(Press-News.org) Because the severe autism-like condition Christianson Syndrome was only first reported in 1999 and some symptoms take more than a decade to appear, families and doctors urgently need fundamental information about it. A new study that doubles the number of cases now documented in the scientific literature provides the most definitive characterization of CS to date. The authors therefore propose the first diagnostic criteria for the condition.

"We're hoping that clinicians will use these criteria and that there will be more awareness among clinicians and the community about Christianson Syndrome," said Brown University biology and psychiatry Assistant Professor Dr. Eric Morrow, senior author of the study in press in the Annals of Neurology. "We're also hoping this study will impart an opportunity for families to predict what to expect for their child and what's a part of the syndrome."

In conducting their study, which includes detailed behavioral, medical and genetic observations of 14 boys with CS from 12 families, the team of scientists and physicians worked closely with families of the small but fast-growing Christianson Syndrome Association , including hosting the group's inaugural conference at Brown's Alpert Medical School last summer.

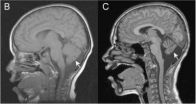

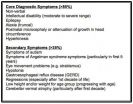

In their study, Morrow's team was able to quantify the most frequent symptoms specific to CS. These include moderate to severe intellectual disability, epilepsy, difficulty or inability walking and talking, attenuated head and brain growth, and hyperactivity. Boys sometimes exhibit other specific symptoms – including autism-like behaviors, low height and weight, acid reflux, and regressions in speech and motor skills after age 10 – that the researchers include as secondary proposed diagnostic criteria. A third of the boys also had potentially neurodegenerative problems such as atrophy of the cerebellum.

What's still not clear is whether the disease limits the eventual lifespan of patients.

Distinct genetic cause

Many CS traits, including a very happy disposition, appear similar to those of another autism-like condition, Angelman Syndrome, but the study defines important differences.

Among the most important ones is that the two syndromes have distinct genetic underpinnings. In all CS cases, said Morrow who treats autism patients at the E. P. Bradley Hospital in East Providence, boys have a mutation on the SLC9A6 gene on the X chromosome that disables production of a protein called NHE6 that is important for neurological development.

Girls, who have two X chromosomes, can also be carriers of CS mutations, but they appear to be affected differently and less severely or not at all, the study reports.

The connection to the SLC9A6 gene was first discovered in 2008. In analyzing the genomes of each patient and their parents in the new study, lead authors Matthew Pescosolido, a graduate student, and David Stein, a former undergraduate, found that each boy had only one mutation, but there were many different ones across the entire group. More often than not, they determined, the mutation was not inherited, but an unlucky "de novo" change that occurred in the affected boy. In two situations, boys in unrelated families happened to share the same mutation. These recurrent mutations suggest that there may be hotspots in the DNA for mutation at these sites, Morrow said, although further research will be necessary to sort this out.

Morrow said there is evidence that SLC9A6 mutations – and therefore CS – may be a relatively common source of X-linked intellectual disability. One study, for example found that SLC9A6 mutations in two of 200 people suspected of having X-linked ID. Another found that 1 in 19 families with a case of ID exhibited a mutation that truncated the NHE6 protein.

"If we assume that between 1-3 percent of the world's population is diagnosed with an intellectual disability and approximately 10-20 percent of the causes are due to X-linked genes, then we can estimate that CS may affect between 1 in 16,000 to 100,000 people," Morrow and his co-authors wrote. Worldwide that frequency would add up to more than 70,000 cases.

Relevance to autism, epilepsy

In a paper published last year, Morrow's research group found that NHE6 is underexpressed in the brains of many children with more general forms of autism. This potential connection suggests that learning about CS can help doctors and scientists learn about autism.

Similarly by studying the regression of walking and verbal skills among Christianson boys, Morrow said researchers could learn more about regressions in autism.

"Christianson syndrome, I hope will be a model," Morrow said. "If we could understand the biological mechanism that leads to that loss, and we can prevent it, by developing a treatment, then these kids will remain further ahead."

Such advances will require much more study, but Morrow said that by uncovering a variety of mutations that all lead to the disease, the study provides a wealth of new information for that work.

"We can now study these different mutations and learn how this protein works by how it gets inactivated," he said. "All the different ways it gets inactivated can actually inform us about the different components of the protein that have an important function."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Pescosolido, Stein and Morrow, other authors on the paper are Michael Schmidt, Dr. Christelle Moufawad El Achkar, Mark Sabbagh (another former Brown undergraduate), Dr. Jeffrey Rogg, Umadevi Tantravahi, Rebecca McLean, Dr. Judy Liu, and Annapurna Poduri.

This work was supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation (239834), the Nancy Lurie Marks Foundation and the newly formed Christianson Syndrome Association.

