(Press-News.org) Scientists have pinpointed for the first time the genetic cause in some people of an incurable muscle-wasting disease, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD).

The international research team led by the University of Leicester say the finding of two target genes opens the possibility of developing drugs to tackle the disease in these patients. Their work has been published today in the journal PLOS Genetics.

The research was funded by The Wellcome Trust and was only possible by the University of Leicester team collaborating with groups in Germany (University of Greifswald), Italy (Institute of Molecular Genetics, Bologna, Italy) and the USA (Columbia University).

To date, only six genes have been linked to EDMD. Despite rigorous screening, at least 50% of patients with EDMD have no detectable mutation in the 6 known genes.

Now the breakthrough study has discovered two more genes linked to the disease.

Lead researcher at Leicester, Dr Sue Shackleton, senior lecturer in Biochemistry, said:

"We are really excited to have identified mutations in two new genes - SUN1 and SUN2 - that are responsible for causing some cases of the muscle wasting disease Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy.

"Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) is an inherited condition that affects around 1,000 people in the UK. It involves muscle wasting and stiffening of the joints. These symptoms usually begin in early childhood and worsen over time, so that many patients have significantly reduced mobility later in life.

"By adulthood, most individuals also develop heart problems that result in an abnormal heartbeat and a high risk of sudden cardiac arrest – the main treatment for this is insertion of a pacemaker. At the moment there is no cure for this disease and no effective treatment for the muscle wasting and joint stiffening."

Dr Shackleton said that in some individuals, EDMD is caused by mutations in one of several genes that are responsible for producing proteins that form a structural support network, or "scaffold", for each cell's nucleus – the compartment that contains the DNA. The reason why mutations in these genes cause this disease is not fully understood, but one theory proposes that the mutations weaken the scaffold structure, leading to damage and death of muscle cells as they continually contract and relax.

However, in up to 50% of individuals with EDMD, no mutation has been identified in any these genes.

Dr Shackleton said: "Our research has identified two new genes, SUN1 and SUN2, that are responsible for causing EDMD in some of these individuals. The proteins produced by these genes also form part of the structural scaffold of the nucleus.

Importantly, we have identified a novel way in which these mutations act in muscle cells.

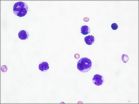

"Our research has shown that the mutated SUN1 and SUN2 proteins interfere with connections between the nucleus and the rest of the cell and that this results in abnormal positioning of the nuclei within the muscle cells. The nuclei are normally anchored at the edges of muscle cells, probably so that they do not get in the way of the main structures of the cell that are involved in muscle contraction. Incorrect positioning could further damage the nuclei and could also impair muscle contraction, leading to the muscle wasting and weakness seen in EDMD sufferers.

"We therefore believe that incorrect positioning of muscle nuclei may contribute to causing the symptoms of EDMD. Further research is now needed to investigate this new potential disease mechanism and to increase our understanding of how nuclei are positioned in normal muscle cells, but our findings offer the possibility for a novel drug target for the treatment of this disease in the future."

Dr Marita Pohlschmidt, Director of Research at the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign, said:

"We welcome the encouraging results of this study, which has identified two new genes which can cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. In the future, this will give more people an accurate genetic diagnosis, helping them to understand the risk of passing it on to their children and to make informed choices with regards to planning for a family.

An accurate genetic diagnosis also means that patients will receive more precise information about the prognosis of the condition. Most importantly, a better understanding of the condition is crucial for the development of treatments for this complex and devastating condition."

Emily Beale, whose son Tayler (11) has Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, said:

"Tayler's condition affects the muscles in his legs, arms and neck. He falls regularly because of the weakness in his calf muscles which causes his feet to droop and general instability in his legs. This year he lost the ability to run, he was never very fast, but he misses the ability to try and keep up. In the last year, Tayler's elbows have started to contract meaning he cannot stretch his arms out straight. He finds carrying heavy objects difficult, and struggles to hold things for long periods of time with his hands.

"We are thrilled that someone is researching Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and we hope that Tayler will see a treatment within his lifetime."

INFORMATION: END

New genetic targets discovered in fight against muscle-wasting disease

Findings offer possibility of developing new ways of tackling incurable condition

2014-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New species of electrons can lead to better computing

2014-09-11

In a research paper published this week in Science, the collaboration led by MIT's theory professor Leonid Levitov and Manchester's Nobel laureate Sir Andre Geim report a material in which electrons move at a controllable angle to applied fields, similar to sailboats driven diagonally to the wind.

