(Press-News.org) During evolutionary diversification of vertebrate limbs, the number of toes in even-toed ungulates such as cattle and pigs was reduced and transformed into paired hooves. Scientists at the University of Basel have identified a gene regulatory switch that was key to evolutionary adaption of limbs in ungulates. The study provides fascinating insights into the molecular history of evolution and is published by Nature today.

The fossil record shows that the first primitive even-toed ungulates had legs with five toes (=digits), just like modern mice and humans. During their evolution, the basic limb skeletal structure was significantly modified such that today's hippopotami have four toes, while the second and fifth toe face backwards in pigs. In cattle, the distal skeleton consists of two rudimentary dew claws and two symmetrical and elongated middle digits that form the cloven hoof, which provides good traction for walking and running on different terrains.

Comparative analysis of embryonic development

A team led by Prof. Rolf Zeller from the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel has now investigated the molecular changes which could be responsible for the evolutionary adaptation of ungulate limbs. To this aim, they compared the activity of genes in mouse and cattle embryos which control the development of fingers and toes during embryonic development.

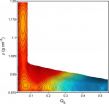

The development of limbs in both species is initially strikingly similar and molecular differences only become apparent during hand and foot plate development: in mouse embryos the so-called Hox gene transcription factors are distributed asymmetrically in the limb buds which is crucial to the correct patterning of the distal skeleton. In contrast, their distribution becomes symmetrical from early stages onward in limb buds of cattle embryos: "We think this early loss of molecular asymmetry triggered the evolutionary changes that ultimately resulted in development of cloven-hoofed distal limb skeleton in cattle and other even-toed ungulates", says Developmental Geneticist Prof. Rolf Zeller.

Loss of asymmetry preceded the reduction and loss of digits

The scientists in the Department of Biomedicine then focused their attention on the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway, as it controls Hox gene expression and the development of five fingers and toes in mice and humans. They discovered that the gene expression in limb buds of cattle embryos is altered, such that the cells giving rise to the distal skeleton fail to express the Hedgehog receptor, called Patched1. Normally, this receptor serves as an antenna for SHH, but without Patched1 the SHH signal cannot be received and the development of five distinct digits is disrupted. The researchers could establish that the altered genomic region – a so-called cis-regulatory module – is linked to the observed loss of Patched1 receptors and digit asymmetry in cattle embryos.

"The identified genetic alterations affecting this regulatory switch offer unprecedented molecular insights into how the limbs of even-toed ungulates diverged from those of other mammals roughly 55 million years ago", explains Rolf Zeller. At this stage, it is unclear what triggered inactivation of the Patched1 gene regulatory switch. "We assume that it is the result of progressive evolution, as this switch degenerated in cattle and other even-toed ungulates, while it remained fully functional in some vertebrates such as mice and humans".

INFORMATION:

Original source

Javier Lopez-Rios, Amandine Duchesne, Dario Speziale, Guillaume Andrey, Kevin A. Peterson, Philipp Germann, Erkan Ünal, Jing Liu, Sandrine Floriot, Sarah Barbey, Yves Gallard, Magdalena Müller-Gerbl, Andrew D. Courtney, Christophe Klopp, Sabrina Rodriguez, Robert Ivanek, Christian Beisel, Carol Wicking, Dagmar Iber, Benoit Robert, Andrew P. McMahon, Denis Duboule and Rolf Zeller

Attenuated sensing of SHH by Ptch1 underlies evolution of bovine limbs

Nature (2014) | doi: 10.1038/nature13289

Evolutionary biology: Why cattle only have 2 toes

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists break the genetic code for diabetes in Greenland

2014-06-18

VIDEO:

New Danish genetics research explains the high incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Greenlandic population. The ground-breaking findings have just been published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature....

Click here for more information.

A spectacular piece of detective work has mapped a special gene variant among Greenlanders which plays a particularly important role in the development of type 2 diabetes. The results have been published in Nature and can be ...

