A decade of refinements in transplantation improves long-term survival of blood cancers

2010-11-25

(Press-News.org) SEATTLE – A decade of refinements in marrow and stem cell transplantation to treat blood cancers significantly reduced the risk of treatment-related complications and death, according to an institutional self-analysis of transplant-patient outcomes conducted at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

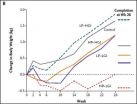

Among the major findings of the study, which compared transplant-patient outcomes in the mid-'90s with those a decade later: After adjusting for factors known to be associated with outcome, the researchers observed a statistically significant 60 percent reduction in the risk of death within 200 days of transplant and a 41 percent reduction in the risk of overall mortality at any time after transplant.

"Everything we looked at improved a decade after the initial analysis," said George McDonald, M.D., a Hutchinson Center gastroenterologist and corresponding author of the paper, which was published (date) in the New England Journal of Medicine.

McDonald and colleagues reviewed the outcomes of 1,418 transplant patients who received peripheral-blood stem cells or bone marrow from unrelated donors between 1993 and 1997 and compared them to 1,148 patients who had the same procedures between 2003 and 2007. The malignancies treated included forms of leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma and myelodysplastic syndrome.

The researchers also found that the estimated one-year overall survival rates for both groups were 55 percent and 70 percent, respectively. They also observed statistically significant declines in the risks of severe graft-vs-host-disease; infections caused by viruses, bacteria and fungi; and complications caused by damage to the lungs, kidney and liver.

Lead author and biostatistician Ted Gooley, Ph.D., noted that the analysis presents the findings in terms of the changes in the "risk" or "hazard" of death and transplant complications after taking into account the fact that the patients treated in the mid-2000s were, on average, older and sicker than those who were treated in the mid-1990s.

McDonald said he and his colleagues can only speculate about the reasons for the improved outcomes because the study was retrospective and was not a randomized comparison of transplant techniques and treatments among groups of patients. However, the authors deemed several changes in clinical practices to be important in risk reduction, many of which were the result of ongoing clinical research (including various randomized clinical trials) conducted at the Hutchinson Center and at other major transplant centers around the world:

Careful pharmacologic monitoring and dose adjustments to avoid under and over treatment with the potent chemotherapeutic agents used in transplantation.

Use of reduced-intensity conditioning in older and less healthy patients.

Less use of high-dose systemic immune suppression to treat acute GVHD.

Use of the drug ursodiol to prevent liver complications.

New methods for early detection of viral and fungal infections as well as preventive therapy for such infections.

The use of better and less toxic anti-fungal drugs to treat serious infections caused by Candidal organisms and molds.

Use of donor peripheral blood hematopoietic cells instead of bone marrow as the source of donor cells, which results in faster engraftment and return of immunity.

More accurate matching of marrow or stem cell donors with unrelated patients.

"This research and the improved outcomes are the result of a team approach to one of the most complex procedures in medicine," McDonald said. Medical oncologists and transplantation biologists at the Hutchinson Center are supported in the care of patients by specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonary and critical care medicine, nephrology, gastroenterology and hepatology, and by highly skilled nurses and support staff.

"Each of these programs is involved in ongoing clinical research into the complications of transplant, which results in constant changes in how transplantation is carried out," he said. "These data show clearly that our collective efforts have improved the chances of long-term survival for our patients."

### The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

At Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, our interdisciplinary teams of world-renowned scientists and humanitarians work together to prevent, diagnose and treat cancer, HIV/AIDS and other diseases. Our researchers, including three Nobel laureates, bring a relentless pursuit and passion for health, knowledge and hope to their work and to the world. For more information, please visit fhcrc.org.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2010-11-25

STANFORD, Calif. — Despite concerted efforts, no decreases in patient harm were detected at 10 randomly selected North Carolina hospitals between 2002 and 2007, according to a new study from the Stanford University School of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Since a 1999 Institute of Medicine report sounded the alarm about high medical error rates, most U.S. hospitals have changed their operations to keep patients safer. The researchers wanted to assess whether these patient-safety efforts reduced harm. They studied hospitals ...

