(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--Scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered a powerful one-two punch for countering a common genetic mutation that often leads to drug-resistant cancers. The dual-drug therapy--with analogs already in use for other diseases--doubled the survival rate of mice with lung cancer and halted cancer in pancreatic cells.

Lung cancer, which affects nonsmokers as well as smokers, is the most common cancer worldwide, causing 1.6 million deaths a year, far more than pancreatic, breast and colon cancer combined. About 30 percent of the most common type of lung cancer (non-small) contains a mutation in a gene called KRAS. This mutation can also lead to hard-to-treat cancer in the pancreas, thyroid and colon.

"There really have been no effective treatments to target the KRAS mutation so far," says Inder Verma, a professor in the Laboratory of Genetics and American Cancer Society Professor of Molecular Biology. "We found a drug combination that successfully targets KRAS and stops tumor growth in the mouse model."

The new discovery, detailed November 19 in Science Translational Medicine, shows how the two-pronged attack successfully hindered KRAS and other cellular processes to halt or shrink tumor growth.

When activated, mutated KRAS clings to cell membranes and recruits proteins to ramp up cancer growth. Researchers have developed drugs to disable enzymes that tether KRAS to the cell membrane, but these drugs typically ended up being toxic because those enzymes are needed in the body for normal functions.

"The Achilles' heel of KRAS is its movement to the membrane," says Verma, who is also holder of Salk's Irwin and Joan Jacobs Chair in Exemplary Life Science.

The researchers took a new approach to targeting this membrane interaction when they noticed that a drug called Zometa, typically used to stop the breakdown and growth of cells in bone disease, also interfered with cell membrane interactions. In previous work, the team added carbon chains to a molecule similar to Zometa, to create a lipophilic bisphosphonate (BP) that blocked KRAS from attaching to the cell membrane.

"For the first time, we had the ability to interfere with KRAS without being completely toxic," says Verma.

This, however, wasn't enough. Tumors were still proliferating, in part because the new BP led to failed attempts of a process called autophagy, where cells, under stress, self-destruct and break down into nutrients that can be used by other cells.

Autophagy can be both good and bad in fighting cancer: in some cases, autophagy prompts cancer cells to die; in other settings, it creates a cellular environment that helps tumors thrive. With the BP treatment, cells began the process of autophagy but failed, leading to junk protein accumulation and an inflamed environment that helped the tumors to survive.

But, as demonstrated in the new work, when the researchers added a chemical called rapamycin, cells were able to carry out autophagy successfully and prevented tumor cells from proliferating. Rapamycin, discovered in the 1970s, is used in the clinic for preventing organ rejection and has also been linked to anti-cancer effects.

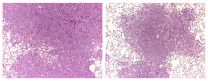

"We found if we also activated autophagy--with the rapamycin--and combine it with the inhibitor of the cell membrane--the BP--there were significant cell deaths in the tumors," says Yifeng Xia, Salk researcher and first author of the new work.

VIDEO:

A mutation of the KRAS gene leads to a common and hard-to-treat lung cancer. Salk researchers find a powerful combination therapy that targets this cancer.

Click here for more information.

When they injected the combination in mouse lung tumors, tumors shrunk or stopped growing. The study also found that a pancreatic cancer cell line responded to the dual treatment. Next, the team plans to test toxicity of the new BP. The group is also working with the University of California, San Diego, Moores Cancer Center to design human clinical trials to test the dual therapy.

"Those two drugs have not been used together as far as we know for KRAS-related cancer treatment," adds Xia. "We are excited about the potential and that these molecules are already being used in clinical trials in some form."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Verma and Xia, authors on the paper included Shen Shen, Narayana Yeddula, Wolfgang Fischer and William Low of the Salk Institute; Yi-Liang Liu, Wei Zhu, Francisco Guerra and Eric Oldfield of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and Yonghua Xie, Xiaoying Zhou and Yonghui Zhang of the Tsinghua University.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Ipsen Biomeasure, the H.N. and Frances C. Berger Foundation and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

WASHINGTON, D.C. - An antidepressant commonly prescribed for women with postpartum depression may restore connections between cells in brain regions that are negatively affected by chronic stress during pregnancy, new research suggests.

