Biology trumps chemistry in open ocean

New framework advances understanding of phytoplankton nutrient assimilation

2014-11-24

(Press-News.org) Single-cell phytoplankton in the ocean are responsible for roughly half of global oxygen production, despite vast tracts of the open ocean that are devoid of life-sustaining nutrients. While phytoplankton's ability to adjust their physiology to exploit limited nutrients in the open ocean has been well documented, little is understood about how variations in microbial biodiversity -- the number and variety of marine microbes - affects global ocean function.

In a paper published in PNAS on Monday November 24, scientists laid out a robust new framework based on in situ observations that will allow scientists to describe and understand how phytoplankton assimilate limited concentrations of phosphorus, a key nutrient, in the ocean in ways that better reflect what is actually occurring in the marine environment. This is an important advance because nutrient uptake is a central property of ocean biogeochemistry, and in many regions controls carbon dioxide fixation, which ultimately can play a role in mitigating climate change.

"Until now, our understanding of how phytoplankton assimilate nutrients in an extremely nutrient-limited environment was based on lab cultures that poorly represented what happens in natural populations," explained Michael Lomas of Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, who co-led the study with Adam Martiny of University of California - Irvine, and Simon Levin and Juan Bonachela of Princeton University. "Now we can quantify how phytoplankton are taking up nutrients in the real world, which provides much more meaningful data that will ultimately improve our understanding of their role in global ocean function and climate regulation."

To address the knowledge gap about the globally-relevant ecosystem process of nutrient uptake, researchers worked to identify how different levels of microbial biodiversity influenced in situ phosphorus uptake in the Western Subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Specifically, they focused on how different phytoplankton taxa assimilated phosphorus in the same region, and how phosphorus uptake by those individual taxa varied across regions with different phosphorus concentrations. They found that phytoplankton were much more efficient at assimilating vanishingly low phosphorus concentrations than would have been predicted from culture research. Moreover, individual phytoplankton continually optimized their ability to assimilate phosphorus as environmental phosphorus concentrations increased. This finding runs counter to the commonly held, and widely used, view that their ability to assimilate phosphorus saturates as concentrations increase.

"Prior climate models didn't take into account how natural phytoplankton populations vary in their ability to take up key nutrients, "said Martiny. "We were able to fill in this gap through fieldwork and advanced analytical techniques. The outcome is the first comprehensive in situ quantification of nutrient uptake capabilities among dominant phytoplankton groups in the North Atlantic Ocean that takes into account microbial biodiversity. "

INFORMATION:

Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, an independent not-for-profit research institution on the coast of Maine, conducts research ranging from microbial oceanography to large-scale ocean processes that affect the global environment. Recognized as a leader in Maine's emerging innovation economy, the Laboratory's research, education, and technology transfer programs are spurring significant economic growth in the state.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-24

DURHAM, N.C. -- Nearly four decades of observations of Tanzanian chimpanzees has revealed that the mothers of sons are about 25 percent more social than the mothers of daughters. Boy moms were found to spend about two hours more per day with other chimpanzees than the girl moms did.

Chimpanzees have a male-dominated society in which rank is a constant struggle and females with infants might face physical violence and even infanticide. It would be safer in general to just avoid groups where aggressive males are present, yet the mothers of sons choose to do so anyway.

"It ...

2014-11-24

A National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded research team has successfully tested an autonomous underwater vehicle, AUV, that can produce high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of Antarctic sea ice. SeaBED, as the vehicle is known, measured and mapped the underside of sea-ice floes in three areas off the Antarctic Peninsula that were previously inaccessible.

The results of the research were published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience. Scientists at the Institute of Antarctic and Marine Science (Australia), Antarctic Climate and Ecosystem Cooperative Research ...

2014-11-24

Coral reefs persist in a balance between reef construction and reef breakdown. As corals grow, they construct the complex calcium carbonate framework that provides habitat for fish and other reef organisms. Simultaneously, bioeroders, such as parrotfish and boring marine worms, breakdown the reef structure into rubble and the sand that nourishes our beaches. For reefs to persist, rates of reef construction must exceed reef breakdown. This balance is threatened by increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which causes ocean acidification (decreasing ocean pH). Prior research ...

2014-11-24

LIND, Wash. - In the world's driest rainfed wheat region, Washington State University researchers have identified summer fallow management practices that can make all the difference for farmers, water and soil conservation, and air quality.

Wheat growers in the Horse Heaven Hills of south-central Washington farm with an average of 6-8 inches of rain a year. Wind erosion has caused blowing dust that exceeded federal air quality standards 20 times in the past 10 years.

"Some of these events caused complete brown outs, zero visibility, closed freeways," said WSU research ...

2014-11-24

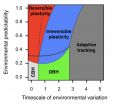

Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a model that mimics how differently adapted populations may respond to rapid climate change. Their findings demonstrate that depending on a population's adaptive strategy, even tiny changes in climate variability can create a "tipping point" that sends the population into extinction.

Carlos Botero, postdoctoral fellow with the Initiative on Biological Complexity and the Southeast Climate Science Center at NC State and assistant professor of biology at Washington State University, wanted to find out how diverse ...

2014-11-24

Last year, University of Pennsylvania researchers Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin published a mathematical explanation for why cooperation and generosity have evolved in nature. Using the classical game theory match-up known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, they found that generous strategies were the only ones that could persist and succeed in a multi-player, iterated version of the game over the long term.

But now they've come out with a somewhat less rosy view of evolution. With a new analysis of the Prisoner's Dilemma played in a large, evolving population, they ...

2014-11-24

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Nov. 24, 2014, 3 P.M.) -- Researchers at Tufts University, in collaboration with a team at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, have demonstrated a resorbable electronic implant that eliminated bacterial infection in mice by delivering heat to infected tissue when triggered by a remote wireless signal. The silk and magnesium devices then harmlessly dissolved in the test animals. The technique had previously been demonstrated only in vitro. The research is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early ...

2014-11-24

A Jackson Laboratory research team has found that the misfolded proteins implicated in several cardiac diseases could be the result not of a mutated gene, but of mistranslations during the "editing" process of protein synthesis.

In 2006 the laboratory JAX Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Susan Ackerman, Ph.D., showed that the movement disorders in a mouse model with a mutation called sti (for "sticky," referring to the appearance of the animal's fur) were due to malformed proteins resulting from the incorporation of the wrong amino acids into proteins ...

2014-11-24

Research that provides a new understanding of how bacterial toxins target human cells is set to have major implications for the development of novel drugs and treatment strategies.

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are toxins produced by major bacterial pathogens, most notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and group A streptococci, which collectively kill millions of people each year.

The toxins were thought to work by interacting with cholesterol in target cell membranes, forming pores that bring about cell death.

Published today in the prestigious journal Proceedings ...

2014-11-24

A commonly prescribed muscle relaxant may be an effective treatment for a rare but devastating form of diabetes, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

The drug, dantrolene, prevents the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells both in animal models of Wolfram syndrome and in cell models derived from patients who have the illness.

Results are published Nov. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Online Early Edition.

Patients with Wolfram syndrome typically develop type 1 diabetes as very young children ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Biology trumps chemistry in open ocean

New framework advances understanding of phytoplankton nutrient assimilation