(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- Sixty years ago, the plows ended their reign and the fields were allowed to return to nature -- allowed to become the woodland forests they once were.

But even now, the ghosts of land-use past haunt these woods. New research by Philip Hahn and John Orrock at the University of Wisconsin-Madison on the recovery of South Carolina longleaf pine woodlands once used for cropland shows just how long lasting the legacy of agriculture can be in the recovery of natural places.

By comparing grasshoppers found at woodland sites once used for agriculture to similar sites never disturbed by farming, Hahn and Orrock show that despite decades of recovery, the numbers and types of species found in each differ, as do the understory plants and other ecological variables, like soil properties. The findings were published today in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

While several studies have examined the recovery of plant species at such sites, this is the first to examine the impacts of historical agriculture on animals.

The findings have implications for conservationists, land-use planners, policymakers and land managers looking to prevent habitat destruction or promote ecological recovery of natural spaces. Hahn and Orrock suggest new strategies may be needed in these disturbed environments.

The findings also challenge conventional ecological wisdom, in ways the scientists did not expect.

"Ecologically, grasshoppers are at the heart of the food chain," says Hahn, a graduate student in Orrock's laboratory. Orrock is an associate professor in the Department of Zoology. "They eat the plants and then they're eaten by others: other insects, reptiles, birds."

Like the proverbial canary in the coal mine, the grasshoppers in the study served as a signal of the recovery of areas once used for agriculture. Building on past research that shows post-agricultural sites have poorer-quality soil and differences in the types of plant species that grow back, Hahn surveyed the plants, soil quality and grasshoppers found at 36 study sites.

He wanted to know whether earlier land use changed the numbers and types of grasshoppers found at each site and whether the relationships between the insects, plants and the environment were altered.

Sweeping through the plants in the understory with a tool called -- fittingly -- a sweep net, Hahn collected grasshoppers and recorded the types and numbers of those he found in both undisturbed and post-agricultural woodlands. He collected 459 of the hopping critters, representing numerous different types of grasshopper.

"The humble grasshopper, ubiquitous, yet cryptic," Orrock reflects; they're not as visible or well known as the popular deer.

The researchers found differences in the types of grasshoppers collected in each, related to the understory plants that grew and the hardness of the soil.

In remnant woodlands with no history of agriculture, more plant types equated to greater numbers of grasshoppers, an expected and traditional link between plants and the species that depend on them for food and shelter. This connection did not exist in areas once used as cropland, calling into question a long-held dogma of ecological relationships.

"It challenges what we know," Orrock says. "If it's true that the past influences ecological relationships in ways that we can't predict, then all bets are off."

The researchers say this is especially important as land use continues to change, with some areas of the U.S. converting wild spaces into new agricultural lands and others abandoning massive plots once used to grow food.

"We've wondered why it is -- 60 years after we've stopped plowing -- there are these legacy effects of land use on communities," says Orrock. "Why has what we did so long ago lasted? Why hasn't nature recovered?"

The boundaries can be so distinct in the woodlands they studied, he says, that it's easy to tell within four meters where the plowline once ended.

"It's remarkable how far the past reaches into the future," says Orrock.

The knowledge, the researchers say, presents opportunities to do better. For instance, Hahn believes new strategies can be tried, like reintroducing once-native plant species to abandoned sites earlier on, or proactively working on restoring the health of the soil. Conversely, more conservation and management efforts could be spent promoting less habitat degradation in the first place.

"Before the research started, we thought most bad things could be undone in a decade," Orrock says. "The good news is, at least we know where we are and it's a start. We know business as usual might not work."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program, the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, and the UW-Madison Department of Zoology.

-- Kelly April Tyrrell, ktyrrell2@wisc.edu, 608-262-9772

CONTACT: Phil Hahn, 608-262-5868, pghahn@wisc.edu; John Orrock, 608-263-5134, jorrock@wisc.edu

UCLA neurophysicists have found that space-mapping neurons in the brain react differently to virtual reality than they do to real-world environments. Their findings could be significant for people who use virtual reality for gaming, military, commercial, scientific or other purposes.

