(Press-News.org) Salt Lake City – Woodrats lost their ability to eat toxic creosote bushes after antibiotics killed their gut microbes. Woodrats that never ate the plants were able to do so after receiving fecal transplants with microbes from creosote-eaters, University of Utah biologists found.

The new study confirms what biologists long have suspected: bacteria in the gut – and not just liver enzymes – are "crucial in allowing herbivores to feed on toxic plants," says biologist Kevin Kohl, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper published online today in the journal Ecology Letters.

The study of woodrats, also known as packrats, raises two concerns, according to Kohl and the study's senior author, Denise Dearing, a professor and chair of biology:

Endangered species may lose diversity of their gut microbes when they are bred in captivity. When they are released to the wild, does that leave them unable to consume toxic plants that once were on their menu?

Livestock like cows often are fed antibiotics to promote growth. Does that impair their ability to eat toxic plants like locoweed when drought reduces pasture grass?

The study of woodrats someday might impact farming practices in arid regions, where toxic plants like creosote and juniper are abundant. Livestock now can't graze on these cheap food sources. Could interspecies transplants of gut microbes help livestock expand their dining menu? Kohl says he'd like to transplant woodrat gut microbes into sheep or goats to find out if that increases their tolerance to toxic foods.

"Juniper is expanding its range, and ecologists and land managers are concerned," he says. "Farmers are interested in getting their sheep and goats to eat juniper."

Evolving a Taste for Toxins

Many plants produce toxic chemicals, which they use as a defense against herbivores, or plant-eating animals. A toxic resin coats the leaves of the creosote bush; juniper toxins are found inside juniper needles.

Most mammals are herbivores. Some face serious challenges: their bodies must handle up to hundreds of toxic chemicals from the plants they consume each day. "Plant toxins determine which plants a herbivore can eat," says Kohl.

Liver enzymes help animals detoxify such poisons. Researchers previously isolated toxin-degrading microbes from herbivores, but Kohl and Dearing say that, until now, scientists have lacked strong evidence for what has been conventional wisdom: Gut microbes also help some herbivores eat toxic plants.

The study involved desert woodrats (Neotoma lepida) – grayish rodents native to western North American deserts. Woodrats somehow acquired novel toxin-degrading gut microbes to adapt to climate and vegetation changes that began 17,000 years ago.

"In a natural climatic event at the end of the last glacial period, the Southwest dried out and our major deserts were formed," Dearing says. Creosote, which was native to Mexico, moved north into the Mojave Desert and replaced juniper there, but did not go farther north into Great Basin deserts. Desert woodrats in the Mojave started eating creosote bushes, while desert woodrats in the Great Basin kept eating toxic juniper, to which they had adapted earlier.

At first, the ancient juniper eaters in the Mojave likely were poorly equipped to eat invading creosote, but scientists believe microbes sped up their dietary adjustment. Though slow, evolutionary genetic changes in herbivores play an important role in adapting to new diets. "Transfer of toxin-degrading microbes from one organism to the other is much more rapid," Dearing says.

How do woodrats get their tiny, but valuable bacterial helpers today?

"Mammals acquire microbes during birth, through contact with their mother's vaginal and fecal microbes," Kohl says. "Other possible places to get microbes include leaf surfaces, the soil or feces that woodrats collect from other animals."

Speeding Up Dietary Evolution with Fecal Transplants

In an earlier study, the Utah researchers showed that the creosote-eating woodrats from the Sonoran and Mojave deserts had higher proportions of gut microbes that might detoxify creosote, while juniper-eating woodrats from the Great Basin had a different set of gut bacteria.

In the new study, Dearing and colleagues performed three experiments using two kinds of woodrats -- juniper eaters from the Great Basin desert and creosote eaters from the Mojave Desert. They were captured and kept in the lab on a diet of rabbit chow.

In the first experiment, the scientists studied the relative abundances of gut-microbe genes in two groups of the creosote-eating Mojave woodrats. One group was fed rabbit chow containing 1 percent of creosote resin for two days, followed by rabbit chow with 2 percent of creosote resin for three days. The control group was fed only rabbit chow. Gut microbes were removed from the foreguts of both woodrat groups. DNA was isolated from the microbes to identify genes involved in detoxification.

The scientists found that a woodrat's diet determines the composition of its gut microbes. "Mammals are adapted to the plant toxins they eat," Kohl says. The guts of creosote-fed woodrats were teeming with microbes that may degrade creosote, while the guts of creosote-free woodrats had only one-fourth the levels of the same gut microbes.

In the second experiment, the researchers experimentally removed gut microbes to highlight their dietary role in woodrats. Antibiotics kill about 90 percent of the gut microbes in animals, severely impairing their ability to consume toxic foods.

Two groups of woodrats were pretreated with the antibiotic neomycin in their drinking water. One group was placed on a diet of rabbit chow and creosote resin. With their gut microbes killed by the antibiotic, they were unable to feed on creosote and lost 10 percent of their body weight within 13 days. The second group ate only rabbit chow and didn't lose weight, showing that killing their gut microbes didn't harm them because they weren't eating toxic creosote.

In the third experiment, the biologists essentially sped up evolution by using fecal transplants to quickly change populations of microbes living in the woodrats' guts. They conducted fecal transplants and showed that acquiring new microbes indeed helped woodrats adopt new diets.

Woodrats naturally eat their own and other woodrats' feces. So in the experiment, juniper-eating Great Basin woodrats were fed rabbit chow mixed with feces either from other juniper eaters or from creosote-eating Mojave woodrats. Both woodrat groups then were challenged with a creosote diet.

