(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA -- In an analysis of small molecules called metabolites used by the body to make fuel in normal and cancerous cells in human kidney tissue, a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania identified an enzyme key to applying the brakes on tumor growth. The team found that an enzyme called FBP1 – essential for regulating metabolism – binds to a transcription factor in the nucleus of certain kidney cells and restrains energy production in the cell body. What's more, they determined that this enzyme is missing from all kidney tumor tissue analyzed. These tumor cells without FBP1 produce energy at a much faster rate than their non-cancer cell counterparts. When FBP1 is working properly, out-of-control cell growth is kept in check.

The new study, published online this week in Nature, was led by Celeste Simon, PhD, a professor of Cell and Developmental Biology and the scientific director for the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute at Penn.

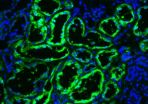

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), the most frequent form of kidney cancer, is characterized by elevated glycogen (a form of carbohydrate) and fat deposits in affected kidney cells. This over-storage of lipids causes large clear droplets to accumulate, hence the cancer's name.

In the last decade, ccRCCs have been on the rise worldwide. However, if tumors are removed early, a patient's prognosis for five-year survival is relatively good. If expression of the FBP1 gene is lost, patients have a worse prognosis.

"This study is the first stop in this line of research for coming up with a personalized approach for people with clear cell renal cell carcinoma-related mutations," says Simon, also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

A Series of Faulty Reactions

The aberrant storage of lipid in ccRCC results from a faulty series of biochemical reactions. These reactions, called the Kreb's cycle, generate energy from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in the form of ATP. However, the Kreb's cycle is hyperactive in ccRCC, resulting in enhanced lipid production. Renal cancer cells are associated with changes in two important intracellular proteins: elevated expression of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) and mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) encoded protein, pVHL. In fact, mutations in pVHL occur in 90 percent of ccRCC tumors. pVHL regulates HIFs, which in turn affect activity of the Kreb's cycle.

Although much is already known about metabolic pathways and their role in cancer, there are still important questions to be answered. For example, kidney-specific VHL deletion in mice does not elicit clear cell-specific tumor formation, suggesting that additional mechanisms are at play. Toward answering that hunch, recent large-scale sequencing analyses have revealed the loss of several epigenetic enzymes in certain types of ccRCCs, suggesting that changes within the nucleus also account for kidney tumor progression.

To complement genetic studies revealing a role for epigenetic enzymes, the team evaluated metabolic enzymes in the 600-plus tumors they analyzed. The expression of FBP1 was lost in all kidney cancer tissue samples examined. They found FBP1 protein in the cytoplasm of normal cells, where it would be expected to be active in glucose metabolism. But, they also found FBP1 in the nucleus of these normal cells, where it binds to HIF to modulate its effects on tumor growth. In cells without FBPI, the team observed the Warburg effect – a phenomenon in which malignant, rapidly growing tumor cells go into overdrive, producing energy up to 200 times faster than their non-cancer-cell counterparts.

This unique dual function of FBP1 explains its ubiquitous loss in ccRCC, distinguishing FBP1 from previously identified tumor suppressors that are not consistently inhibited in all tumors. "And since FBP1 activity is also lost in liver cancer, which is quite prevalent, FBP1 depletion may be generally applicable to a number of human cancers," notes Simon.

Next steps, according to the researchers, will be to identify other metabolic pathways to target, measure the abundance of metabolites in kidney and liver cancer cells to determine FBP1's role in each, and develop a better mouse model for preclinical studies.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are Bo Li, Bo Qiu, David S.M. Lee, Zandra E. Walton, Joshua D. Ochocki, Lijoy K. Mathew, Anthony Mancuso, Terence P.F. Gade, and Brian Keith, all from Penn, as well as

Itzhak Nissim, from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $392 million awarded in the 2013 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2013, Penn Medicine provided $814 million to benefit our community.

Metabolic enzyme stops progression of most common type of kidney cancer

Enzyme lost in 100 percent of tumors analyzed, Penn study finds

2014-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists map one of most important proteins in life -- and cancer

2014-07-20

Scientists reveal the structure of one of the most important and complicated proteins in cell division – a fundamental process in life and the development of cancer – in research published in Nature today (Sunday).