Familiar yet strange: Water's 'split personality' revealed by computer model

2014-06-18

Seemingly ordinary, water has quite puzzling behavior. Why, for example, does ice float when most liquids crystallize into dense solids that sink?

Using a computer model to explore water as it freezes, a team at Princeton University has found that water's weird behaviors may arise from a sort of split personality: at very cold temperatures and above a certain pressure, water may spontaneously split into two liquid forms.

The team's findings were reported in the journal Nature.

"Our results suggest that at low enough temperatures water can coexist as two different ...

Collecting light with artificial moth eyes

2014-06-18

Rust – iron oxide – could revolutionise solar cell technology. This usually unwanted substance can be used to make photoelectrodes which split water and generate hydrogen. Sunlight is thereby directly converted into valuable fuel rather than first being used to generate electricity. Unfortunately, as a raw material iron oxide has its limitations. Although it is unbelievably cheap and absorbs light in exactly the wavelength region where the sun emits the most energy, it conducts electricity very poorly and must therefore be used in the form of an extremely thin film in ...

Breathalyzer test may detect deadliest cancer

2014-06-18

Lung cancer causes more deaths in the U.S. than the next three most common cancers combined (colon, breast, and pancreatic). The reason for the striking mortality rate is simple: poor detection. Lung cancer attacks without leaving any fingerprints, quietly afflicting its victims and metastasizing uncontrollably – to the point of no return.

Now a new device developed by a team of Israeli, American, and British cancer researchers may turn the tide by both accurately detecting lung cancer and identifying its stage of progression. The breathalyzer test, embedded with a "NaNose" ...

Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growth

2014-06-18

LA JOLLA, CA—June 18, 2014 —Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a crucial process that regulates the development of blood vessels. The finding could lead to new treatments for disorders involving abnormal blood vessel growth, including common disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and cancer.

"Essentially we've shown how the protein SerRS acts as a brake on new blood vessel growth and pairs with the growth-promoting transcription factor c-Myc to bring about proper vascular development," said TSRI Professor Xiang-Lei Yang. "They act as the ...

Inflammation in fat tissue helps prevent metabolic disease

2014-06-18

DALLAS – June 18, 2014 – Chronic tissue inflammation is typically associated with obesity and metabolic disease, but new research from UT Southwestern Medical Center now finds that a level of "healthy" inflammation is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, such as fatty liver.

"There is such a thing as 'healthy' inflammation, meaning inflammation that allows the tissue to grow and has overall benefits to the tissue itself and the whole body," said Dr. Philipp Scherer, Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research and Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell ...

Unlocking the therapeutic potential of SLC13 transporters

2014-06-18

Researchers have provided the first functional analysis of a member of a family of transporter proteins implicated in diabetes, obesity, and lifespan. The study appears in the June issue of The Journal of General Physiology.

Members of the SLC13 transporter family play a key role in the regulation of fat storage, insulin resistance, and other processes. Some SLC13 transporters mediate the transport of Krebs cycle intermediates—compounds essential for the body's metabolic activity—across the cell membrane. Previous studies have shown that loss of one member of this family ...

Penn team links placental marker of prenatal stress to brain mitochondrial dysfunction

2014-06-18

When a woman experiences a stressful event early in pregnancy, the risk of her child developing autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia increases. Yet how maternal stress is transmitted to the brain of the developing fetus, leading to these problems in neurodevelopment, is poorly understood.

New findings by University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine scientists suggest that an enzyme found in the placenta is likely playing an important role. This enzyme, O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine transferase, or OGT, translates maternal stress into a reprogramming ...

Study examines how brain 'reboots' itself to consciousness after anesthesia

2014-06-18

One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint how genetic mutation causes early brain damage

2014-06-18

JUPITER, FL, June 18, 2014 – Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shed light on how a specific kind of genetic mutation can cause damage during early brain development that results in lifelong learning and behavioral disabilities. The work suggests new possibilities for therapeutic intervention.

The study, which focuses on the role of a gene known as Syngap1, was published June 18, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Neuron. In humans, mutations in Syngap1 are known to cause devastating forms of intellectual disability ...