(Press-News.org) Scientists from the University of Leeds have taken a crucial step forward in bio-nanotechnology, a field that uses biology to develop new tools for science, technology and medicine.

The new study, published in print today in the journal Nano Letters, demonstrates how stable 'lipid membranes' – the thin 'skin' that surrounds all biological cells – can be applied to synthetic surfaces.

Importantly, the new technique can use these lipid membranes to 'draw' – akin to using them like a biological ink – with a resolution of 6 nanometres (6 billionths of a meter), which is much smaller than scientists had previously thought was possible.

"This is smaller than the active elements of the most advanced silicon chips and promises the ability to position functional biological molecules – such as those involved in taste, smell, and other sensory roles – with high precision, to create novel hybrid bio-electronic devices," said Professor Steve Evans, from the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leeds and a co-author of the paper.

In the study, the researchers used something called Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), which is an imaging process that has a resolution down to only a fraction of a nanometer and works by scanning an object with a miniscule mechanical probe. AFM, however, is more than just an imaging tool and can be used to manipulate materials in order to create nanostructures and to 'draw' substances onto nano-sized regions. The latter is called 'nano-lithography' and was the technique used by Professor Evans and his team in this research.

The ability to controllably 'write' and 'position' lipid membrane fragments with such high precision was achieved by Mr George Heath, a PhD student from the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leeds and the lead author of the research paper.

Mr Heath said: "The method is much like the inking of a pen. However, instead of writing with fluid ink, we allow the lipid molecules – the ink – to dry on the tip first. This allows us to then write underwater, which is the natural environment for lipid membranes. Previously, other research teams have focused on writing with lipids in air and they have only been able to achieve a resolution of microns, which is a thousand times larger than what we have demonstrated."

The research is of fundamental importance in helping scientists understand the structure of proteins that are found in lipid membranes, which are called 'membrane proteins'. These proteins act to control what can be let into our cells, to remove unwanted materials, and a variety of other important functions.

For example, we smell things because of membrane proteins called 'olfactory receptors', which convert the detection of small molecules into electrical signals to stimulate our sense of smell. And many drugs work by targeting specific membrane proteins.

"Currently, scientists only know the structure of a small handful of membrane proteins. Our research paves the way to understand the structure of the thousands of different types of membrane proteins to allow the development of many new drugs and to aid our understanding of a range of diseases," explained Professor Evans.

Aside from biological applications, this area of research could revolutionise renewable energy production.

Working in collaboration with researchers at the University of Sheffield, Professor Evans and his team have all of the membrane proteins required to construct a fully working mimic of the way plants capture sunlight. Eventually, the researchers will be able to arbitrarily swap out the biological units and replace them with synthetic components to create a new generation of solar cells.

Professor Evans concludes: "This is part of the emerging field of synthetic biology, whereby engineering principles are being applied to biological parts – whether it is for energy capture, or to create artificial noses for the early detection of disease or simply to advise you that the milk in your fridge has gone off.

"The possibilities are endless."

INFORMATION:

Further information

The research paper, 'Diffusion in Low-Dimensional Lipid Membranes', is published on 8 October 2014 in the journal Nano Letters.

This research was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

George Heath and Professor Steve Evans are available for interview. Please contact University of Leeds press office on pressoffice@leeds.ac.uk or call +44 (0)113 34 34196

Image Caption: Mr George Heath setting up the Atomic Force Microscope, which sits on a vibration isolation table and is held within an acoustic hood to isolate external noise.

Credit: Mr George Heath

Image download: http://goo.gl/jb677k

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. http://www.leeds.ac.uk

Smallest world record has 'endless possibilities' for bio-nanotechnology

2014-10-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Antarctic sea ice reaches new record maximum

2014-10-08

VIDEO:

The Arctic and the Antarctic are regions that have a lot of ice and acts as air conditioners for the Earth system. This year, Antarctic sea ice reached a record...

Click here for more information.

Sea ice surrounding Antarctica reached a new record high extent this year, covering more of the southern oceans than it has since scientists began a long-term satellite record to map sea ice extent in the late 1970s. The upward trend in the Antarctic, however, is only about ...

Neurons in human muscles emphasize the impact of the outside world

2014-10-08

Stretch sensors in our muscles participate in reflexes that serve the subconscious control of posture and movement. According to a new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, these sensors respond weakly to muscle stretch caused by one's voluntary action, and most strongly to stretch that is imposed by external forces. The ability to reflect causality in this manner can facilitate appropriate reflex control and accurate self-perception.

