(Press-News.org) Where are the quantum computers? Aren't they supposed to be speeding up decryption and internet searches? After two decades of research, you still can't find them in stores. Well, it took two decades or more of research dedicated to semiconductors and circuit integration before we had digital computers. For quantum computers too it will take technology more time to catch up to the science

Meanwhile, research devoted to exploring bizarre quantum phenomena must continue to overcome or reduce a litany of practical obstacles before quantum computing can be realized. Not the least of these obstacles remains the isolation of qubits---the repository of quantum information---from their surroundings. A qubit, or better yet an ensemble of qubits, exists in a superposition of two or more possible states. The trouble is that superposition is a fragile condition, and the manipulation and final readout of those states are in danger of being undone if a qubit interacts with its environment. A new paper, published in Nature Physics (1) addresses this problem by demonstrating a new type of qubit control, one that actually makes productive use of a qubit's proximity to its surroundings.

The experimental work was performed at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University in the UK. JQI (2) scientist Jacob Taylor provided the theoretical input to the work over the course of five years of cross-Atlantic collaboration.

ENVIRONMENTAL-ASSISTED CONTROL

Qubits come in many forms but have one essential thing in common: they all embody a physical system---whether in the form of a photon or atom or electron or electrical current---which exists in two quantum states simultaneously. In the Cambridge experiment the qubit is a single electron trapped in a semiconductor. The two quantum states, in this case, consist of the two orientations for the electron's tiny spin, either up or down.

The electron's trap is a tiny region of the semiconductor called a quantum dot, essentially a zero-dimensional volume housing a single active electron. When studied at a temperature of about 4 K, the electron spreads as a wave across the 10 nanometer length of the quantum dot. The dot can be considered to be an artificial atom in which the electron (instead of orbiting a single nucleus) is confined in the crystalline lattice of millions of atoms. And like electrons in regular atoms, the select electron in a quantum dot possesses an energy spectrum of discrete energies.

The dot is fabricated using existing nanotechology. In substance it is a tiny lump of indium arsenide (InAs) grown amidst surrounding thicker layers of gallium arsenide (GaAs). Recall the story of the princess and the pea; a girl confirms her status as a princess by detecting a very faint lumpiness created by the presence of a single pea sandwiched between much larger mattresses.

Here the pea is the InAs quantum dot and the mattresses are the GaAs layers. The two species of semiconductor blend, InAs and GaAs, are incommensurate, meaning that their natural atomic spacings are slightly different. In practice this ensures that the atoms in the InAs dot are under some stress amid the surrounding GaAs atom layers. This stress, in turn, leads to the growth of such small 'pea'-like dots, confining the electron inside. Fortunately, one can probe the properties of these buried quantum dots via light, as the materials are transparent, allowing experimentalists to control and manipulate the electron using lasers.

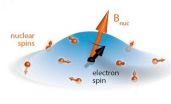

The electron's energy spectrum is made still more complicated by the faint magnetic interaction between it and the nuclei of all those indium and arsenic atoms. Each of those nuclei has a net magnetic field and behaves as if it were a tiny magnet. Those nuclei, in the absence of an external magnetic field, are pointing in all different directions. But at any one moment, the totality of the nuclei exert a single, effective field, which the electron senses. The collective nuclei form a magnetic "environment" for the electron. In just a moment we'll see how the electron is employed as a qubit and how its environment---usually viewed as a threat to maintaining the quantum integrity of the qubit---is actually put to use in the process of manipulating and reading out the qubit.

QUANTUM DARK STATES

If a laser strikes the quantum dot at certain wavelengths corresponding to allowed electron energies, the dot will absorb and then reemit light. It will fluoresce. Things get more interesting, however, if the electron can be coaxed into not absorbing light. To do this a dark state must be created.

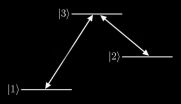

Generally, if a laser beam is tuned to the energy difference between two quantum levels, the atom can absorb laser light and be promoted to the more excited of the two states. The continued presence of the laser light will later stimulate the atom to re-emit the light and return to its lower (ground) state. In some circumstances this absorption/emission process can be stymied if there are closely spaced ground states.

Two laser beams, one tuned to promote the atom from state 1 to state 3 and one tuned to promote the atom from state 2 to state 3, can interfere with each other, leaving state 3 unreachable. This destructive interference can be turned on and off by changing the relative phase of the two laser beams.

This method is employed in the Cambridge experiment. The quantum dot qubit consists of the lone electron being maintained in a state of superposition (spin up and spin down) by laser light. Moreover, the presence of the underlying nuclear magnetic field forming the electron's "environment" helps establish a two-part ground state. Thereafter, the combination of the environment, plus the presence of two carefully-tuned laser beams allows the state of the qubit to be controlled (swiveled around in space) and even to be read out when detectors glimpse the electron as a bright (fluorescent) or a dark object.

In quantum computing, the explicit state of the qubit is unknown (spin up or spin down); this is positively a necessary condition---a required indeterminacy---for the quantum computation to continue. The only thing required is that one knows the relative change in the qubit, such as whether it was swiveled through an angle of 90 or 180 degrees. In conventional computing an example would be a NOT gate, which changes a bit from a 1 state into a 0 state or vice versa. It's only important to know the relative change in the bit, not its actual value. "What is profound is that the electron spin is always in the same quantum superposition, but the physical state evolves with the nuclear field," notes Mete Atature, the Cambridge researcher leading the experimental study.

