(Press-News.org) In multiple sclerosis, the immune system goes rogue, improperly attacking the body's own central nervous system. Mobility problems and cognitive impairments may arise as the nerve cells become damaged.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and co-investigators have identified a key protein that is able to reduce the severity of a disease equivalent to MS in mice. This molecule, Del-1, is the same regulatory protein that has been found to prevent inflammation and bone loss in a mouse model of gum disease.

"We see that two completely different disease entities share a common pathogenic mechanism," said George Hajishengallis, a professor of microbiology in Penn's School of Dental Medicine and an author on the study. "And in this case that means that they can even share therapeutic targets, namely Del-1."

Because Del-1 has been found to be associated with susceptibility to not only multiple sclerosis, but also Alzheimer's, it's possible that a properly functioning version of this protein might help guard again that disease's effects as well.

Penn contributors to the study included Hajishengallis, Penn Dental Medicine postdoctoral researcher Kavita Hosur and Khalil Bdeir, a research associate professor at Penn's Perelman School of Medicine. They collaborated with senior author Triantafyllos Chavakis of Germany's Technical University Dresden and researchers from South Korea's University of Ulsan College of Medicine and other institutions. The work appears online in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

In earlier studies, Hajishengallis, Chavakis and colleagues found that Del-1 acts as a gatekeeper that thwarts the movement and accumulation of immune cells like neutrophils, reducing inflammation. While neutrophils are needed to effectively respond to infection or injury, when too many of them accumulate in a tissue, the resulting inflammation can itself be damaging.

Hajishengallis has found that gum tissue affected by periodontitis, a severe form of gum disease associated with inflammation and bone loss-- had lower levels of Del-1 than healthy tissue. Administering Del-1 directly to the gums protected against these effects.

While researching Del-1 in other tissues, such as gums and lungs, Hajishengallis and Chavakis found that Del-1 was also highly expressed in the brain. In addition, genome-wide screens indicate that the Del-1 gene may contribute to multiple sclerosis risk. For these reasons, the scientists hypothesized that Del-1 might prevent inflammation in the central nervous system just as it does in the gum tissue.

To test their theory, the researchers examined Del-1 expression in brain tissue from people who had died from MS. In MS patients with chronic active MS lesions, Del-1 was reduced compared to both healthy brain tissue and brain tissue from MS patients who were in remission at the time of their death. Similarly, Del-1 expression was reduced in the spinal cords of mice with the rodent equivalent of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).

Having confirmed this association between reduced Del-1 and MS and EAE, the scientists wanted to see if the reduction itself played a causal role in the disease.

Hajishengallis's and Chavakis's labs had previously utilized mice that lack Del-1 alone or Del-1 together with other molecules of the immune system. The researchers found that mutant mice lacking Del-1 had more severe attacks of the EAE than normal mice, with more damage to myelin, the fatty sheath that coats neurons and helps in the transmission of signals along the cell. Loss of this substance is the hallmark of MS and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Mice without Del-1 that had been induced to get EAE also had significantly higher numbers of inflammatory cells in their spinal cords at the disease's peak, a fact that further experiments revealed was due to increased levels of the signaling molecule IL-17.

Mice that were induced to get EAE that lacked both Del-1 and the receptor for IL-17 had a much milder form of the disease compared to mice that lacked only Del-1. These doubly depleted mice also had fewer neutrophils and inflammation in their spinal cords.

With a greater understanding of how Del-1 acts in EAE, the researchers were curious whether simply replacing Del-1 might act as a therapy for the disease. They waited until mice had had an EAE attack, akin to a flare-up of MS in human patients, and then administered Del-1. They were pleased to find that these mice did not experience further episodes of the disease.

"This treatment prevented further disease relapse," Chavakis said. "Thus, administration of soluble Del-1 may provide the platform for developing novel therapeutic approaches for neuroinflammatory and demyelinating diseases, especially multiple sclerosis."

The team is pursuing further work on Del-1 to see if they can identify a subunit of the protein that could have the same therapeutic effect.

"It's amazing that our work in periodontitis have found application in a central nervous system disease," Hajishengallis said. "This shows that periodontitis can be a paradigm for other medically important inflammatory diseases."

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Novartis Foundation for Therapeutical Research, the NIH Intramural Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, the Extramural Program of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the European Research Council.