The material is graphene – one atom-thick chicken wire made from carbon – but with a difference. It is transformed to a new so-called superlattice state by placing it on top of boron nitride, also known as `white graphite', and then aligning the crystal lattices of the two materials. ...

'Hot Jupiters' provoke their own host suns to wobble

2014-09-11

Blame the "hot Jupiters."

These large, gaseous exoplanets (planets outside our solar system) can make their suns wobble when they wend their way through their own solar systems to snuggle up against their suns, according to new Cornell University research to be published in Science, Sept. 11.

Images: https://cornell.box.com/lai

"Although the planet's mass is only one-thousandth of the mass of the sun, the stars in these other solar systems are being affected by these planets and making the stars themselves act in a crazy way," said Dong Lai, Cornell professor of ...

Diversified farming practices might preserve evolutionary diversity of wildlife

2014-09-11

As humans transform the planet to meet our needs, all sorts of wildlife continue to be pushed aside, including many species that play key roles in Earth's life-support systems. In particular, the transformation of forests into agricultural lands has dramatically reduced biodiversity around the world.

A new study by scientists at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, in this week's issue of Science shows that evolutionarily distinct species suffer most heavily in intensively farmed areas. They also found, however, that an extraordinary amount of evolutionary ...

You can classify words in your sleep

2014-09-11

When people practice simple word classification tasks before nodding off—knowing that a "cat" is an animal or that "flipu" isn't found in the dictionary, for example—their brains will unconsciously continue to make those classifications even in sleep. The findings, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 11, show that some parts of the brain behave similarly whether we are asleep or awake and pave the way for further studies on the processing capacity of our sleeping brains, the researchers say.

"We show that the sleeping brain can be far more ...

Gut microbes determine how well the flu vaccine works

2014-09-11

Annual flu epidemics cause millions of cases of severe illness and up to half a million deaths every year around the world, despite widespread vaccination programs. A study published by Cell Press on September 11th in Immunity reveals that gut microbes play an important role in stimulating protective immune responses to the seasonal flu vaccine in mice, suggesting that differences in the composition of gut microbes in different populations may impact vaccine immunity. The study paves the way for global public health strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine. ...

Stem cells help researchers understand how schizophrenic brains function

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers have gained new insight into what may cause schizophrenia by revealing the altered patterns of neuronal signaling associated with this disease. They did so by exposing neurons derived from the hiPSCs of healthy individuals and of patients with schizophrenia to potassium chloride, which triggered these stem cells to release neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, that are crucial for brain function and are linked to various disorders. By discovering a simple method for stimulating hiPSCs to release neurotransmitters, ...

Intestinal bacteria needed for strong flu vaccine responses in mice

2014-09-11

Mice treated with antibiotics to remove most of their intestinal bacteria or raised under sterile conditions have impaired antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination, researchers have found.

The findings suggest that antibiotic treatment before or during vaccination may impair responses to certain vaccines in humans. The results may also help to explain why immunity induced by some vaccines varies in different parts of the world.

In a study to be published in Immunity, Bali Pulendran, PhD, and colleagues at Emory University demonstrate a dependency on gut ...

Our microbes are a rich source of drugs, UCSF researchers discover

2014-09-11

Bacteria that normally live in and upon us have genetic blueprints that enable them to make thousands of molecules that act like drugs, and some of these molecules might serve as the basis for new human therapeutics, according to UC San Francisco researchers who report their new discoveries in the September 11, 2014 issue of Cell.

The scientists purified and solved the structure of one of the molecules they identified, an antibiotic they named lactocillin, which is made by a common bacterial species, Lactobacillus gasseri, found in the microbial community within the vagina. ...

Cells put off protein production during times of stress

2014-09-11

DURHAM, N.C. -- Living cells are like miniature factories, responsible for the production of more than 25,000 different proteins with very specific 3-D shapes. And just as an overwhelmed assembly line can begin making mistakes, a stressed cell can end up producing misshapen proteins that are unfolded or misfolded.

Now Duke University researchers in North Carolina and Singapore have shown that the cell recognizes the buildup of these misfolded proteins and responds by reshuffling its workload, much like a stressed out employee might temporarily move papers from an overflowing ...

A non-toxic strategy to treat leukemia

2014-09-11

A study comparing how blood stem cells and leukemia cells consume nutrients found that cancer cells are far less tolerant to shifts in their energy supply than their normal counterparts. The results suggest that there could be ways to target leukemia metabolism so that cancer cells die but other cell types are undisturbed.

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine and the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology led the work, published in the journal Cell, in collaboration with ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] New genetic targets discovered in fight against muscle-wasting diseaseFindings offer possibility of developing new ways of tackling incurable condition