"Usually you need an external magnetic field to manipulate qubits," says Jacob Taylor, "but this single field can't be used also to read out the final state of a qubit. In our all-optical approach we don't use a field so we can perform manipulation and readout with a single setup."

INFORMATION:

1. "Environment-assisted quantum control of a solid-state spin via coherent dark states,"

Jack Hansom, Carsten H. H. Schulte, Claire Le Gall, Clemens Matthiesen, Edmund Clarke, Maxime Hugues, Jacob M. Taylor, Mete Atatüre, Nature Physics, Nature Physics 10, 725–730 (2014),

doi:10.1038/nphys3077; published online 7 September 2014

2. The Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) is operated by the National Institute for Standards and Technology and the University of Maryland (http://jqi.umd.edu/)

3. Previous press release about 3-electron quantum dot qubits: http://jqi.umd.edu/news/resonant-exchange-qubits.

4. Previous press release about reducing noise in quantum-dot qubits: http://jqi.umd.edu/news/reducing-noise-qubit-arrays

5. Previous press release about Bloch spheres and how to manipulate qubits: http://jqi.umd.edu/news/quantum-longitude

Jacob Taylor, jmtaylor@umd.edu

Press contact at JQI: Phillip F. Schewe, pschewe@umd.edu, 301-405-0989. http://jqi.umd.edu/

Montréal, October 2, 2014 – Scientists at the IRCM discovered a mechanism that promotes the progression of medulloblastoma, the most common brain tumour found in children. The team, led by Frédéric Charron, PhD, found that a protein known as Sonic Hedgehog induces DNA damage, which causes the cancer to develop. This important breakthrough will be published in the October 13 issue of the prestigious scientific journal Developmental Cell. The editors also selected the article to be featured on the journal's cover.

Sonic Hedgehog belongs to a family of proteins that gives ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The big-headed ant (Pheidole megacephala) is considered one of the world's worst invasive ant species. As the name implies, its colonies include soldier ants with disproportionately large heads. Their giant, muscle-bound noggins power their biting parts, the mandibles, which they use to attack other ants and cut up prey. In a new study, researchers report that big-headed ant colonies produce larger soldiers when they encounter other ants that know how to fight back.

The new findings appear in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Big-headed ...

London, United Kingdom, October 2, 2014 – Despite decades of research, scientists have yet to pinpoint the exact cause of nodding syndrome (NS), a disabling disease affecting African children. A new report suggests that blackflies infected with the parasite Onchocerca volvulus may be capable of passing on a secondary pathogen that is to blame for the spread of the disease. New research is presented in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Concentrated in South Sudan, Northern Uganda, and Tanzania, NS is a debilitating and deadly disease that affects young ...

A new study published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on October 2 could rewrite the story of ape and human brain evolution. While the neocortex of the brain has been called "the crowning achievement of evolution and the biological substrate of human mental prowess," newly reported evolutionary rate comparisons show that the cerebellum expanded up to six times faster than anticipated throughout the evolution of apes, including humans.

The findings suggest that technical intelligence was likely at least as important as social intelligence in human cognitive ...

The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions.

"Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation—curiosity—affects memory. These findings ...

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that AIM (Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage), a protein that plays a preventive role in obesity progression, can also prevent tumor development in mice liver cells. This discovery may lead to a therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths.

Professor Toru Miyazaki's group at the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine from Pathogenesis, in the Faculty of Medicine has shown that AIM (also known ...

LA JOLLA, CA—October 2, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that an enzyme best known for its fundamental role in building proteins has a second major function: to protect DNA during times of cellular stress.

The finding is remarkable on a basic science level but also points the way to possible therapeutic applications. Strategies that enhance the DNA-protection function of the enzyme, TyrRS, could help protect people from radiation injuries as well as from hereditary defects in DNA repair systems.

"We overexpressed TyrRS in zebrafish ...

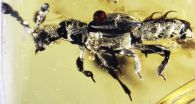

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a 52-million-year old beetle that likely was able to live alongside ants—preying on their eggs and usurping resources—within the comfort of their nest. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from India, is the oldest-known example of this kind of social parasitism, known as "myrmecophily." Published today in the journal Current Biology, the research also shows that the diversification of these stealth beetles, which infiltrate ant nests around the world today, correlates with the ecological rise of modern ants.

"Although ants ...

Our immune system must distinguish between self and foreign and in order to fight infections without damaging the body's own cells at the same time. The immune system is loyal to cells in the body, but how this works is not fully understood. Researchers in the Departments of Biomedicine and Nephrology at the University Hospital and the University of Basel have discovered that the immune system uses a molecular biological clock to target intolerant T cells during their maturation process. These recent findings have been reported in the scientific journal Cell.

A functioning ...

It's an early lesson in genetics: we get half our DNA from Mom, half from Dad.

But that straightforward explanation does not account for a process that sometimes occurs when cells divide. Called gene conversion, the copy of a gene from Mom can replace the one from Dad, or vice versa, making the two copies identical.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers Joseph Lachance and Sarah A. Tishkoff investigated this process in the context of the evolution of human populations. They found that a bias toward ...