(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Modeling used to forecast fluctuations in the stock market has been discovered to predict aspects of animal behavior. The movement of zebrafish when mapped is very similar to the stochastic...

Click here for more information.

In an unexpected mashup of financial and mechanical engineering, researchers have discovered that the same modeling used to forecast fluctuations in the stock market can be used to predict aspects of animal behavior. Their work proposes an unprecedented model for in silico--or computer-based--simulations of animal behavior. The findings were published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

The team, led by Maurizio Porfiri, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and director of the school's Dynamical Systems Laboratory, is more accustomed to studying the social behavior of zebrafish--a freshwater species often used in experiments due to its genetic similarity to humans. Porfiri has drawn considerable attention for his interdisciplinary research on the factors that influence zebrafish collective behavior.

However, designing procedures and conditions for animal experiments are time-intensive, and despite careful planning, many experiments yield mixed data. Porfiri and his team, comprising postdoctoral fellow Ross P. Anderson, doctoral student Violet Mwaffo, and former postdoctoral fellow Sachit Butail (now assistant professor at Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology Delhi), set out to develop a mathematical model of animal behavior that could predict the outcome or improve the effectiveness of experiments and minimize the number of fish used in them.

When mapping the movement of zebrafish as they swam, Porfiri and his colleagues observed that the species does not move in a continuous pattern; rather, it swims in a signature style characterized by coasting periods followed by sharp turns. As they plotted the turn rate of the fish over time, the researchers noticed that their data, with its small variations followed by large dips (reflecting fast turns), looked very different from the turn rate of other fish but very similar to another type of data, where such volatility is not only common but well studied: the stock market.

The team embraced the mathematical model known as a stochastic jump process, a term used by financial engineers and economists to describe the price jumps of financial assets over time. Using many of the same tools employed in financial analysis, the researchers were able to create a mathematical model of zebrafish swimming, mining video footage from previous experimental sessions to seed what they hope will become a robust database of zebrafish behavior under varying circumstances.

"We realized that if we could simulate the swimming behavior of these fish using a computer, we could test and predict their responses to new stimuli, whether that is the introduction or removal of a shoal mate, the presence of a robotic fish, or even exposure to alcohol," Porfiri said. "In behavior studies, you can easily utilize thousands of test subjects to explore different variables. This will allow researchers to replace some of that experimentation with computer modeling."

Porfiri emphasized that this mathematical model of animal behavior will also allow researchers to make better use of their data following experiments, not just beforehand. "The data that result from zebrafish experiments look quite messy initially," Porfiri said. "Giving researchers a model they can use to compare, filter, and refine their analysis afterwards will allow them to maximize data for better results."

Porfiri and his team plan to continue to add data to their model with the hope of creating a toolbox that all researchers engaged in this field of study can utilize.

The idea of incorporating financial engineering to model zebrafish behavior came from Mwaffo, now a doctoral student in Porfiri's lab who had earned his master's degree in financial engineering from the NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation. The full paper, "A Jump Persistent Turning Walker to Model Zebrafish Locomotion" is at http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/12/102/20140884.short?rss=1.

The NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering dates to 1854, when the NYU School of Civil Engineering and Architecture as well as the Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute (widely known as Brooklyn Poly) were founded. Their successor institutions merged in January 2014 to create a comprehensive school of education and research in engineering and applied sciences, rooted in a tradition of invention, innovation and entrepreneurship. In addition to programs at its main campus in downtown Brooklyn, it is closely connected to engineering programs in NYU Abu Dhabi and NYU Shanghai, and it operates business incubators in downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn. For more information, visit http://engineering.nyu.edu.

A study led by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators has identified what appears to be a molecular switch controlling inflammatory processes involved in conditions ranging from muscle atrophy to Alzheimer's disease. In their report published in Science Signaling, the research team found that the action of the signaling molecule nitric oxide on the regulatory protein SIRT1 is required for the induction of inflammation and cell death in cellular and animal models of several aging-related disorders.

"Since different pathological mechanisms have been identified ...