Ohio State University scientists found that rats that had been chronically stressed during pregnancy showed depressive-like behaviors after giving birth, and structures in certain areas of their brains were less complex than in unstressed rats. After receiving the drug for three weeks, these rats had no depressive symptoms and neurons ...

New York City residents' movement around the city was perturbed, but resumed less than 24-hours after Hurricane Sandy, according to a study published November 19, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Qi Wang and John Taylor from Virginia Tech.

Tropical cyclones, including hurricanes and typhoons, are severe natural disasters that can cause tremendous loss of human life and suffering. Our knowledge of peoples' movements during natural disasters is so far limited due to a lack of data. The authors of this article studied human mobility using movement data from individuals ...

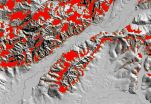

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Engineers have created a new way to use lidar technology to identify and classify landslides on a landscape scale, which may revolutionize the understanding of landslides in the U.S. and reveal them to be far more common and hazardous than often understood.

The new, non-subjective technology, created by researchers at Oregon State University and George Mason University, can analyze and classify the landslide risk in an area of 50 or more square miles in about 30 minutes - a task that previously might have taken an expert several weeks to months. It can ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A new study by a Florida State University biologist shows that bleaching events brought on by rising sea temperatures are having a detrimental long-term impact on coral.

Professor Don Levitan, chair of the Department of Biological Science, writes in the latest issue of Marine Ecology Progress Series that bleaching -- a process where high water temperatures or UV light stresses the coral to the point where it loses its symbiotic algal partner that provides the coral with color -- is also affecting the long-term fertility of the coral.

"Even corals ...

New research has found that one of the world's most prolific bacteria manages to afflict humans, animals and even plants by way of a mechanism not before seen in any infectious microorganism -- a sense of touch. This unique ability helps make the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa ubiquitous, but it also might leave these antibiotic-resistant organisms vulnerable to a new form of treatment.

Pseudomonas is the first pathogen found to initiate infection after merely attaching to the surface of a host, Princeton University and Dartmouth College researchers report in the journal ...

A social sensing game created at Illinois allows researchers to study natural interactions between children, collect large amounts of data about those interactions and test theories about youth aggression and victimization.

The game's behavior analyses effectively identify classroom bullies, even revealing peer aggression that goes undetected by traditional research methods, the researchers say.

The game's developers say it is an improvement over traditional research methods, such as questionnaires, which do not assess interactions between youth in real time.

"What ...

When the mouse and human genomes were catalogued more than 10 years ago, an international team of researchers set out to understand and compare the "mission control centers" found throughout the large stretches of DNA flanking the genes. Their long-awaited report, published Nov. 19 in the journal Nature suggests why studies in mice cannot always be reproduced in humans. Importantly, the scientists say, their work also sheds light on the function of DNA's regulatory regions, which are often to blame for common chronic human diseases.

"Most of the differences between mice ...

Microbiologists at NYU Langone Medical Center say they have what may be the first strong evidence that the natural presence of viruses in the gut -- or what they call the 'virome' -- plays a health-maintenance and infection-fighting role similar to that of the intestinal bacteria that dwell there and make up the "microbiome."

In a series of experiments in mice that took two years to complete, the NYU Langone team found that infection with the common murine norovirus, or MNV, helped mice repair intestinal tissue damaged by inflammation and helped restore the gut's immune ...

For years, scientists have considered the laboratory mouse one of the best models for researching disease in humans because of the genetic similarity between the two mammals. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found that the basic principles of how genes are controlled are similar in the two species, validating the mouse's utility in clinical research.

However, there are important differences in the details of gene regulation that distinguish us as a species.

"At the end of the day, a lot of the genes are identical between a mouse and ...

For more than a century, the laboratory mouse (Mus musculus) has stood in for humans in experiments ranging from deciphering disease and brain function to explaining social behaviors and the nature of obesity. The small rodent has proven to be an indispensable biological tool, the basis for decades of profound scientific discovery and medical progress.

But in new findings published online Nov. 19 in the journal Nature, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Ludwig Cancer Research, with colleagues across the country and world, have ...