Diagnostic criteria for Christianson Syndrome

2014-07-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Nearsightedness increases with level of education and longer schooling

2014-07-21

Education and behavior have a greater impact on the development of nearsightedness than do genetic factors: With each school year completed, a person becomes more nearsighted. The higher the level of education completed, the more severe is the impairment of vision. These are the conclusions drawn by researchers at the Department of Ophthalmology at the Mainz University Medical Center from the results of the first population-based cohort study of this condition. A nearsighted eye is one in which the eyeball is too long in relation to the refractive power of the cornea and ...

Heart disease: First Canadian survey shows women unaware of symptoms and risk factors

2014-07-21

OTTAWA, July 21, 2014 – A new survey, ordered by the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, shows that a majority of Canadian women lack knowledge of heart disease symptoms and risk factors, and that a significant proportion is even unaware of their own risk status. The findings underscore the opportunity for patient education and intervention regarding risk and prevention of heart disease.

Heart disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in men and women. Our understanding of heart disease stems chiefly from clinical trials on men, but key features of the disease ...

Circumcision does not promote risky behavior by African men

2014-07-21

Men do not engage in riskier behaviors after they are circumcised, according to a study in Kenya by University of Illinois at Chicago researchers.

Three clinical trials have shown that male circumcision significantly reduces the risk of acquiring HIV in young African men. However, some experts have suggested that circumcision, if promoted as an HIV preventive, may increase promiscuity or decrease condom use. This 'risk compensation' could diminish the effectiveness of medical male circumcision programs.

The new study, published online July 21 in the journal AIDS and ...

Brain waves show learning to read does not end in 4th grade, contrary to popular theory

2014-07-21

Teachers-in-training have long been taught that fourth grade is when students stop learning to read and start reading to learn. But a new Dartmouth study in the journal Developmental Science tested the theory by analyzing brain waves and found that fourth-graders do not experience a change in automatic word processing, a crucial component of the reading shift theory. Instead, some types of word processing become automatic before fourth grade, while others don't switch until after fifth.

The findings mean that teachers at all levels of elementary school must think of themselves ...

Large twin study suggests that language delay due more to nature than nurture

2014-07-21

A study of 473 sets of twins followed since birth found that compared to single-born children, 47 percent of 24-month-old identical twins had language delay compared to 31 percent of non-identical twins. Overall, twins had twice the rate of late language emergence of single-born children. None of the children had disabilities affecting language acquisition.

The results of the study were published in the June 2014 Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research.

University of Kansas Distinguished Professor Mabel Rice, lead author, said that all of the language traits ...

Study examines incentives to increase medical male circumcision to help reduce risk of HIV

2014-07-21

Among uncircumcised men in Kenya, compensation in the form of food vouchers worth approximately U.S. $9 or $15, compared with lesser or no compensation, resulted in a modest increase in the prevalence of circumcision after 2 months, according to a study published by JAMA. The study is being released to coincide with its presentation at the International AIDS Conference.

Following randomized trials that demonstrated that medical male circumcision reduces men's risk of HIV acquisition by 50 percent to 60 percent, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization recommended the ...

Fecal transplants let packrats eat poison

2014-07-21

Salt Lake City – Woodrats lost their ability to eat toxic creosote bushes after antibiotics killed their gut microbes. Woodrats that never ate the plants were able to do so after receiving fecal transplants with microbes from creosote-eaters, University of Utah biologists found.

The new study confirms what biologists long have suspected: bacteria in the gut – and not just liver enzymes – are "crucial in allowing herbivores to feed on toxic plants," says biologist Kevin Kohl, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper published online today in the journal ...

Why are more people in the UK complaining about their doctors?

2014-07-21

The report – "Understanding the Rise in Fitness to Practise Complaints from Members of the General Public" – is published today.

An increase in complaints has been seen across the UK, which suggests wider social trends rather than localised issues. A large number of complaints did not progress because the issues raised could not be identified, which suggests that the GMC is receiving complaints outside its remit. According to the report, this points towards problems with the wider complaint-handling system and culture.

While the report does not point to any specific ...

UEA research shows oceans vital for possibility for alien life

2014-07-21

Researchers at the University of East Anglia have made an important step in the race to discover whether other planets could develop and sustain life.

New research published today in the journal Astrobiology shows the vital role of oceans in moderating climate on Earth-like planets.

Until now, computer simulations of habitable climates on Earth-like planets have focused on their atmospheres. But the presence of oceans is vital for optimal climate stability and habitability.

The research team from UEA's schools of Maths and Environmental Sciences created a computer ...

New findings show strikingly early seeding of HIV viral reservoir

2014-07-20

BOSTON – The most critical barrier for curing HIV-1 infection is the presence of the viral reservoir, the cells in which the HIV virus can lie dormant for many years and avoid elimination by antiretroviral drugs. Very little has been known about when and where the viral reservoir is established during acute HIV-1 infection, or the extent to which it is susceptible to early antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Now a research team led by investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in collaboration with the U.S. Military HIV Research Program has demonstrated that ...