(Press-News.org) Scientists at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have made the first structural observations of liquid water at temperatures down to minus 51 degrees Fahrenheit, within an elusive "no-man's land" where water's strange properties are super-amplified.

The research, made possible by SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser and reported June 18 in Nature, opens a new window for exploring liquid water in these exotic conditions, and promises to improve our understanding of its unique properties at the more natural temperatures and states that are relevant to global ocean currents, climate and biology.

Scientists have known for some time that water can remain liquid at extremely cold temperatures, but they've never before been able to examine its molecular structure in this zone.

"Water is not only essential for life as we know it, but it also has very strange properties compared to most other liquids," said Anders Nilsson, deputy director of the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, a joint SLAC/Stanford institute, and leader of the research. "Now, thanks to LCLS, we have finally been able to enter this cold zone that should provide new information about the unique nature of water."

Not Your Typical Liquid

Despite its simple molecular structure, water has many weird traits: Its solid form is less dense than its liquid form, which is why ice floats; it can absorb a large amount of heat, which is carried long distances by ocean currents and has a profound impact on climate; and its peculiar density profile prevents oceans and lakes from freezing solid all the way to the bottom, allowing fish to survive the winter.

These traits are amplified when purified water is supercooled. When water is very pure, with nothing to seed the formation of ice crystals, it can remain liquid at much lower temperatures than normal. The temperature range of water from about minus 42 to minus 172 degrees has been dubbed no-man's land. For decades scientists have sought to better explore what happens to water molecules at temperatures below minus 42 degrees, but they had to rely largely on theory and modeling.

Femtosecond Shutter Speeds

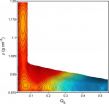

Now the LCLS, with X-ray laser pulses just quadrillionths of a second long, allows researchers to capture rapid-fire snapshots showing the detailed molecular structure of water in this mysterious zone the instant before it freezes. The research showed that water's molecular structure transforms continuously as it enters this realm, and with further cooling the structural changes accelerate more dramatically than theoretical models had predicted.

For this experiment, researchers produced a steady flow of tiny water droplets in a vacuum chamber. As the drops traveled toward the laser beam, some of their liquid rapidly evaporated, supercooling the remaining liquid. (The same process cools us when we sweat.) By adjusting the distance the droplets traveled, the researchers were able to fine-tune the temperatures they reached on arrival at the X-ray laser beam.

Colder Still

Nilsson's team hopes to dive to even colder temperatures where water morphs into a glassy, non-crystalline solid. They also want to determine whether supercooled water reaches a critical point where its unusual properties peak, and to pinpoint the temperature at which this occurs.

"Our dream is to follow these dynamics as far as we can," Nilsson said. "Eventually our understanding of what's happening here in no-man's land will help us fundamentally understand water in all conditions."

INFORMATION:

Scientists at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and Stanford PULSE Institute; Stockholm University; Germany's DESY laboratory; the Helmholtz Center for Materials and Energy in Germany; and Stony Brook University in New York also contributed to the research. The work was partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, the SLAC Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program and the Swedish Research Council.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit http://www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC's LCLS is the world's most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation: J. A. Sellberg et al., Nature, 19 June 2014 (10.1038/nature13266)

Scientists take first dip into water's mysterious 'no-man's land'

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UEA researchers discover Achilles' heel in antibiotic-resistant bacteria

2014-06-18

Scientists at the University of East Anglia have made a breakthrough in the race to solve antibiotic resistance.

New research published today in the journal Nature reveals an Achilles' heel in the defensive barrier which surrounds drug-resistant bacterial cells.

The findings pave the way for a new wave of drugs that kill superbugs by bringing down their defensive walls rather than attacking the bacteria itself. It means that in future, bacteria may not develop drug-resistance at all.

The discovery doesn't come a moment too soon. The World Health Organization has warned ...

Identifying opposite patterns of climate change between the middle latitude areas

2014-06-18

Korean research team revealed conflicting climate change patterns between the middle latitude areas of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres in relation to glacial and interglacial cycles which have been puzzled for the past 60 years.