Images of the gigantic protein in unprecedented detail will transform scientists' understanding of exactly how cells copy their chromosomes and divide, and could reveal binding sites for future cancer drugs.

A team from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge produced the first ...

Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution

2014-07-20

HOUSTON – (July 20, 2014) – A team of scientists from around the world led by Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University in St. Louis has completed the genome sequence of the common marmoset – the first sequence of a New World Monkey – providing new information about the marmoset's unique rapid reproductive system, physiology and growth, shedding new light on primate biology and evolution.

The team published the work today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We study primate genomes to get a better understanding of the biology of the species that are most closely ...

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional ...

Common gene variants account for most genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

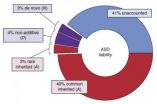

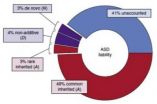

Most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have found. Heritability also outweighed other risk factors in this largest study of its kind to date.

About 52 percent of the risk for autism was traced to common and rare inherited variation, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk.

"Genetic variation likely accounts for roughly 60 percent of the liability for autism, ...

Genetic risk for autism stems mostly from common genes

2014-07-20

PITTSBURGH—Using new statistical tools, Carnegie Mellon University's Kathryn Roeder has led an international team of researchers to discover that most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches.

Published in the July 20 issue of the journal "Nature Genetics," the study found that about 52 percent of autism was traced to common genes and rarely inherited variations, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk. The research team — ...

A noble gas cage

2014-07-20

Richland, Wash. -- When nuclear fuel gets recycled, the process releases radioactive krypton and xenon gases. Naturally occurring uranium in rock contaminates basements with the related gas radon. A new porous material called CC3 effectively traps these gases, and research appearing July 20 in Nature Materials shows how: by breathing enough to let the gases in but not out.

The CC3 material could be helpful in removing unwanted or hazardous radioactive elements from nuclear fuel or air in buildings and also in recycling useful elements from the nuclear fuel cycle. CC3 ...

New method for extracting radioactive elements from air and water

2014-07-20

LIVERPOOL, UK – 20 July 2014: Scientists at the University of Liverpool have successfully tested a material that can extract atoms of rare or dangerous elements such as radon from the air.

Gases such as radon, xenon and krypton all occur naturally in the air but in minute quantities – typically less than one part per million. As a result they are expensive to extract for use in industries such as lighting or medicine and, in the case of radon, the gas can accumulate in buildings. In the US alone, radon accounts for around 21,000 lung cancer deaths a year.

Previous ...

Singapore scientists discover genetic cause of common breast tumours in women

2014-07-20

Singapore, 21 July 2014 – A multi-disciplinary team of scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore, and Singapore General Hospital have made a seminal breakthrough in understanding the molecular basis of fibroadenoma, one of the most common breast tumours diagnosed in women. The team, led by Professors Teh Bin Tean, Patrick Tan, Tan Puay Hoon and Steve Rozen, used advanced DNA sequencing technologies to identify a critical gene called MED12 that was repeatedly disrupted in nearly 60% of fibroadenoma cases. Their findings ...

New technique maps life's effects on our DNA

2014-07-20

Researchers at the BBSRC-funded Babraham Institute, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Single Cell Genomics Centre, have developed a powerful new single-cell technique to help investigate how the environment affects our development and the traits we inherit from our parents. The technique can be used to map all of the 'epigenetic marks' on the DNA within a single cell. This single-cell approach will boost understanding of embryonic development, could enhance clinical applications like cancer therapy and fertility treatments, and has the potential ...

CU, Old Dominion team finds sea level rise in western tropical Pacific anthropogenic

2014-07-20

A new study led by Old Dominion University and the University of Colorado Boulder indicates sea levels likely will continue to rise in the tropical Pacific Ocean off the coasts of the Philippines and northeastern Australia as humans continue to alter the climate.

The study authors combined past sea level data gathered from both satellite altimeters and traditional tide gauges as part of the study. The goal was to find out how much a naturally occurring climate phenomenon called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or PDO, influences sea rise patterns in the Pacific, said ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Metabolic enzyme stops progression of most common type of kidney cancerEnzyme lost in 100 percent of tumors analyzed, Penn study finds