After ingesting feces – and thus gut microbes – from creosote eaters, juniper eaters persisted for 11 days on the creosote diet without losing much weight. Yet 65 percent of the juniper eaters that ate feces of other juniper eaters didn't gain microbes that detoxify creosote, so they lost 10 percent of their weight by day 11 on a creosote diet.

It's not that those woodrats rejected creosote-laced food. They ate as much as the woodrats that were fed feces with creosote-detoxifying microbes. Instead, Kohl and co-authors found that when woodrats didn't get transplants of creosote-detoxifying microbes, their urine was more acidic, suggesting their livers expended a lot of energy to degrade creosote toxins.

But in juniper eaters that consumed the feces of creosote eaters, their newly acquired gut microbes likely detoxified most of the creosote, taking the burden off of liver enzymes.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation. Dearing and Kohl conducted the research with three other University of Utah faculty members: human geneticist Robert Weiss, biochemist James Cox and biologist Colin Dale.

University of Utah Communications

75 Fort Douglas Boulevard,

Salt Lake City, UT 84113

801-581-6773

Fax: 801-585-3350

http://www.unews.utah.edu

Fecal transplants let packrats eat poison

Herbivores dine on toxic plants, thanks to gut microbes

2014-07-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Why are more people in the UK complaining about their doctors?

2014-07-21

The report – "Understanding the Rise in Fitness to Practise Complaints from Members of the General Public" – is published today.

An increase in complaints has been seen across the UK, which suggests wider social trends rather than localised issues. A large number of complaints did not progress because the issues raised could not be identified, which suggests that the GMC is receiving complaints outside its remit. According to the report, this points towards problems with the wider complaint-handling system and culture.

While the report does not point to any specific ...

UEA research shows oceans vital for possibility for alien life

2014-07-21

Researchers at the University of East Anglia have made an important step in the race to discover whether other planets could develop and sustain life.

New research published today in the journal Astrobiology shows the vital role of oceans in moderating climate on Earth-like planets.

Until now, computer simulations of habitable climates on Earth-like planets have focused on their atmospheres. But the presence of oceans is vital for optimal climate stability and habitability.

The research team from UEA's schools of Maths and Environmental Sciences created a computer ...

New findings show strikingly early seeding of HIV viral reservoir

2014-07-20

BOSTON – The most critical barrier for curing HIV-1 infection is the presence of the viral reservoir, the cells in which the HIV virus can lie dormant for many years and avoid elimination by antiretroviral drugs. Very little has been known about when and where the viral reservoir is established during acute HIV-1 infection, or the extent to which it is susceptible to early antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Now a research team led by investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in collaboration with the U.S. Military HIV Research Program has demonstrated that ...

Metabolic enzyme stops progression of most common type of kidney cancer

2014-07-20

PHILADELPHIA -- In an analysis of small molecules called metabolites used by the body to make fuel in normal and cancerous cells in human kidney tissue, a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania identified an enzyme key to applying the brakes on tumor growth. The team found that an enzyme called FBP1 – essential for regulating metabolism – binds to a transcription factor in the nucleus of certain kidney cells and restrains energy production in the cell body. What's more, they determined that this enzyme is missing from all kidney ...

Scientists map one of most important proteins in life -- and cancer

2014-07-20

Scientists reveal the structure of one of the most important and complicated proteins in cell division – a fundamental process in life and the development of cancer – in research published in Nature today (Sunday).

Images of the gigantic protein in unprecedented detail will transform scientists' understanding of exactly how cells copy their chromosomes and divide, and could reveal binding sites for future cancer drugs.

A team from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge produced the first ...

Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution

2014-07-20

HOUSTON – (July 20, 2014) – A team of scientists from around the world led by Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University in St. Louis has completed the genome sequence of the common marmoset – the first sequence of a New World Monkey – providing new information about the marmoset's unique rapid reproductive system, physiology and growth, shedding new light on primate biology and evolution.

The team published the work today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We study primate genomes to get a better understanding of the biology of the species that are most closely ...

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional ...

Common gene variants account for most genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

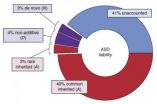

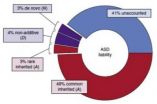

Most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have found. Heritability also outweighed other risk factors in this largest study of its kind to date.

About 52 percent of the risk for autism was traced to common and rare inherited variation, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk.

"Genetic variation likely accounts for roughly 60 percent of the liability for autism, ...

Genetic risk for autism stems mostly from common genes

2014-07-20

PITTSBURGH—Using new statistical tools, Carnegie Mellon University's Kathryn Roeder has led an international team of researchers to discover that most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches.

Published in the July 20 issue of the journal "Nature Genetics," the study found that about 52 percent of autism was traced to common genes and rarely inherited variations, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk. The research team — ...

A noble gas cage

2014-07-20

Richland, Wash. -- When nuclear fuel gets recycled, the process releases radioactive krypton and xenon gases. Naturally occurring uranium in rock contaminates basements with the related gas radon. A new porous material called CC3 effectively traps these gases, and research appearing July 20 in Nature Materials shows how: by breathing enough to let the gases in but not out.

The CC3 material could be helpful in removing unwanted or hazardous radioactive elements from nuclear fuel or air in buildings and also in recycling useful elements from the nuclear fuel cycle. CC3 ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

[Press-News.org] Fecal transplants let packrats eat poisonHerbivores dine on toxic plants, thanks to gut microbes