"The results of the study show that stretch receptors in our muscles indicate more than which limb is moving or how fast; these ...

Treasure trove of ancient genomes helps recalibrate the human evolutionary clock

2014-10-08

Just like adjusting a watch, the key to accurately telling evolutionary time is based upon periodically calibrating against a gold standard.

Scientists have long used DNA data to develop molecular clocks that measure the rate at which DNA changes, i.e., accumulates mutations, as a premiere tool to peer into the past evolutionary timelines for the lineage of a given species. In human evolution, for example, molecular clocks, when combined with fossil evidence, have helped trace the time of the last common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans to 5-7 million years ago, and ...

Gluing chromosomes at the right place

2014-10-08

During cell division, chromosomes acquire a characteristic X-shape with the two DNA molecules (sister chromatids) linked at a central "connection region" that contains highly compacted DNA. It was unknown if rearrangements in this typical X-shape architecture could disrupt the correct separation of chromosomes. A recent study by Raquel Oliveira, from the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (Portugal), in collaboration with colleagues from the University of California, Santa Cruz (USA), now shows that the dislocation of particular DNA segments perturbs proper chromosome ...

Fine-tuning of bitter taste receptors may be key to animal survival

2014-10-08

One key to animal survival is bitter taste----the better to avoid ingesting potentially harmful poisons or foods. The evolution of bitter taste has been a hot topic amongst evolutionary biologists, and with more and more DNA data available, a rich area of exploration.

Now, professor Maik Behrens, et. al. examined the genetic repertoire of bitter taste receptor genes in chickens and frogs, which represent two extremes. Chickens only have 3 bitter taste receptor genes (Tas2rs), while frogs have more than 50 (humans are somewhere in the middle). They studied the different ...

Dietary fat under fire

2014-10-08

This news release is available in French. The association between saturated fat and cardiovascular risk has become a hot topic in nutrition. Researchers at the Institute of nutrition and functional foods (INAF) of Université Laval are calling for a review of dietary recommendations on saturated fat (SFA) in relation to cardiovascular disease (CVD).

In a Comment paper, published today in the journal Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism the authors provide a number of arguments for the urgency to re-assess the association between dietary saturated fat ...

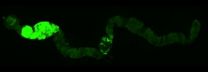

Flies with colon cancer help to unravel the genetic keys to disease in humans

2014-10-08

Researchers at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) have managed to generate a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) model that reproduces human colon cancer. With two publications appearing in PLoS One and EMBO Reports, the IRB team also unveil the function of a key gene in the development of the disease.

"The breakthrough is that we have generated cancer in an adult organism and from stem cells, thus reproducing what happens in most types of human cancer. This model has allowed us to identify subtle interactions in the development of cancer that are ...

Fruit flies reveal features of human intestinal cancer

2014-10-08

HEIDELBERG, 8 October 2014 – Researchers in Spain have determined how a transcription factor known as Mirror regulates tumour-like growth in the intestines of fruit flies. The scientists believe a related system may be at work in humans during the progression of colorectal cancer due to the observation of similar genes and genetic interactions in cultured colorectal cancer cells. The results are reported in the journal EMBO Reports.

Colorectal cancer leads to more than half a million deaths worldwide each year. The disease originates in the epithelial cells of the ...

Supervisors' abuse, regardless of intent, can make employees behave poorly

2014-10-08

SAN FRANCISCO, Oct. 8, 2014 -- Employees who are verbally abused by supervisors are more likely to "act out" at work, doing everything from taking a too-long lunch break to stealing, according to a new study led by a San Francisco State University organizational psychologist.

Even if the abuse is meant to be motivational -- like when a football coach berates his team or a drill sergeant shames her cadets -- the abused employees are still more likely to engage in counter-productive work behaviors, said Kevin Eschleman, assistant professor of psychology at SF State.

The ...

Large chain restaurants appear to be voluntarily reducing calories in their menu items

2014-10-08

New research from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health finds that large chain restaurants, whose core menu offerings are generally high in calories, fat and sodium, introduced newer food and beverage options that, on average, contain 60 fewer calories than their traditional menu selections in 2012 and 2013.

Researchers say this could herald a trend in calorie reduction in anticipation of expected new federal government rules requiring large chain restaurants – including most fast-food places – to post calorie counts on their menus. The appearance ...