(Press-News.org) Teachers-in-training have long been taught that fourth grade is when students stop learning to read and start reading to learn. But a new Dartmouth study in the journal Developmental Science tested the theory by analyzing brain waves and found that fourth-graders do not experience a change in automatic word processing, a crucial component of the reading shift theory. Instead, some types of word processing become automatic before fourth grade, while others don't switch until after fifth.

The findings mean that teachers at all levels of elementary school must think of themselves as reading instructors, said the study's author, Associate Professor of Education Donna Coch.

"Until now, we lacked neurological evidence about the supposed fourth-grade shift," said Coch, also principal investigator for Dartmouth's Reading Brains Lab. "The theory developed from behavioral evidence, and as a result of it, some teachers in fifth and sixth grade have not thought of themselves as reading instructors. Now we can see from brain waves that students in those grades are still learning to process words automatically; their neurological reading system is not yet adult-like."

Automatic word processing is the brain's ability to determine whether a group of symbols constitutes a word within milliseconds, without the brain's owner realizing the process is taking place.

To test how automatic word processing develops, Coch placed electrode caps on the heads of third-, fourth-, and fifth-graders, as well as college students. She had her test subjects view a screen that displayed a mix of real English words (such as "bed"), pseudo-words (such as "bem"), strings of letters (such as "mbe"), and strings of meaningless symbols one at a time. The setup allowed her to see how the subjects' brains reacted to each kind of stimulus within milliseconds. In other words, she could watch their automatic word processing.

Next, Coch gave the participants a written test, in which they were asked to circle the real words in a list that also contained pseudo-words, strings of letters, and strings of meaningless symbols. This task was designed to test the participants' conscious word processing, a much slower procedure.

Interestingly, most of the 96 participants got a nearly perfect score on the written test, showing that their conscious brains knew the difference between words and non-words.

However, the electrode cap revealed that only the college students processed meaningless symbols differently than real words. The third-, fourth-, and fifth-graders' brains reacted to the meaningless symbols the same way they reacted to common English words.

"This tells us that, at least through the fifth grade, even children who read well are letting stimuli into the neural word processing system that more mature readers do not," Coch said. "Their brains are processing strings of meaningless symbols as if they were words, perhaps in case they turn out to be real letters. In contrast, by college, students have learned not to process strings of meaningless symbols as words, saving their brains precious time and energy."

The phenomenon is evidence that young readers do not fully develop automatic word processing skills until after fifth grade, which contradicts the fourth-grade reading shift theory.

The brain waves also showed that the third-, fourth-, and fifth-graders processed real words, psuedowords, and letter strings similarly to college students, suggesting that some automatic word processing begins before the fourth grade, and even before the third grade, also contradicting the reading shift theory.

"There is value to the theory of the fourth grade shift in that it highlights how reading skills and abilities develop at different times," Coch said. "But the neural data suggest that teachers should not expect their fourth-graders, or even their fifth-graders, to be completely automatic, adult-like readers."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Professor Coch is available to comment at Donna.J.Coch@Dartmouth.edu or (603) 646-3282.

Dartmouth has TV and radio studios available for interviews. For more information, visit: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~opa/radio-tv-studios/

Brain waves show learning to read does not end in 4th grade, contrary to popular theory

2014-07-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Large twin study suggests that language delay due more to nature than nurture

2014-07-21

A study of 473 sets of twins followed since birth found that compared to single-born children, 47 percent of 24-month-old identical twins had language delay compared to 31 percent of non-identical twins. Overall, twins had twice the rate of late language emergence of single-born children. None of the children had disabilities affecting language acquisition.

The results of the study were published in the June 2014 Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research.

University of Kansas Distinguished Professor Mabel Rice, lead author, said that all of the language traits ...

Study examines incentives to increase medical male circumcision to help reduce risk of HIV

2014-07-21

Among uncircumcised men in Kenya, compensation in the form of food vouchers worth approximately U.S. $9 or $15, compared with lesser or no compensation, resulted in a modest increase in the prevalence of circumcision after 2 months, according to a study published by JAMA. The study is being released to coincide with its presentation at the International AIDS Conference.

Following randomized trials that demonstrated that medical male circumcision reduces men's risk of HIV acquisition by 50 percent to 60 percent, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization recommended the ...

Fecal transplants let packrats eat poison

2014-07-21

Salt Lake City – Woodrats lost their ability to eat toxic creosote bushes after antibiotics killed their gut microbes. Woodrats that never ate the plants were able to do so after receiving fecal transplants with microbes from creosote-eaters, University of Utah biologists found.

The new study confirms what biologists long have suspected: bacteria in the gut – and not just liver enzymes – are "crucial in allowing herbivores to feed on toxic plants," says biologist Kevin Kohl, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper published online today in the journal ...

Why are more people in the UK complaining about their doctors?

2014-07-21

The report – "Understanding the Rise in Fitness to Practise Complaints from Members of the General Public" – is published today.

An increase in complaints has been seen across the UK, which suggests wider social trends rather than localised issues. A large number of complaints did not progress because the issues raised could not be identified, which suggests that the GMC is receiving complaints outside its remit. According to the report, this points towards problems with the wider complaint-handling system and culture.

While the report does not point to any specific ...

UEA research shows oceans vital for possibility for alien life

2014-07-21

Researchers at the University of East Anglia have made an important step in the race to discover whether other planets could develop and sustain life.

New research published today in the journal Astrobiology shows the vital role of oceans in moderating climate on Earth-like planets.

Until now, computer simulations of habitable climates on Earth-like planets have focused on their atmospheres. But the presence of oceans is vital for optimal climate stability and habitability.

The research team from UEA's schools of Maths and Environmental Sciences created a computer ...

New findings show strikingly early seeding of HIV viral reservoir

2014-07-20

BOSTON – The most critical barrier for curing HIV-1 infection is the presence of the viral reservoir, the cells in which the HIV virus can lie dormant for many years and avoid elimination by antiretroviral drugs. Very little has been known about when and where the viral reservoir is established during acute HIV-1 infection, or the extent to which it is susceptible to early antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Now a research team led by investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in collaboration with the U.S. Military HIV Research Program has demonstrated that ...

Metabolic enzyme stops progression of most common type of kidney cancer

2014-07-20

PHILADELPHIA -- In an analysis of small molecules called metabolites used by the body to make fuel in normal and cancerous cells in human kidney tissue, a research team from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania identified an enzyme key to applying the brakes on tumor growth. The team found that an enzyme called FBP1 – essential for regulating metabolism – binds to a transcription factor in the nucleus of certain kidney cells and restrains energy production in the cell body. What's more, they determined that this enzyme is missing from all kidney ...

Scientists map one of most important proteins in life -- and cancer

2014-07-20

Scientists reveal the structure of one of the most important and complicated proteins in cell division – a fundamental process in life and the development of cancer – in research published in Nature today (Sunday).

Images of the gigantic protein in unprecedented detail will transform scientists' understanding of exactly how cells copy their chromosomes and divide, and could reveal binding sites for future cancer drugs.

A team from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge produced the first ...

Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution

2014-07-20

HOUSTON – (July 20, 2014) – A team of scientists from around the world led by Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University in St. Louis has completed the genome sequence of the common marmoset – the first sequence of a New World Monkey – providing new information about the marmoset's unique rapid reproductive system, physiology and growth, shedding new light on primate biology and evolution.

The team published the work today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We study primate genomes to get a better understanding of the biology of the species that are most closely ...

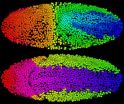

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional ...