(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, Nov. 19, 2014--When the 2014 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded this October to three Japanese-born scientists for the invention of blue light emitting diodes (LEDs), the prize committee declared LED lamps would light the 21st century. Now researchers from the Netherlands have found a novel way to ensure the lights of the future not only are energy efficient but also emit a cozy warmth.

"We demonstrated a seemingly simple - but in fact sophisticated - way to create LED lights that change in a natural way to a cozy, warm white color when dimmed," said Hugo Cornelissen, a principal scientist in the Optics Research Department at Philips Research Eindhoven, a corporate scientific research entity owned by the company Royal Philips in the Netherlands.

Cornelissen and his colleagues from the Eindhoven University of Technology, Netherlands describe their new LEDs in a paper published today in The Optical Society's (OSA) open-access journal Optics Express.

Incandescent lamps naturally emit warmer colors when dimmed, and Cornelissen said our general preference for redder colors in low-light situations might even have developed far back in time, when humans "experienced the daily rhythm of sunrise, bright daylight at noon, and sunset, each with their corresponding color temperatures."

LEDs, however, don't normally change color at different light intensities. Other groups have used multiple color LEDs and complex control circuitry to make lights that turn redder as the power is turned down. The added complexity comes with its drawbacks: multiple components can increase the cost and the risk of failure, and mixing the light from multiple LEDs without creating color shadows and other light artifacts is a tricky business.

The Dutch research team tried an entirely different approach to creating cozy LEDs. The scientists had noticed that when they embedded LEDs in coated textiles or transparent materials, the color of the emitted light would sometimes change.

"After finding the root cause of these effects and quantitatively understanding the observed color shift, we thought of a way to turn the undesired color changes into a beneficial feature," said Cornelissen.

Starting with White LEDs

They began with cold white LEDs, which can be made from blue LEDs surrounded by a material known as a phosphor. Part of the blue light is absorbed by the phosphor and re-emitted at a different color. The multiple colors combine to form white light.

Cornelissen and his colleagues knew that the color of the white light could be shifted toward the warmer end of the spectrum if more of the blue light is absorbed and re-emitted by the phosphor. What they describe in the new paper is how they developed a novel - and temperature-dependent - way to create this shift.

The scientists made a coating from a composite of liquid crystal and polymeric material. The composite normally scatters light, but if it is heated above 48 degrees Celsius (approximately 118 degrees Fahrenheit), the liquid crystal molecules rearrange and the composite becomes transparent.

When the team covered white LEDs with the coating and turned up the power, the temperature increased enough to make the coating transparent, and the LEDs emitted a cold white color. When the power was turned down, the coating reorganized into a scattering material that bounced back more of the blue light into the phosphor, generating a warmer glow.

The scientists later fine-tuned the LED design and used multiple phosphors to create lights that comply with industry lighting standards across a range of currents and colors.

"We might see products on the market in two years, but first we'll have to prove reliability over time," Cornelissen said. "That is one of the important things to do next."

The team believes the new lights could help speed up the acceptance and widespread use of LED technology, especially in the household and hospitality markets, "where there is a need to create a warm and cozy atmosphere," Cornelissen said.

INFORMATION:

Paper: "Thermoresponsive scattering coating for smart white LEDs," J. Bauer et al., Optics Express, Vol. 22 Issue S7, pp. A1868-A1879 (2014).

ARTICLE LINK: http://www.opticsinfobase.org/oe/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-22-S7-A1868

About Optics Express

Optics Express reports on new developments in all fields of optical science and technology every two weeks. The journal provides rapid publication of original, peer-reviewed papers. It is published by The Optical Society and edited by Andrew M. Weiner of Purdue University. Optics Express is an open-access journal and is available at no cost to readers online at http://www.OpticsInfoBase.org/OE.

About OSA

Founded in 1916, The Optical Society (OSA) is the leading professional society for scientists, engineers, students and business leaders who fuel discoveries, shape real-world applications and accelerate achievements in the science of light. Through world-renowned publications, meetings and membership programs, OSA provides quality research, inspired interactions and dedicated resources for its extensive global network of professionals in optics and photonics. For more information, visit http://www.osa.org

Blueberries are super stars among health food advocates, who tout the fruit for not only promoting heart health, better memory and digestion, but also for improving night vision. Scientists have taken a closer look at this latter claim and have found reason to doubt that the popular berry helps most healthy people see better in the dark. Their report appears in ACS' Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry.

