(Press-News.org) Imagine a balloon that could float without using any lighter-than-air gas. Instead, it could simply have all of its air sucked out while maintaining its filled shape. Such a vacuum balloon, which could help ease the world's current shortage of helium, can only be made if a new material existed that was strong enough to sustain the pressure generated by forcing out all that air while still being lightweight and flexible.

Caltech materials scientist Julia Greer and her colleagues are on the path to developing such a material and many others that possess unheard-of combinations of properties. For example, they might create a material that is thermally insulating but also extremely lightweight, or one that is simultaneously strong, lightweight, and nonbreakable—properties that are generally thought to be mutually exclusive.

Greer's team has developed a method for constructing new structural materials by taking advantage of the unusual properties that solids can have at the nanometer scale, where features are measured in billionths of meters. In a paper published in the September 12 issue of the journal Science, the Caltech researchers explain how they used the method to produce a ceramic (e.g., a piece of chalk or a brick) that contains about 99.9 percent air yet is incredibly strong, and that can recover its original shape after being smashed by more than 50 percent.

"Ceramics have always been thought to be heavy and brittle," says Greer, a professor of materials science and mechanics in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science at Caltech. "We're showing that in fact, they don't have to be either. This very clearly demonstrates that if you use the concept of the nanoscale to create structures and then use those nanostructures like LEGO to construct larger materials, you can obtain nearly any set of properties you want. You can create materials by design."

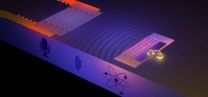

The researchers use a direct laser writing method called two-photon lithography to "write" a three-dimensional pattern in a polymer by allowing a laser beam to crosslink and harden the polymer wherever it is focused. The parts of the polymer that were exposed to the laser remain intact while the rest is dissolved away, revealing a three-dimensional scaffold. That structure can then be coated with a thin layer of just about any kind of material—a metal, an alloy, a glass, a semiconductor, etc. Then the researchers use another method to etch out the polymer from within the structure, leaving a hollow architecture.

The applications of this technique are practically limitless, Greer says. Since pretty much any material can be deposited on the scaffolds, the method could be particularly useful for applications in optics, energy efficiency, and biomedicine. For example, it could be used to reproduce complex structures such as bone, producing a scaffold out of biocompatible materials on which cells could proliferate.

In the latest work, Greer and her students used the technique to produce what they call three-dimensional nanolattices that are formed by a repeating nanoscale pattern. After the patterning step, they coated the polymer scaffold with a ceramic called alumina (i.e., aluminum oxide), producing hollow-tube alumina structures with walls ranging in thickness from 5 to 60 nanometers and tubes from 450 to 1,380 nanometers in diameter.

Greer's team next wanted to test the mechanical properties of the various nanolattices they created. Using two different devices for poking and prodding materials on the nanoscale, they squished, stretched, and otherwise tried to deform the samples to see how they held up.

They found that the alumina structures with a wall thickness of 50 nanometers and a tube diameter of about 1 micron shattered when compressed. That was not surprising given that ceramics, especially those that are porous, are brittle. However, compressing lattices with a lower ratio of wall thickness to tube diameter—where the wall thickness was only 10 nanometers—produced a very different result.

"You deform it, and all of a sudden, it springs back," Greer says. "In some cases, we were able to deform these samples by as much as 85 percent, and they could still recover."

To understand why, consider that most brittle materials such as ceramics, silicon, and glass shatter because they are filled with flaws—imperfections such as small voids and inclusions. The more perfect the material, the less likely you are to find a weak spot where it will fail. Therefore, the researchers hypothesize, when you reduce these structures down to the point where individual walls are only 10 nanometers thick, both the number of flaws and the size of any flaws are kept to a minimum, making the whole structure much less likely to fail.

"One of the benefits of using nanolattices is that you significantly improve the quality of the material because you're using such small dimensions," Greer says. "It's basically as close to an ideal material as you can get, and you get the added benefit of needing only a very small amount of material in making them."

The Greer lab is now aggressively pursuing various ways of scaling up the production of these so-called meta-materials.

INFORMATION:

The lead author on the paper, "Strong, Lightweight and Recoverable Three-Dimensional Ceramic Nanolattices," is Lucas R. Meza, a graduate student in Greer's lab. Satyajit Das, who was a visiting student researcher at Caltech, is also a coauthor. The work was supported by funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies. Greer is also on the board of directors of the Kavli Nanoscience Institute at Caltech.

Ceramics don't have to be brittle

Caltech materials scientists are creating materials by design

2014-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists report first semiaquatic dinosaur, Spinosaurus

2014-09-11

WASHINGTON (Sept. 11, 2014)—Scientists today unveiled what appears to be the first truly semiaquatic dinosaur, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. New fossils of the massive Cretaceous-era predator reveal it adapted to life in the water some 95 million years ago, providing the most compelling evidence to date of a dinosaur able to live and hunt in an aquatic environment. The fossils also indicate that Spinosaurus was the largest known predatory dinosaur to roam the Earth, measuring more than 9 feet longer than the world's largest Tyrannosaurus rex specimen. These findings, published ...