November 12, 2014 - "I am the smartest kid in class." We all want our kids to be self-confident, but unrealistic perceptions of their academic abilities can be harmful. These unrealistic views, a new study of eighth-graders finds, damage the a child's relationship with others in the classroom: The more one student feels unrealistically superior to another, the less the two students like each other.

Katrin Rentzsch of the University of Bamberg in Germany first became interested in the effects of such self-perceptions when she was studying how people became labeled as ...

LOS ANGELES -- New research from Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) bolsters evidence that exposure to tobacco smoke and near-roadway air pollution contribute to the development of obesity.

The study, to be posted online Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2014 in Environmental Health Perspectives, shows increased weight gain during adolescence in children exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke or near-roadway air pollution, compared to children with no exposure to either of these air pollutants. The study is one of the first to look at the combined effects on ...

Applying a thin film of metallic oxide significantly boosts the performance of solar panel cells--as recently demonstrated by Professor Federico Rosei and his team at the Énergie Matériaux Télécommunications Research Centre at Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS). The researchers have developed a new class of materials comprising elements such as bismuth, iron, chromium, and oxygen. These "multiferroic" materials absorb solar radiation and possess unique electrical and magnetic properties. This makes them highly promising for solar technology, ...

VCU Massey Cancer Center and VCU Institute of Molecular Medicine (VIMM) researchers discovered a unique approach to treating pancreatic cancer that may be potentially safe and effective. The treatment method involves immunochemotherapy - a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, which uses the patient's own immune system to help fight against disease. This pre-clinical study, led by Paul B. Fisher, M.Ph., Ph.D., and Luni Emdad, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., found that the delivery of [pIC]PEI - a combination of the already-established immune-modulating molecule, polyinosine-polycytidylic ...

High blood pressure - already a massive hidden killer in Nigeria - is set to sharply rise as the country adopts western lifestyles, a study suggests.

Researchers who conducted the first up-to-date nationwide estimate of the condition in Nigeria warn that this will strain the country's already-stretched health system.

Increased public awareness, lifestyle changes, screening and early detection are vital to tackle the increasing threat of the disease, they say.

High blood pressure - also known as hypertension - is twice as high in Nigeria compared with other East ...

Scientists have demonstrated for the first time that a single-dose, needleless Ebola vaccine given to primates through their noses and lungs protected them against infection for at least 21 weeks. A vaccine that doesn't require an injection could help prevent passing along infections through unintentional pricks. They report the results of their study on macaques in the ACS journal Molecular Pharmaceutics.

Maria A. Croyle and colleagues note that in the current Ebola outbreak, which is expected to involve thousands more infections and deaths before it's over, an effective ...

Geneticists at Heidelberg University Hospital's Department of Molecular Human Genetics have used a new mouse model to demonstrate the way a certain genetic mutation is linked to a type of autism in humans and affects brain development and behavior. In the brain of genetically altered mice, the protein FOXP1 is not synthesized, which is also the case for individuals with a certain form of autism. Consequently, after birth the brain structures degenerate that play a key role in perception. The mice also exhibited abnormal behavior that is typical of autism. The new mouse ...

An electronic "tongue" could one day sample food and drinks as a quality check before they hit store shelves. Or it could someday monitor water for pollutants or test blood for signs of disease. With an eye toward these applications, scientists are reporting the development of a new, inexpensive and highly sensitive version of such a device in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

S. V. Litvinenko and colleagues explain that an electronic tongue is an analytical instrument that mimics how people and other mammals distinguish tastes. Tiny sensors detect substances ...

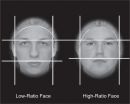

The structure of a soccer player's face can predict his performance on the field--including his likelihood of scoring goals, making assists and committing fouls--according to a study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The scientists studied the facial-width-to-height ratio (FHWR) of about 1,000 players from 32 countries who competed in the 2010 World Cup. The results, published in the journal Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, showed that midfielders, who play both offense and defense, and forwards, who lead the offense, with higher FWHRs ...