Wilhelmina Kalt and colleagues note that studies published decades ago provided the first hints that blueberries might improve people's night vision. Later lab experiments ...

A new report from the Research Alliance for New York City Schools gives a first look at patterns of college enrollment, persistence, and completion for New York City high school students.

"It is rare to be able to track students' trajectories through high school and post-secondary education," said James J. Kemple, executive director of the Research Alliance. "This is the first such study focused on New York City, and it has revealed some encouraging signs, as well as areas in need of greater attention. The findings provide a strong foundation for learning more about the ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. --U.S. children's hospitals delivering the highest-quality care for children undergoing heart surgery, also appear to provide care most efficiently at a low cost, according to research led by the University of Michigan and presented Tuesday at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in Chicago.

Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects, and each year more than 30,000 congenital heart operations are performed across U.S. children's hospitals. Congenital heart defects are also one of the most expensive pediatric conditions to ...

A Georgia Tech professor is offering an alternative to the celebrated "Turing Test" to determine whether a machine or computer program exhibits human-level intelligence. The Turing Test - originally called the Imitation Game - was proposed by computing pioneer Alan Turing in 1950. In practice, some applications of the test require a machine to engage in dialogue and convince a human judge that it is an actual person.

Creating certain types of art also requires intelligence observed Mark Riedl, an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech, ...

Empagliflozin (trade name Jardiance) has been approved since May 2014 for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in whom diet and exercise alone do not provide adequate glycaemic control. The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined in a dossier assessment whether the drug offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapies in these patient groups.

According to the findings, such an added benefit is not proven: For four of five research questions, the manufacturer presented no relevant data in its dossier. For the fifth ...

Following a 5,000 km long ocean survey, research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents a new way to measure how the acidification of water is affecting marine ecosystems over an entire oceanic basin.

As a result of man-made emissions, the content of CO2 in the atmosphere and oceans has increased dramatically during recent decades. In the ocean, the accumulating CO2 is gradually acidifying the surface waters, making it harder for shelled organisms like corals (Figure 1) and certain open sea plankton to build their calcium carbonate ...

Flexible electronic sensors based on paper -- an inexpensive material -- have the potential to some day cut the price of a wide range of medical tools, from helpful robots to diagnostic tests. Scientists have now developed a fast, low-cost way of making these sensors by directly printing conductive ink on paper. They published their advance in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Anming Hu and colleagues point out that because paper is available worldwide at low cost, it makes an excellent surface for lightweight, foldable electronics that could be made and ...

Now that car makers have demonstrated through hybrid vehicle success that consumers want less-polluting tailpipes, they are shifting even greener. In 2015, Toyota will roll out the first hydrogen fuel-cell car for personal use that emits only water. An article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, explains how hydrogen could supplant hybrid and electric car technology -- and someday, even spur the demise of the gasoline engine.

Melody M. Bomgardner, a senior editor at C&EN, notes that the first fuel-cell vehicles ...

Exposure to peanut proteins in household dust may be a trigger of peanut allergy, according to a study published today in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

The study was conducted in 359 children aged 3-15 months taking part in the NIH-sponsored Consortium for Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) study. These children were at high risk of developing a peanut allergy based on having likely milk or egg allergy or eczema. The study found that the risk of having strong positive allergy tests to peanut increased with increasingly higher amounts of peanut found in ...

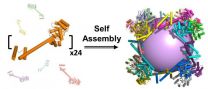

UCLA biochemists have created the largest-ever protein that self-assembles into a molecular "cage." The research could lead to synthetic vaccines that protect people from the flu, HIV and other diseases.

At a size hundreds of times smaller than a human cell, it also could lead to new methods of delivering pharmaceuticals inside of cells, or to the creation of new nanoscale materials.

The protein assembly, which is shaped like a cube, was constructed from 24 copies of a protein designed in the laboratory of Todd Yeates, a UCLA professor of chemistry and biochemistry. ...