to grow and has overall benefits to the tissue itself and the whole body," said Dr. Philipp Scherer, Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research and Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell ...

Unlocking the therapeutic potential of SLC13 transporters

2014-06-18

Researchers have provided the first functional analysis of a member of a family of transporter proteins implicated in diabetes, obesity, and lifespan. The study appears in the June issue of The Journal of General Physiology.

Members of the SLC13 transporter family play a key role in the regulation of fat storage, insulin resistance, and other processes. Some SLC13 transporters mediate the transport of Krebs cycle intermediates—compounds essential for the body's metabolic activity—across the cell membrane. Previous studies have shown that loss of one member of this family ...

Penn team links placental marker of prenatal stress to brain mitochondrial dysfunction

2014-06-18

When a woman experiences a stressful event early in pregnancy, the risk of her child developing autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia increases. Yet how maternal stress is transmitted to the brain of the developing fetus, leading to these problems in neurodevelopment, is poorly understood.

New findings by University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine scientists suggest that an enzyme found in the placenta is likely playing an important role. This enzyme, O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine transferase, or OGT, translates maternal stress into a reprogramming ...

Study examines how brain 'reboots' itself to consciousness after anesthesia

2014-06-18

One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint how genetic mutation causes early brain damage

2014-06-18

JUPITER, FL, June 18, 2014 – Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shed light on how a specific kind of genetic mutation can cause damage during early brain development that results in lifelong learning and behavioral disabilities. The work suggests new possibilities for therapeutic intervention.

The study, which focuses on the role of a gene known as Syngap1, was published June 18, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Neuron. In humans, mutations in Syngap1 are known to cause devastating forms of intellectual disability ...

Blocking brain's 'internal marijuana' may trigger early Alzheimer's deficits, study shows

2014-06-18

A new study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine has implicated the blocking of endocannabinoids — signaling substances that are the brain's internal versions of the psychoactive chemicals in marijuana and hashish — in the early pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

A substance called A-beta — strongly suspected to play a key role in Alzheimer's because it's the chief constituent of the hallmark clumps dotting the brains of people with Alzheimer's — may, in the disease's earliest stages, impair learning and memory by blocking the natural, beneficial ...