(Press-News.org) BOSTON – The most critical barrier for curing HIV-1 infection is the presence of the viral reservoir, the cells in which the HIV virus can lie dormant for many years and avoid elimination by antiretroviral drugs. Very little has been known about when and where the viral reservoir is established during acute HIV-1 infection, or the extent to which it is susceptible to early antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Now a research team led by investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in collaboration with the U.S. Military HIV Research Program has demonstrated that the viral reservoir is established strikingly early after intrarectal simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of rhesus monkeys and before detectable viremia.

The findings appear online in the journal Nature.

"Our data show that in this animal model, the viral reservoir was seeded substantially earlier after infection than was previously recognized," explains senior author Dan H. Barouch, MD, PhD, Director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at BIDMC and steering committee member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard. "We found that the reservoir was established in tissues during the first few days of infection, before the virus was even detected in the blood."

This discovery coincides with the recently reported news of the HIV resurgence in the "Mississippi baby," who was believed to have been cured by early administration of ART. "The unfortunate news of the virus rebounding in this child further emphasizes the need to understand the early and refractory viral reservoir that is established very quickly following HIV infection in humans," adds Barouch, a Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

In this new study, the scientific team initiated suppressive ART in groups of monkeys on days 3, 7, 10 and 14 after intrarectal SIV infection. Animals treated on day 3 following infection showed no evidence of virus in the blood and did not generate any SIV-specific immune responses. Nevertheless, after six months of suppressive ART, all of the animals in the study exhibited viral resurgence when treatment was stopped.

While early initiation of ART did result in a delay in the time to viral rebound (the time it takes for virus replication to be observed in the blood following cessation of ART) as compared with later treatment, the inability to eradicate the viral reservoir with very early initiation of ART suggests that additional strategies will be needed to cure HIV infection.

"The strikingly early seeding of the viral reservoir within the first few days of infection is sobering and presents new challenges to HIV-1 eradication efforts," the authors write. "Taken together, our data suggest that extremely early initiation of ART, extended ART duration, and probably additional interventions that activate the viral reservoir will be required for HIV-1 eradication."

INFORMATION:

Study coauthors include first author James Whitney of BIDMC and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard; BIDMC investigators Srisowmya Sanisetty, Pablo Penaloz-MacMaster, Jinyan Liu, Mayuri Shetty, Lily Parenteau, Crystal Cabral, Jennifers Shields, Stephen Blackmore, Jeffrey Y. Smith, Amanda L. Brinkman, Lauren E. Peter, Sheeba I. Mathew, Kaitlin M. Smith, Erica N. Borducchi; Aliso L. Hill and Daniel I. S. Rosenbloom of Harvard University; Mark G. Lewis of Bioqual, Rockville, MD; Jillian Hattersley, Bei Li, Joseph Hesselgesser, Romas Geleziunas of Gileas Sciences, Foster City, CA; and Merlin L. Robb, Jerome H. Kim and Nelson L. Michael of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

This study was supported, in part, by the US Military Research and Material Command and the US Military HIV Research Program through its cooperative agreement with the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (W81XWH-07-2-0067; W81XWH-11-2-0174); the National Institutes of Health (AI060354; AI078526; AI084794; AI095985; AI096040; AI100645) and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is a patient care, teaching and research affiliate of Harvard Medical School, and currently ranks third in National Institutes of Health funding among independent hospitals nationwide.

BIDMC is in the community with Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Milton, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Needham, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Plymouth, Anna Jaques Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Lawrence General Hospital, Signature Health Care, Beth Israel Deaconess HealthCare, Community Care Alliance, and Atrius Health. BIDMC is also clinically affiliated with the Joslin Diabetes Center and Hebrew Senior Life and is a research partner of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. BIDMC is the official hospital of the Boston Red Sox. For more information, visit http://www.bidmc.org.

New findings show strikingly early seeding of HIV viral reservoir

Discovery presents new challenges for HIV eradication efforts

2014-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Metabolic enzyme stops progression of most common type of kidney cancer

2014-07-20

PHILADELPHIA -- In an analysis of small molecules called metabolites used by the body to make fuel in normal and cancerous cells in human kidney tissue, a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania identified an enzyme key to applying the brakes on tumor growth. The team found that an enzyme called FBP1 – essential for regulating metabolism – binds to a transcription factor in the nucleus of certain kidney cells and restrains energy production in the cell body. What's more, they determined that this enzyme is missing from all kidney ...

Scientists map one of most important proteins in life -- and cancer

2014-07-20

Scientists reveal the structure of one of the most important and complicated proteins in cell division – a fundamental process in life and the development of cancer – in research published in Nature today (Sunday).

Images of the gigantic protein in unprecedented detail will transform scientists' understanding of exactly how cells copy their chromosomes and divide, and could reveal binding sites for future cancer drugs.

A team from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge produced the first ...

Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution

2014-07-20

HOUSTON – (July 20, 2014) – A team of scientists from around the world led by Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University in St. Louis has completed the genome sequence of the common marmoset – the first sequence of a New World Monkey – providing new information about the marmoset's unique rapid reproductive system, physiology and growth, shedding new light on primate biology and evolution.