2010-11-25

The new results, from a team led by Grzegorz Pietrzyński (Universidad de Concepción, Chile, Obserwatorium Astronomiczne Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Poland), appear in the 25 November 2010 edition of the journal Nature.

Grzegorz Pietrzyński introduces this remarkable result: "By using the HARPS instrument on the 3.6-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile, along with other telescopes, we have measured the mass of a Cepheid with an accuracy far greater than any earlier estimates. This new result allows us to immediately see which of the two competing ...

2010-11-25

By cooling Rubidium atoms deeply and concentrating a sufficient number of them in a compact space, they suddenly become indistinguishable. They behave like a single huge "super particle." Physicists call this a Bose-Einstein condensate.

For "light particles," or photons, this should also work. Unfortunately, this idea faces a fundamental problem. When photons are "cooled down," they disappear. Until a few months ago, it seemed impossible to cool light while concentrating it at the same time. The Bonn physicists Jan Klärs, Julian Schmitt, Dr. Frank Vewinger, and Professor ...

2010-11-25

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. -- Researchers at Tufts University School of Engineering have reported the first successful production of the antibiotic erythromycin A, and two variations, using E. coli as the production host.

The work, published in the November 24, 2010, issue of Chemistry and Biology, offers a more cost-effective way to make both erythromycin A and new drugs that will combat the growing incidence of antibiotic resistant pathogens. Equally important, the E. coli production platform offers numerous next-generation engineering opportunities for other natural ...

2010-11-25

Palo Alto, CA— Infestation by bacteria and other pathogens result in global crop losses of over $500 billion annually. A research team led by the Carnegie Institution's Department of Plant Biology developed a novel trick for identifying how pathogens hijack plant nutrients to take over the organism. They discovered a novel family of pores that transport sugar out of the plant. Bacteria and fungi hijack the pores to access the plant sugar for food. The first goal of any pathogen is to access the host's food supply to allow them to reproduce in large numbers. This is the ...

2010-11-25

Researchers with UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have found that melanoma patients whose cancers are caused by mutation of the BRAF gene become resistant to a promising targeted treatment through another genetic mutation or the overexpression of a cell surface protein, both driving survival of the cancer and accounting for relapse.

The study, published Nov. 24, 2010, in the early online edition of the peer-reviewed journal Nature, could result in the development of new targeted therapies to fight resistance once the patient stops responding and the cancer ...

2010-11-25

The past year has brought to light both the promise and the frustration of developing new drugs to treat melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. Early clinical tests of a candidate drug aimed at a crucial cancer-causing gene revealed impressive results in patients whose cancers resisted all currently available treatments. Unfortunately, those effects proved short-lived, as the tumors invariably returned a few months later, able to withstand the same drug to which they first succumbed. Adding to the disappointment, the reasons behind these relapses were unclear.

Now, ...

2010-11-25

Researchers appear to have an explanation for a longstanding question in HIV biology: how it is that the virus kills so many CD4 T cells, despite the fact that most of them appear to be "bystander" cells that are themselves not productively infected. That loss of CD4 T cells marks the progression from HIV infection to full-blown AIDS, explain the researchers who report their findings in studies of human tonsils and spleens in the November 24th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication.

"In [infected] primary human tonsils and spleens, there is a profound depletion of CD4 ...

2010-11-25

Researchers at the Faculty of Life Sciences (LIFE), University of Copenhagen, can now unveil the results of the world's largest diet study:

If you want to lose weight, you should maintain a diet that is high in proteins with more lean meat, low-fat dairy products and beans and fewer finely refined starch calories such as white bread and white rice. With this diet, you can also eat until you are full without counting calories and without gaining weight. Finally, the extensive study concludes that the official dietary recommendations are not sufficient for preventing obesity. ...

2010-11-25

They are the largest fish species in the ocean, but the majestic gliding motion of the whale shark is, scientists argue, an astonishing feat of mathematics and energy conservation. In new research published today in the British Ecological Society's journal Functional Ecology marine scientists reveal how these massive sharks use geometry to enhance their natural negative buoyancy and stay afloat.

For most animals movement is crucial for survival, both for finding food and for evading predators. However, movement costs substantial amounts of energy and while this is true ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A decade of refinements in transplantation improves long-term survival of blood cancers