"The pattern of activity in a brain region involved in spatial learning in the virtual world is completely different than when it processes activity in the real world," said Mayank Mehta, a UCLA professor of physics, neurology and neurobiology in the UCLA College and the study's senior author. ...

Single-cell phytoplankton in the ocean are responsible for roughly half of global oxygen production, despite vast tracts of the open ocean that are devoid of life-sustaining nutrients. While phytoplankton's ability to adjust their physiology to exploit limited nutrients in the open ocean has been well documented, little is understood about how variations in microbial biodiversity -- the number and variety of marine microbes - affects global ocean function.

In a paper published in PNAS on Monday November 24, scientists laid out a robust new framework based on in situ observations ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Nearly four decades of observations of Tanzanian chimpanzees has revealed that the mothers of sons are about 25 percent more social than the mothers of daughters. Boy moms were found to spend about two hours more per day with other chimpanzees than the girl moms did.

Chimpanzees have a male-dominated society in which rank is a constant struggle and females with infants might face physical violence and even infanticide. It would be safer in general to just avoid groups where aggressive males are present, yet the mothers of sons choose to do so anyway.

"It ...

A National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded research team has successfully tested an autonomous underwater vehicle, AUV, that can produce high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of Antarctic sea ice. SeaBED, as the vehicle is known, measured and mapped the underside of sea-ice floes in three areas off the Antarctic Peninsula that were previously inaccessible.

The results of the research were published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience. Scientists at the Institute of Antarctic and Marine Science (Australia), Antarctic Climate and Ecosystem Cooperative Research ...

Coral reefs persist in a balance between reef construction and reef breakdown. As corals grow, they construct the complex calcium carbonate framework that provides habitat for fish and other reef organisms. Simultaneously, bioeroders, such as parrotfish and boring marine worms, breakdown the reef structure into rubble and the sand that nourishes our beaches. For reefs to persist, rates of reef construction must exceed reef breakdown. This balance is threatened by increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which causes ocean acidification (decreasing ocean pH). Prior research ...

LIND, Wash. - In the world's driest rainfed wheat region, Washington State University researchers have identified summer fallow management practices that can make all the difference for farmers, water and soil conservation, and air quality.

Wheat growers in the Horse Heaven Hills of south-central Washington farm with an average of 6-8 inches of rain a year. Wind erosion has caused blowing dust that exceeded federal air quality standards 20 times in the past 10 years.

"Some of these events caused complete brown outs, zero visibility, closed freeways," said WSU research ...

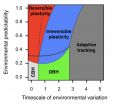

Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a model that mimics how differently adapted populations may respond to rapid climate change. Their findings demonstrate that depending on a population's adaptive strategy, even tiny changes in climate variability can create a "tipping point" that sends the population into extinction.

Carlos Botero, postdoctoral fellow with the Initiative on Biological Complexity and the Southeast Climate Science Center at NC State and assistant professor of biology at Washington State University, wanted to find out how diverse ...

Last year, University of Pennsylvania researchers Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin published a mathematical explanation for why cooperation and generosity have evolved in nature. Using the classical game theory match-up known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, they found that generous strategies were the only ones that could persist and succeed in a multi-player, iterated version of the game over the long term.

But now they've come out with a somewhat less rosy view of evolution. With a new analysis of the Prisoner's Dilemma played in a large, evolving population, they ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Nov. 24, 2014, 3 P.M.) -- Researchers at Tufts University, in collaboration with a team at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, have demonstrated a resorbable electronic implant that eliminated bacterial infection in mice by delivering heat to infected tissue when triggered by a remote wireless signal. The silk and magnesium devices then harmlessly dissolved in the test animals. The technique had previously been demonstrated only in vitro. The research is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early ...

A Jackson Laboratory research team has found that the misfolded proteins implicated in several cardiac diseases could be the result not of a mutated gene, but of mistranslations during the "editing" process of protein synthesis.

In 2006 the laboratory JAX Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Susan Ackerman, Ph.D., showed that the movement disorders in a mouse model with a mutation called sti (for "sticky," referring to the appearance of the animal's fur) were due to malformed proteins resulting from the incorporation of the wrong amino acids into proteins ...