DALLAS - November 11, 2014 - UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have determined the specific type of cell that gives rise to large, disfiguring tumors called plexiform neurofibromas, a finding that could lead to new therapies for preventing growth of these tumors.

"This advance provides new insight into the steps that lead to tumor development and suggests ways to develop therapies to prevent neurofibroma formation where none exist today," said Dr. Lu Le, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at UT Southwestern and senior author of the study, published online and ...

As scientists probe the molecular underpinnings of why some people are prone to obesity and some to leanness, they are discovering that weight maintenance is more complicated than the old "calories in, calories out" adage.

A team of researchers led by the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine's Kendra K. Bence have now drawn connections between known regulators of body mass, pointing to possible treatments for obesity and metabolic disorders.

Their work also presents intriguing clues that these same molecular pathways may play a role in learning ...

Salivary mucins, key components of mucus, actively protect the teeth from the cariogenic bacterium, Streptococcus mutans, according to research published ahead of print in Applied and Environmental Microbiology. The research suggests that bolstering native defenses might be a better way to fight dental caries than relying on exogenous materials, such as sealants and fluoride treatment, says first author Erica Shapiro Frenkel, of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

S. mutans attaches to teeth using sticky polymers that it produces, eventually forming a biofilm, a protected ...

From this week's Eos: Scientists Engage With the Public During Lava Flow Threat

On 27 June, lava from Kīlauea, an active volcano on the island of Hawai`i, began flowing to the northeast, threatening the residents in Pāhoa, a community in the District of Puna, as well as the only highway accessible to this area. Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey's Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) and the Hawai`i County Civil Defense have been monitoring the volcano's lava flow and communicating with affected residents through public meetings since 24 August. Eos recently ...

The majority of people - including healthcare professionals - are unable to visually identify whether a person is a healthy weight, overweight or obese according to research by psychologists at the University of Liverpool.

Researchers from the University's Institute of Psychology, Health and Society asked participants to look at photographs of male models and categorise whether they were a healthy weight, overweight or obese according to World Health Organisation (WHO) Body Mass Index (BMI) guidelines.

They found that the majority of participants were unable to correctly ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Tiny, thin microtubes could provide a scaffold for neuron cultures to grow so that researchers can study neural networks, their growth and repair, yielding insights into treatment for degenerative neurological conditions or restoring nerve connections after injury.

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Wisconsin-Madison created the microtube platform to study neuron growth. They posit that the microtubes could one day be implanted like stents to promote neuron regrowth at injury sites or to treat disease.

"This ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Crop producers and scientists hold deeply different views on climate change and its possible causes, a study by Purdue and Iowa State universities shows.

Associate professor of natural resource social science Linda Prokopy and fellow researchers surveyed 6,795 people in the agricultural sector in 2011-2012 to determine their beliefs about climate change and whether variation in the climate is triggered by human activities, natural causes or an equal combination of both.

More than 90 percent of the scientists and climatologists surveyed said they ...

Located hundreds of miles inland from the nearest ocean, the Midwest is unaffected by North Atlantic hurricanes.

Or is it?

With the Nov. 30 end of the 2014 hurricane season just weeks away, a University of Iowa researcher and his colleagues have found that North Atlantic tropical cyclones in fact have a significant effect on the Midwest. Their research appears in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Gabriele Villarini, UI assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, studied the discharge records collected at 3,090 U.S. Geological Survey ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Glycogen storage disorders, which affect the body's ability to process sugar and store energy, are rare metabolic conditions that frequently manifest in the first years of life. Often accompanied by liver and muscle disease, this inability to process and store glucose can have many different causes, and can be difficult to diagnose. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri who have studied enzymes involved in metabolism of bacteria and other organisms have catalogued the effects of abnormal enzymes responsible for one type of this disorder in humans. ...

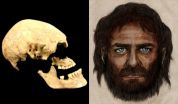

What if you researched your family's genealogy, and a mysterious stranger turned out to be an ancestor?

That's the surprising feeling had by a team of scientists who peered back into Europe's murky prehistoric past thousands of years ago. With sophisticated genetic tools, supercomputing simulations and modeling, they traced the origins of modern Europeans to three distinct populations.

The international research team published their September 2014 results in the journal Nature.

XSEDE, the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, provided the computational ...