Malaria parasites sense and react to mosquito presence to increase transmission

2014-09-11

Many pathogens are transmitted by insect bites. The abundance of vectors (as the transmitting insects are called) depends on seasonal and other environmental fluctuations. An article published on September 11thin PLOS Pathogens demonstrates that Plasmodium parasites react to mosquitoes biting their hosts, and that the parasite responses increase transmission to the mosquito vector.

Sylvain Gandon, from the CNRS in Montpellier, France, and colleagues first studied the theoretical evolution of parasite evolution in a variable environment. Using a mathematical model, they ...

Evolutionary tools improve prospects for sustainable development

2014-09-11

Solving societal challenges in food security, emerging diseases and biodiversity loss will require evolutionary thinking in order to be effective in the long run. Inattention to this will only lead to greater challenges such as short-lived medicines and agricultural treatments, problems that may ultimately hinder sustainable development, argues a new study published online today in Science Express, led by University of California, Davis and the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen.

For the first time, scientists have reviewed ...

Dartmouth study may shed light on molecular mechanisms of birth defects among older women

2014-09-11

Dartmouth researchers studying cell division in fruit flies have discovered a pathway that may improve understanding of molecular mistakes that cause older women to have babies with Down syndrome.

The study shows for the first time that new protein linkages occur in immature egg cells after DNA replication and that these replacement linkages are essential for these cells to maintain meiotic cohesion for long periods.

The study appears in the journal PLOS Genetics. A PDF is available on request.

As women age, so do their eggs and during a woman's thirties, the chance ...

The sound of an atom has been captured

2014-09-11

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology are first to show the use of sound to communicate with an artificial atom. They can thereby demonstrate phenomena from quantum physics with sound taking on the role of light. The results will be published in the journal Science.

The interaction between atoms and light is well known and has been studied extensively in the field of quantum optics. However, to achieve the same kind of interaction with sound waves has been a more challenging undertaking. The Chalmers researchers have now succeeded in making acoustic waves couple ...

New genetic targets discovered in fight against muscle-wasting disease

2014-09-11

Scientists have pinpointed for the first time the genetic cause in some people of an incurable muscle-wasting disease, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD).

The international research team led by the University of Leicester say the finding of two target genes opens the possibility of developing drugs to tackle the disease in these patients. Their work has been published today in the journal PLOS Genetics.

The research was funded by The Wellcome Trust and was only possible by the University of Leicester team collaborating with groups in Germany (University of Greifswald), ...

New species of electrons can lead to better computing

2014-09-11

In a research paper published this week in Science, the collaboration led by MIT's theory professor Leonid Levitov and Manchester's Nobel laureate Sir Andre Geim report a material in which electrons move at a controllable angle to applied fields, similar to sailboats driven diagonally to the wind.

The material is graphene – one atom-thick chicken wire made from carbon – but with a difference. It is transformed to a new so-called superlattice state by placing it on top of boron nitride, also known as `white graphite', and then aligning the crystal lattices of the two materials. ...

'Hot Jupiters' provoke their own host suns to wobble

2014-09-11

Blame the "hot Jupiters."

These large, gaseous exoplanets (planets outside our solar system) can make their suns wobble when they wend their way through their own solar systems to snuggle up against their suns, according to new Cornell University research to be published in Science, Sept. 11.

Images: https://cornell.box.com/lai

"Although the planet's mass is only one-thousandth of the mass of the sun, the stars in these other solar systems are being affected by these planets and making the stars themselves act in a crazy way," said Dong Lai, Cornell professor of ...

Diversified farming practices might preserve evolutionary diversity of wildlife

2014-09-11

As humans transform the planet to meet our needs, all sorts of wildlife continue to be pushed aside, including many species that play key roles in Earth's life-support systems. In particular, the transformation of forests into agricultural lands has dramatically reduced biodiversity around the world.

A new study by scientists at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, in this week's issue of Science shows that evolutionarily distinct species suffer most heavily in intensively farmed areas. They also found, however, that an extraordinary amount of evolutionary ...

You can classify words in your sleep

2014-09-11

When people practice simple word classification tasks before nodding off—knowing that a "cat" is an animal or that "flipu" isn't found in the dictionary, for example—their brains will unconsciously continue to make those classifications even in sleep. The findings, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 11, show that some parts of the brain behave similarly whether we are asleep or awake and pave the way for further studies on the processing capacity of our sleeping brains, the researchers say.

"We show that the sleeping brain can be far more ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] Ceramics don't have to be brittleCaltech materials scientists are creating materials by design