Doctor Kyoung-nam Jo from the Quaternary Geology Department of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources(KIGAM) revealed a clue for solving the riddle of past global climate change in his paper titled 'Mid-latitudinal interhemispheric hydrologic seesaw over the past 550,000 years' which was featured in the journal Nature.

This ...

Evolutionary biology: Why cattle only have 2 toes

2014-06-18

During evolutionary diversification of vertebrate limbs, the number of toes in even-toed ungulates such as cattle and pigs was reduced and transformed into paired hooves. Scientists at the University of Basel have identified a gene regulatory switch that was key to evolutionary adaption of limbs in ungulates. The study provides fascinating insights into the molecular history of evolution and is published by Nature today.

The fossil record shows that the first primitive even-toed ungulates had legs with five toes (=digits), just like modern mice and humans. During their ...

Scientists break the genetic code for diabetes in Greenland

2014-06-18

VIDEO:

New Danish genetics research explains the high incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Greenlandic population. The ground-breaking findings have just been published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature....

Click here for more information.

A spectacular piece of detective work has mapped a special gene variant among Greenlanders which plays a particularly important role in the development of type 2 diabetes. The results have been published in Nature and can be ...

Familiar yet strange: Water's 'split personality' revealed by computer model

2014-06-18

Seemingly ordinary, water has quite puzzling behavior. Why, for example, does ice float when most liquids crystallize into dense solids that sink?

Using a computer model to explore water as it freezes, a team at Princeton University has found that water's weird behaviors may arise from a sort of split personality: at very cold temperatures and above a certain pressure, water may spontaneously split into two liquid forms.

The team's findings were reported in the journal Nature.

"Our results suggest that at low enough temperatures water can coexist as two different ...

Collecting light with artificial moth eyes

2014-06-18

Rust – iron oxide – could revolutionise solar cell technology. This usually unwanted substance can be used to make photoelectrodes which split water and generate hydrogen. Sunlight is thereby directly converted into valuable fuel rather than first being used to generate electricity. Unfortunately, as a raw material iron oxide has its limitations. Although it is unbelievably cheap and absorbs light in exactly the wavelength region where the sun emits the most energy, it conducts electricity very poorly and must therefore be used in the form of an extremely thin film in ...

Breathalyzer test may detect deadliest cancer

2014-06-18

Lung cancer causes more deaths in the U.S. than the next three most common cancers combined (colon, breast, and pancreatic). The reason for the striking mortality rate is simple: poor detection. Lung cancer attacks without leaving any fingerprints, quietly afflicting its victims and metastasizing uncontrollably – to the point of no return.

Now a new device developed by a team of Israeli, American, and British cancer researchers may turn the tide by both accurately detecting lung cancer and identifying its stage of progression. The breathalyzer test, embedded with a "NaNose" ...

Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growth

2014-06-18

LA JOLLA, CA—June 18, 2014 —Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a crucial process that regulates the development of blood vessels. The finding could lead to new treatments for disorders involving abnormal blood vessel growth, including common disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and cancer.

"Essentially we've shown how the protein SerRS acts as a brake on new blood vessel growth and pairs with the growth-promoting transcription factor c-Myc to bring about proper vascular development," said TSRI Professor Xiang-Lei Yang. "They act as the ...

Inflammation in fat tissue helps prevent metabolic disease

2014-06-18

DALLAS – June 18, 2014 – Chronic tissue inflammation is typically associated with obesity and metabolic disease, but new research from UT Southwestern Medical Center now finds that a level of "healthy" inflammation is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, such as fatty liver.

"There is such a thing as 'healthy' inflammation, meaning inflammation that allows the tissue to grow and has overall benefits to the tissue itself and the whole body," said Dr. Philipp Scherer, Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research and Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell ...

Unlocking the therapeutic potential of SLC13 transporters

2014-06-18

Researchers have provided the first functional analysis of a member of a family of transporter proteins implicated in diabetes, obesity, and lifespan. The study appears in the June issue of The Journal of General Physiology.

Members of the SLC13 transporter family play a key role in the regulation of fat storage, insulin resistance, and other processes. Some SLC13 transporters mediate the transport of Krebs cycle intermediates—compounds essential for the body's metabolic activity—across the cell membrane. Previous studies have shown that loss of one member of this family ...