The team published the work today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We study primate genomes to get a better understanding of the biology of the species that are most closely ...

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional ...

Common gene variants account for most genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

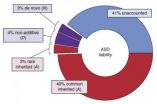

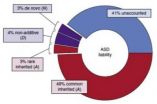

Most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have found. Heritability also outweighed other risk factors in this largest study of its kind to date.

About 52 percent of the risk for autism was traced to common and rare inherited variation, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk.

"Genetic variation likely accounts for roughly 60 percent of the liability for autism, ...

Genetic risk for autism stems mostly from common genes

2014-07-20

PITTSBURGH—Using new statistical tools, Carnegie Mellon University's Kathryn Roeder has led an international team of researchers to discover that most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches.

Published in the July 20 issue of the journal "Nature Genetics," the study found that about 52 percent of autism was traced to common genes and rarely inherited variations, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk. The research team — ...

A noble gas cage

2014-07-20

Richland, Wash. -- When nuclear fuel gets recycled, the process releases radioactive krypton and xenon gases. Naturally occurring uranium in rock contaminates basements with the related gas radon. A new porous material called CC3 effectively traps these gases, and research appearing July 20 in Nature Materials shows how: by breathing enough to let the gases in but not out.

The CC3 material could be helpful in removing unwanted or hazardous radioactive elements from nuclear fuel or air in buildings and also in recycling useful elements from the nuclear fuel cycle. CC3 ...

New method for extracting radioactive elements from air and water

2014-07-20

LIVERPOOL, UK – 20 July 2014: Scientists at the University of Liverpool have successfully tested a material that can extract atoms of rare or dangerous elements such as radon from the air.

Gases such as radon, xenon and krypton all occur naturally in the air but in minute quantities – typically less than one part per million. As a result they are expensive to extract for use in industries such as lighting or medicine and, in the case of radon, the gas can accumulate in buildings. In the US alone, radon accounts for around 21,000 lung cancer deaths a year.

Previous ...

Singapore scientists discover genetic cause of common breast tumours in women

2014-07-20

Singapore, 21 July 2014 – A multi-disciplinary team of scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore, and Singapore General Hospital have made a seminal breakthrough in understanding the molecular basis of fibroadenoma, one of the most common breast tumours diagnosed in women. The team, led by Professors Teh Bin Tean, Patrick Tan, Tan Puay Hoon and Steve Rozen, used advanced DNA sequencing technologies to identify a critical gene called MED12 that was repeatedly disrupted in nearly 60% of fibroadenoma cases. Their findings ...

New technique maps life's effects on our DNA

2014-07-20

Researchers at the BBSRC-funded Babraham Institute, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Single Cell Genomics Centre, have developed a powerful new single-cell technique to help investigate how the environment affects our development and the traits we inherit from our parents. The technique can be used to map all of the 'epigenetic marks' on the DNA within a single cell. This single-cell approach will boost understanding of embryonic development, could enhance clinical applications like cancer therapy and fertility treatments, and has the potential ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

AI biases can influence people’s perception of history

Prenatal opioid exposure and well-being through adolescence

Big and small dogs both impact indoor air quality, just differently

Wearing a weighted vest to strengthen bones? Make sure you’re moving

Microbe survives the pressures of impact-induced ejection from Mars

Asteroid samples offer new insights into conditions when the solar system formed

Fecal transplants from older mice significantly improve ovarian function and fertility in younger mice

Delight for diastereomer production: A novel strategy for organic chemistry

Permafrost is key to carbon storage. That makes northern wildfires even more dangerous

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

Genetic risk for mental illness is far less disorder-specific than clinicians have assumed, massive Swedish study reveals

A therapeutic target that would curb the spread of coronaviruses has been identified

Modern twist on wildfire management methods found also to have a bonus feature that protects water supplies

AI enables defect-aware prediction of metal 3D-printed part quality

Miniscule fossil discovery reveals fresh clues into the evolution of the earliest-known relative of all primates

World Water Day 2026: Applied Microbiology International to hold Gender Equality and Water webinar

The unprecedented transformation in energy: The Third Energy Revolution toward carbon neutrality

Building on the far side: AI analysis suggests sturdier foundation for future lunar bases

Far-field superresolution imaging via k-space superoscillation

10 Years, 70% shift: Wastewater upgrades quietly transform river microbiomes

Why does chronic back pain make everyday sounds feel harsher? Brain imaging study points to a treatable cause

Video messaging effectiveness depends on quality of streaming experience, research shows

Introducing the “bloom” cycle, or why plants are not stupid

The Lancet Oncology: Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide, with annual cases expected to reach over 3.5 million by 2050

Improve education and transitional support for autistic people to prevent death by suicide, say experts

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic could cut risk of major heart complications after heart attack, study finds

Study finds Earth may have twice as many vertebrate species as previously thought

NYU Langone orthopedic surgeons present latest clinical findings and research at AAOS 2026

New journal highlights how artificial intelligence can help solve global environmental crises

Study identifies three diverging global AI pathways shaping the future of technology and governance

[Press-News.org] New findings show strikingly early seeding of HIV viral reservoirDiscovery presents new challenges for HIV eradication efforts